US Pork, Poultry Producers Still on Look Out for Deadly Diseases

US - As autumn begins, the US meat and poultry sector once again watches carefully for signs of disease and contemplates its impact, write Steve Meyer and Len Steiner.The difference, of course, this year is that the sector is watching for two potentially game-changing diseases - porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus and high-pathogenic avian influenza.

Both diseases have been relatively quiet - as would be expected for viruses that do not survive as well outside of a host animal in warm weather - but could certainly become more active as temperatures cool.

Let’s recap the status of the two diseases, their impacts and the prospects for the fall and winter.

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDv) had a devastating impact on piglet survival rates in the wither of 2013-14 but was not nearly as severe in either prevalence of impact last winter.

Immunities in herds that were exposed that first winter plus MUCH IMPROVED biosecurity practices were both factors in the reduced frequency of PEDv last year.

Part of the concern for the coming winter is that immunity levels. Producers and their veterinarians know that those will be lower due to both the natural tendency for antibody levels to decline after exposure to a virus and the fact that a good number of the sows that went through the large number of 2013-2014 breaks have now been culled.

Many systems have continued to expose replacement gilts to the virus before they enter sow herds but it is thought that even that practice will not duplicate the virus?combating abilities that the collective national sow herd had after that first winter of PEDv cases.

The other factor - management - remains a deterrent going forward. Producers and veterinarians know much more about how to control the virus, keep in on the farms where it appears and keep it out of farms where it has not been detected.

The question for the coming winter is intensity. It’s a Catch?22 situation: Intense management is needed to prevent the virus from becoming a problem but without the virus as a problems can managers ratchet up the intensity of prevention efforts?

There is little doubt that the efforts will be better than in that first winter but without the fresh memories of thousands of dead baby pigs, can it be raised to the intensity that contributed greatly to last year’s reduction in total case numbers and, more importantly, the big reduction in the number of sow farms that broke with PEDv?

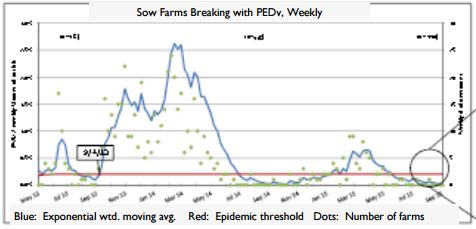

That reduction is clear in the graph from the University of Minnesota’s Swine Health Monitoring Project.

PEDv cases began to pop up in early November last year and we would expect a similar time line this year. High-pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) is a bit more of a mystery in that we are still not through our first year of dealing with it first hand.

The virus first appeared in the US last December in the Pacific Northwest. It popped up in Minnesota, Missouri and Arkansas almost simultaneously this past spring suggesting that migratory birds were the likely vector of transmission in the early going.

Human and vehicle movement took over from there and helped spread the disease to a large number of commercial turkey and layer facilities in the Midwest with Iowa and Minnesota particularly hard hit.

There have to date been a total of 223 cases impacting 48.091 million birds, roughly 38 million of those being layers. Importantly, there has not been a case since June 17, more than 90 days ago.

That means that most countries that have banned US poultry products could lift those bans. We have heard of no such action yet and we suppose that concern over the spread of the virus this fall is one reason for those delays.

If migratory birds were indeed a primary vector, the concern this fall is that those birds that moved up the Mississippi Flyway last spring could have shared the virus with their Atlantic Flyway cousins during the big reunion in Canada, now to have those cousins bring the virus to key broiler areas in eastern and southeastern states.

No commercial broiler operations have been impacted by HPAI to date! All of the export bans (nine country-wide bans, 31 state-by-state bans, 18 county-by-county bans - all according to the USA Poultry and Egg Council) were based on cases in layers and turkeys.

The only major broiler state that has been impacted so far is third-ranked Arkansas. The Atlantic Flyway touches major production areas in the DelMarVa, Georgia (#1), Alabama (#2) and North Carolina (#4).

HPAI cases in those states would almost certainly add them to the state export ban lists for most countries. But HPAI would also reduce chicken numbers and thus restrict supplies.

Which impact would win if domestic dark meat supplies grow but white meat supplies are reduced, perhaps significantly? The US is a white meat market and dark meat prices are already very, very low.