Reducing the Environmental Impact of Turkey Production

Nearly three years in development, the UK’s University of Newcastle and Cranfield University and industry partners have introduced a new tool firstly to assess and then to improve the environmental impact of turkey production, reports Jackie Linden.The new tool, which works on Microsoft Excel, can calculate the environmental impacts, including the carbon footprint, of turkey production per kilo of liveweight or per kilo of carcass for any system using data entered by the user. So the results are tailored to the particular farm conditions – for example, management, feed and fuel used.

Dr Illka Leinonen of Newcastle University, one of the developers of the tool, explained that, having generated the data for their current system, the user can make changes to see what the effect might be on the carbon footprint of actual or hypothetical changes – the “what if” scenario.

What the new tool cannot do, he said, is to predict bird performance, fuel or energy use or generate average figures for the sector, for example.

Industry Involvement

Background to the project, explained Jeremy Hall of Bernard Matthews, is growing consumer interest in climate change and the pressing need to be able to calculate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for the production of all farm animals.

Bernard Matthews was one of the partners in the project, which was funded by Innovate UK and also included Cranberry Foods, Kelly Bronze Turkeys, Aviagen, DSM, Evonik, AB Agri, the British Poultry Council and the two UK universities.

The work follows on from previous projects by the Department for Agriculture (Defra), calculating the environmental impacts of egg and broiler production.

The British turkey sector was keen to be able to promote its green credentials in comparison to other meats and to do that, it needed up-to-date comparative data to be able to tell consumers that eating turkey would not harm the planet.

Mr Hall said: “Consumers need to confident that in choosing turkey meat, they are having less environmental impact than other meats.”

He added that the three-year project, collecting data over two winters and two summers with experts at two eminent universities, has resulted in helpful constructive and thought-provoking findings.

What Can a Life Cycle Analysis Achieve?

Coordinator of the scientific part of the project was Professor Ilias Kyriazakis of Newcastle University who explained that the project had three main aims. These were to quantify the current environmental impact, identify any “hot spots” and to investigate the effects of any system changes.

It can also be used to identify opportunities to improve environmental performance and ask those “what if” questions.

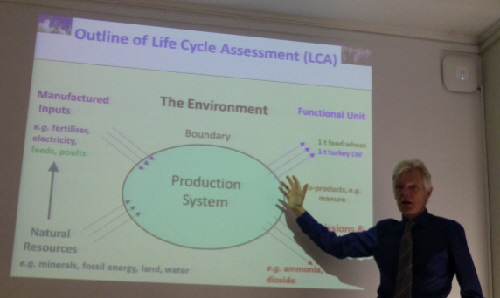

Their approach to this Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) was to cover the whole production chain from raw materials to final product, be that live bird at the farm gate or eviscerated carcass at the processing plant.

How the LCA is Developed

An LCA is developed in four stages, explained Dr Adrian Williams of Cranfield University.

The first is to compile the data for all the activities in the whole process – in this case, turkey production to the farm gate.

Technical co-efficients are then applied to each activity to calculate the environmental impacts for each one in terms of primary energy (PE) use, global warming potential (GWP), eutrophication potential (EP) and acidification potential (AP).

Next, the total for each measure is aggregated to form a sum of the emissions to calculate the impacts per functional unit, in this case per kilo of turkey liveweight or per kilo of eviscerated carcass.

The final stage is to scrutinise the data, which involved checking its quality and assessing if there are statistically significant differences.

LCA Findings

Year-round turkey production

The first results from the LCA calculation presented by Dr Leinonen compared males (stags) and females (hens) and rearing in controlled-ventilation houses or on free range for the year-round, standard turkey market.

PE use and GWP are largely governed by feed use. The stags had slightly higher values than the hens but as there was variation within each group, the differences were not statistically significant.

Manure and bedding was the main contributor to AP and EP. Again, there was a trend for the figures to be slightly higher for the stags than hens.

Christmas turkey production

Traditional farm fresh (TFF) turkey production is a very different market as it provides birds just once a year, for Christmas.

Smaller in overall output than year-round production, there is a good deal of variation in production systems, including wide use of organic feeds.

Again, feed was the factor most influencing PE use and GWP and those systems using organic feed tended to have higher figures than those based on non-organic feed.

The TTF system using non-organic feed produced similar environmental impacts in terms of PE use and GWP to standard production on the basis of unit liveweight.

Effects of Mitigation Strategies on LCA

The project team has already used the model to investigate a number of strategies to mitigate the environmental impacts of turkey production, as Dr Leinonen explained.

In summary, he said, one that shows great promise is to use poultry litter to generate electricity rather than use it as a fertiliser.

Other changes, such as using alternative proteins in the feed, reducing stocking density or increasing slaughter age made relatively small differences to the environmental impact measures.

Replacement of soybean meal in feeds

Heavy dependence on soybean meal in animal feeds in Europe and elsewhere is one of the main reasons for the strong influence of feed-related factors in the environmental impact measures. The Land Use Change element is particularly high for soybean meal, nearly all of which has to be imported, mostly from South America.

This has encouraged the search for alternative proteins and one such trial was conducted by Bernard Matthews, replacing soybean meal with a combination of field beans, rapeseed meal and sunflower meal.

Contrary to expectations, Dr Leinonen showed that there were no significant differences between the two dietary treatments in terms of environmental impact.

In practice, other ingredients needed to be added to the ‘alternative’ diet to achieve the required specifications, the crude protein level was higher for each phase and the birds performed slightly less well than with the soybean meal diet.

Adjusting stocking density

Another trial at Bernard Matthews compared the effects of different stocking densities over three cycles.

The differences between the groups were not statistically significant but the lowest stocking density tended to have more environmental impact overall – in terms of PE use and GWP – because there were fewer birds in the house.

Slaughter age effects

For this work, the team calculated the effects using the model, based on performance figures and actual data from Bernard Matthews for electricity, gas, water, bedding and feed intake, Dr Leinonen explained.

Comparing slaughter ages of 16, 18 and 20 weeks, there was a trend for all four environmental measures to increase with the age of bird at slaughter. This would be expected as the bird’s feed conversion deteriorates with age.

However, when expressed per kilo of carcass weight, rather than liveweight, the trends were less pronounced.

Manure as fuel rather than fertiliser

Dr Williams explained his latest work comparing the environmental impacts of poultry litter used as a fertiliser compared to its use as a substrate for power (electricity) generation.

With information on the turkey manure again provided by Bernard Matthews and some data from the power sector, provisional results shows considerable advantages in terms of AP and EP in favour of burning the litter for power generation. This he attributed to the reduction in ammonia, which has marked deleterious environmental impacts. There was also a clear but smaller beneficial effect on PE use.

Mr Hall commented that, at Bernard Matthews, they have 21 houses already obtaining all their heat from boilers burning wood pellets. If biosecurity risks can be overcome, he said, the company would be keen to consider switching to poultry litter as a substrate as well as to investigate drying and pelleting the manure so it could be used to generate power off the farm.

November 2014