How Do Wild Birds Spread Avian Flu?

Low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) is a problem in the poultry industry, and has the potential to evolve into highly pathogenic versions of the disease (HPAI). A scientific report from various scientific institutions in North America recently looked at the infection patterns of LPAI and how it relates to wild bird migration pathways.LPAI is thought to be spread primarily by wild birds, especially waterfowl of the order Anseriformes, which acts as a natural reservoir of the virus. A US Department of Agriculture (USDA) report looking into the recent cases in the US said that wild birds were most likely responsible for introducing avian flu into commercial poultry.

Many countries have conducted surveillance operations looking at wild birds, aimed at early detection of LPAI viruses. However, none of these studies have looked at the large scale patterns of transmission of LPAI, or analysed the ecological conditions in which infection occurs.

The new study, entitled 'Demographic and Spatiotemporal Patterns of Avian Influenza Infection at the Continental Scale, and in Relation to Annual Life Cycle of a Migratory Host', and published in PLOS One, set out to do just that.

The scientists used data from blue-winged teal (Anas discors) birds, sampled across the United States and Canada over a four-year period. According to their report, this species is an ideal model for studying the transmission of LPAI, as this highly gregarious bird has a large migratory range, and is frequently infected with LPAI.

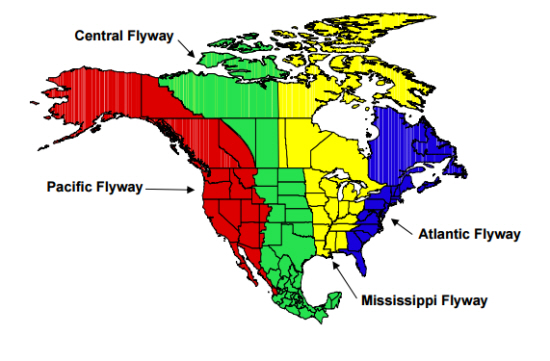

The researchers examined the effects of year, season (as defined by stage of annual cycle of the host), flyway, latitude, and demographic factors (age and sex) on the probability of avian flu infection in the birds.

They expected the effect of season on infection rates to be large, as the birds congregate in large groups just prior to the autumn migration south, and this can lead to high transmission rates both orally and through faecal matter. However, the effects of this aggregation was expected to be smaller as the birds grew older (more than one year old), as they developed greater immunity against the virus.

The scientists also tested whether migratory pathways ('flyways') with greater densities of birds would show greater infection rates, and whether one sex was more susceptible to the disease than the other.

In the best computer model of infection rates that the scientists could extract from the data, their expectations were largely supported.

Birds in their hatch year (less than one year old) were more likely to test positive for avian influenza in the summer, just before the annual migration in the autumn, compared with birds over one year old. However, the difference decreased as the year went on, and there was no difference between birds of different ages in the November to June period, comprising the winter, spring migration, and breeding seasons.

This result was similar to findings in mallards, which showed that juveniles of the species were the biggest drivers for seasonal disease outbreaks.

Male blue-winged teal were 23 per cent more likely to become infected with the disease than females, and different years had different infection rates. The migratory bird flyways across the US (Atlantic, Central, Mississippi and Pacific) also had different infection rates.

In addition, the probability a blue-winged teal was infected with avian influenza increased with latitude up to 48 degrees north, after which there was no further increase in infection risk with latitude. The authors explained that colder weather is thought to preserve flu viruses better, allowing them to persist in the environment, whilst extreme cold is thought to decrease their survival.

The authors of the study say that these results enhance scientific knowledge of how LPAI spreads, and can be used to direct avian flu surveillance operations in future, by identifying the key windows of time and space critical for transmission.

This should help governments to detect outbreaks of LPAI in wild birds sooner, which is especially important given the recent devastation caused by avian flu in the US' poultry industry.