Vaccinating Poultry as a Means of Salmonella Control

"What's so great about vaccinating poultry against Salmonella?" That was the question asked and answered at a special seminar in Thailand recently. Senior editor, Jackie Linden, reports.

Salmonella remains a problem in intensive poultry rearing, in the tropics and in free-range systems, according to Professor Paul Barrow of the School of Veterinary Medicine and Science at the University of Nottingham in the UK.

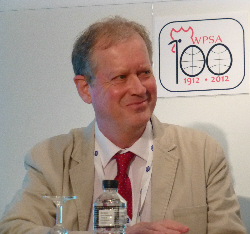

Speaking at a seminar entitled 'Poultry Science Outlook' organised by the World's Poultry Science Association (WPSA) in Bangkok earlier this year, he explained that there is a range of approaches to its control including biosecurity, antibiotics, competitive exclusion, breeding for genetic resistance and vaccination. However, tight biosecurity is difficult to achieve for outdoor systems and competitive exclusion works less well in the field than in the lab.

Antibiotics have their downsides, particularly the risk of the pathogen developing antimicrobial resistance and thus becoming less effective while also passing the resistance on to other bacteria, such as E. coli.

Genetic lines of poultry vary in their ability to resist Salmonella colonisation so this may be an approach. However, Professor Barrow suggested this would not be effective if the birds develop this level of resistance as they mature and broilers may reach market weight already by six weeks of age. If the resistance were to be achieved by genetic modification, it may not be acceptable to consumers and there is a risk that resistance to other infections and/or performance may be adversely affected.

*

"Salmonella in chickens is a gut colonisation issue."

Comparing killed and live vaccines, he said that the former stimulate high antibody titres and are more acceptable. On the other hand, live attenuated vaccines stimulate cell mediated immunity and antibodies.

Salmonella in chickens is a gut colonisation issue, Professor Barrow explained. Cell clearance is not actually related to antibodies but to T-cells. This is why live vaccines are most effective; they stimulate the T-cells.

Vaccination was traditionally possible against serovars that cause typhoid-like diseases but these may not be effective against those colonising the gut.

Professor Barrow contrasted the host-specific serovars with those causing food-borne disease. There are few host-specific serovars - fewer than 10 - and they are normally pathogenic and invasive, eliciting a strong immune response. They are host-specific and do not colonise the gut. Vaccination is feasible against the host-specific serovars.

On the other hand, there are more than 2,000 serovars of 'food-poisoning' type, he said. They vary in the degree of invasiveness in vivo and the immune response to them is poorly understood. They also tend to be epidemiologically complex as they have many hosts. They do colonise the gut well and are shed in the faeces in high numbers. These characteristics mean that the value of vaccination is questionable, according to Professor Barrow.

However, it may be possible to get cross-protection between similar strains, he said, and GM live Salmonella vaccine development looks promising.

Professor Barrow outlined eight criteria for an ideal vaccine:

- strong protection against both faecal excretion and systemic infection (chicks and ovarian)

- stable avirulence in Man

- avirulent for chickens, without adversely impacting growth rate

- long-lasting protection

- protection against many serotypes

- easily administered

- easy to differentiate from the field strain by culture or serology, and

- compatible with other control measures.

Vaccines are in use in poultry in the European Union and elsewhere and lab reports show a decline in food-borne disease since the 1990s, which is likely at least partly attributable to vaccination.

In the EU, the authorities are monitoring Salmonella on farms and taking steps to deal with positive breeding flocks.

Since 2004, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has discouraged the use of antibiotics for the control of food-borne pathogens in farm animals.

Vaccination alone will not be completely effective; thorough cleaning and disinfection are also required, Professor Barrow said, adding that the vaccine does have a withdrawal period.

He showed that vaccination status has been shown to be the number 1 factor associated with Salmonella Enteritidis on hen holdings in Europe.

Several vaccines are available on the market - both live and inactivated types - and they vary in efficacy, Professor Barrow concluded.

June 2013