Economic Organization of US Broiler Production

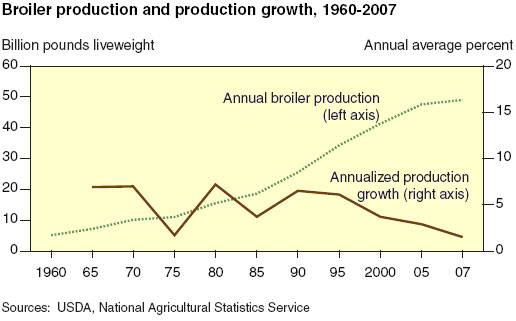

U.S. consumption of chicken averaged 86 pounds per person in 2006, more than triple the 1960 level, writes James MacDonald in a USDA Economic Research Service, Report Summary.Chicken became a preferred option as incomes increased and chicken prices remained inexpensive compared with other meats, and as processors created new chicken products that appealed to consumer tastes. Increased consumption required increased production of broilers, which the industry accomplished through a tightly integrated production system that links chicken companies, called integrators, with independent broiler growers through production contracts. The industry’s distinctive organization has contributed to its commercial success, but it now faces a series of challenges.

What Is the Issue?

After decades of rapid expansion, growth in both broiler production and productivity began to slow in the mid-1990s. Slowing growth creates challenges for industry decision makers, as they consider how to encourage further investments in capacity and new technology, and attempt to manage existing and aging production networks.

The broiler industry plays an important role in several public policy issues:

- Large animal feeding operations, including those raising broilers, are under increasingly strict environmental regulation by all levels of government; and

- The broiler industry has dealt with poultry diseases and associated biosecurity issues for many years, while growing public awareness of such threats plays an increasingly important role in industry and public policy planning.

What Did the Study Find?

Other industries use production contracts, but the broiler industry is distinguished by the dominance of such contracts and the methods by which growers are paid. Almost all broiler growers’ contracts base the compensation on how each grower’s performance compares with that of others.

Beyond that feature, however, contracts are far from uniform. Contracts can include other terms that tie base payments to actions that affect grower costs or that assign some expense or revenue categories to either the grower or the integrator. Contracts also cover a wide range of specified durations, from just over a month to 15 years. Variations in contract design likely follow from differences in grower location, size, and type of broiler housing, but the wide variation in terms and payments makes it difficult for growers to evaluate contracts.

The industry’s organization has contributed to its commercial success. High rates of productivity growth, along with new product innovation, led to high growth rates for chicken production, domestic consumption, and exports. Growth in production slowed noticeably, however, after the mid-1990s. With slower production growth, investment in new housing also slowed. New housing embodies new technology, so slowing investment can hinder future productivity growth, unless older houses can be effectively retrofitted with newer equipment. Integrators are requiring such retrofitting for some operations as a condition of extending their contract. For newer and larger operations, integrators are offering contracts of longer duration to induce them to continue to invest in new technology.

Broiler production is gradually shifting to larger operations, a trend common to most agricultural commodities. For operators of small broiler enterprises, off-farm income is the primary source of the household’s income, and the broiler enterprise provides a modest amount of additional income. For larger operations, the broiler enterprise typically is the primary source of the household’s income. As a result, operators of larger enterprises may be more sensitive to the income risks arising from energy price fluctuations and contract settlements. Contract features may need to be redesigned to adjust for differing risk exposures faced by growers.

Larger operations may realize scale economies in production, but they also concentrate poultry litter in localized areas. Litter is bedding material, such as wood shavings, sawdust, or straw, that is spread on the floors of broiler houses. When it is removed, it consists mostly of poultry manure, along with the original bedding, feathers, and spilled feed. In 2006, about 40 percent of used litter was spread on the farm’s fields, while the rest was removed from broiler operations for field application elsewhere or for processing. There was enough of a market for litter in 2006 to allow growers to sell about a third of the litter removed from farms, but farmers had to give away the rest or pay to have it removed. Litter disposal remains a major issue confronting the industry.

How Was the Study Conducted?

The analysis relies on data drawn from a large-scale representative survey of producers, conducted as part of the annual Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS), which is the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s primary source of information on the financial condition of farm businesses and households and farm production practices.

Two ARMS versions collect financial and production information for all types of farms, but other versions target specific commodities and collect additional information on production practices, financial performance, and contractual relationships for those commodity enterprises. ARMS included a broiler version for the first time in the survey conducted early in 2007, with a focus on performance during 2006. The survey’s target population consisted of all operations that produced broilers for meat and had at least 1,000 broilers on-site at any time during 2006 in the 17 States that accounted for 94 percent of U.S. broiler production. Analyses in this report are based on responses received from 1,568 operations, out of 2,100 originally selected for the survey.

Further Reading

| - | You can view the full report by clicking here. |

June 2008