Making Money from Poultry Litter as Fertiliser

Poultry manure can be a great source of fertiliser, and could make poultry farmers some extra money if used well, writes Byron Stein, Editor of the 'Drumstick' newsletter from the New South Wales Department of Primary Industries.Spent poultry litter is great stuff… if you are growing pasture, crops, veggies and just like your garden looking great.

Yet to many poultry producers, getting rid of spent litter continues to be a cost to their business rather than a nice little side earner. So why is this?

This article explores some of the key findings of a new Australian Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC) report ‘Chicken litter: alternative fertiliser for pastures and ways to increase soil organic carbon’ and will highlight some of the key benefits and limitations of using chicken litter as a fertiliser source for pastures.

Nuts and bolts

- Broadcasting litter onto pastures can give similar pasture growth responses to conventional inorganic fertilisers such as superphosphate and urea.

- Capital rates of litter and conventional fertiliser both increased energy and protein levels in pasture by similar amounts.

- Nutrient values in litter can vary hugely from batch to batch.

- Transport costs are one of the key factors in limiting wide spread use of litter by graziers. As a rule of thumb, chicken litter is cost competitive with conventional inorganic fertilisers within approximately 100km from the chicken farm. Cost competitiveness also depends on current conventional fertiliser prices.

- Whilst litter contains a range of key nutrients like Nitrogen (N), Phosphorus (P) and Potassium (K), litter also contains useful trace elements and carbon. Unfortunately it’s difficult to value these additional benefits into the pricing of litter.

- The cost competitiveness of litter depends on current inorganic fertiliser prices. At current superphosphate prices, $16/m3 of litter spread represents good value for a single nutrient like phosphorus (on a $/kg basis) compared to conventional fertilisers. Litter prices above this value are not likely to be competitive at current inorganic fertiliser prices.

Poultry producers wishing to sell litter as a fertiliser need to consider current conventional inorganic fertiliser costs, and price their litter accordingly.

What the report is about

The RIRDC report summarises the results of three years of litter applications on pasture yields and soil nutrient and carbon levels and compared these to applications of conventional inorganic fertilisers.

The report also showed the impact of litter applications on pasture species, feed quality, plant leaf tissue and soil microbial activity.

What did the researchers do?

The trial was conducted at two sites in Victoria with different soil types. Fresh (non-composted), single batch litter chicken litter was applied at three different rates and was compared to applications of conventional inorganic fertilisers with the same nutrient values as the litter applications.

Litter and fertiliser products were applied each year from 2009-2012. Data was collected on:

- pasture production (kg DM/ha);

- species composition;

- pasture feed quality;

- topsoil macro nutrient (N,P,K,S) levels, trace elements/heavy metals, pH, salt, cations;

- topsoil and subsoil carbon content, carbon stocks and carbon fractions;

- leaf tissue macro nutrient and trace elements levels;

- soil microbial activity and microbial biomass organic carbon.

The application rate of both the litter and the conventional fertilisers was based on the nutrients in the litter from each batch, and included maintenance (8.4 kg/ha) and capital (16.8 kg/ha) application rates for phosphorus (P).

What did the researchers find?

Litter composition

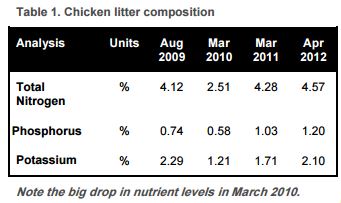

Nutrient content for single batch litter from the same farm varied significantly from batch to batch, as shown in Table 1.

Phosphorus levels were shown to vary by as much as 100 per cent, with the lowest recorded level at 0.58 per cent while the highest level was 1.2 per cent

Cost of nutrients - comparison with conventional fertiliser

In the trial, litter was costed at $20/m3 (cubic metre) delivered and $28/m3 spread. At this price, on an individual nutrient basis, litter was always more expensive than conventional fertilisers.

Where more than one nutrient is required, however, litter can become cost-effective. Litter would have to be approximately $16/m3 delivered (half the price) to supply a key nutrient like P at a similar cost to superphosphate (at $400/t).

This is probably one of the key things to consider when valuing poultry litter as a fertiliser, especially when you only need one or two key nutrients, for example phosphorus or nitrogen.

Clearly, as superphosphate (super) or urea become more expensive, as has happened in the past, poultry litter becomes very cost competitive.

However, the reverse is also true. When super and urea get cheaper, poultry litter struggles to compete on a cost per nutrient basis, depending on the cost of litter (spread).

Changes in soil fertility

Soil nutrient levels rose by similar amounts when comparing conventional fertiliser applications with litter.

Maintenance rates of inorganic fertiliser increased P levels by 4-6 units compared with the Controls, whereas the Capital rates increased P levels by 7-9 units.

The Maintenance and Capital rates of litter increased soil P levels by a similar magnitude as their equivalent rate of inorganic P fertiliser.

Trace elements

Chicken litter is also a valuable source of the trace elements copper, zinc and molybdenum, which can be deficient in certain soil types. Copper and zinc levels in soil increased with increased rates of litter at both sites.

There were no significant effects on soil iron or manganese content. Plant tissue levels of copper and molybdenum also increased with increased rates of litter.

Pasture responses

The research showed that broadcasting chicken litter onto pastures can give similar pasture yield responses to conventional, inorganic fertilisers. However it should be noted that the pasture yield responses observed in this research were mainly due to nitrogen.

For soils with adequate phosphorus levels it is more cost-effective to apply nitrogen (urea) alone rather than litter, in the short-term.

Soil carbon

Multiple applications of poultry litter were shown to increase soil carbon levels. Soil carbon is becoming an increasingly hot topic for environmentalists as well as farmers.

Soil carbon has been shown to increase the overall health of soils, stimulate microbial activity and increase water retention capacity of soils.

However, this trial failed to demonstrate pasture yield responses from increased soil carbon over and above that of conventional fertilisers.

The reason for this is time. The trial only lasted three years and this is not nearly enough to demonstrate the potential improvements in pasture yields associated with increased soil carbon.

Poultry litter is a long term prospect, and real value associated with litter applications is likely to take five or more years to show results. This is a valuable message.

Poultry litter users should think of litter as long term investment for selected paddocks and crops, and may need to supplement litter applications with inorganic fertilisers for short term results, depending on soil test results and pasture or crop requirements.

What does this all mean?

The ‘Chicken litter: alternative fertiliser for pastures and ways to increase soil organic carbon’ report showed that poultry litter can be just as effective at increasing soil nutrient levels and pasture production as conventional fertilisers.

However, the cost competitiveness of litter very much depends on transport distance, current conventional fertiliser prices and the particular soil nutrient requirements of the paddock or farm being fertilised.

Growers and spent litter suppliers need to take all of these things into consideration and price their spent litter accordingly to make sure they are offering a good deal to make their spent litter attractive to potential clients.

For growers in the Sydney basin or other metropolitan regions greater than 100km from pasture and cropping areas, getting a return on spent litter is more challenging because of the transport costs involved.

For these growers, composting litter or entering into contracts with litter suppliers or merchants may be their best alternatives. These growers however should ensure that they are still getting a fair deal for the litter they are supplying.

Finally, spent litter may become a more attractive product for niche organic markets or clients that are seeking to increase their soil nutrient and carbon levels.

Unfortunately, the carbon in litter is difficult to cost, and the benefits of increasing soil carbon are usually only realised in the long term. Despite this though there is likely to be a growing niche market of small scale and hobby farmers who may be attracted to the multiple benefits that spent litter offers.

The ‘Chicken litter: alternative fertiliser for pastures and ways to increase soil organic carbon’ project was funded by the Chicken Meat Program within the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC).