Understanding how the infectious bronchitis (IB) virus attacks the chicken’s respiratory system clarifies why broad IB vaccine protection is needed, said Aris Malo, DVM, global technical director for poultry, MSD Animal Health.

IB, a highly contagious and widespread disease, has become a major economic concern to the poultry industry worldwide, causing urogenital as well as respiratory problems, he said.

In layers and breeders, it leads to reduced egg production and poor egg quality; in broilers, it causes poor performance; and in all affected chickens, it predisposes to secondary infections, resulting in higher mortality and an increased use of antibiotics, Malo explained with the aid of a colorful, animated video.

IMMUNE RESPONSE

The IB virus, which is spread by the inhalation of droplets, has a number of characteristic spikes on its surface. The spikes are proteins that play an important role in the onset of infection and the corresponding immune response, he said.

After entering the bird’s body, the IB virus quickly reaches its primary targets — the trachea and bronchi. Birds with immunity to the virus have protective barriers, which consist of the cilia — the hair-like structures lining the respiratory tract — and mucus produced by goblet cells. Together they form a self-cleaning mechanism that provides protection against a variety of invading pathogens, Malo continued.

In unprotected birds, however, the IB virus is able to overcome the protective mechanism. The virus binds to cells on the surface of the trachea. To do this, it uses its protein spikes to attach itself to receptors on the cell membrane (Figure 1). Next, the virus pushes itself into the cell interior, where it multiplies and infects other cells, in turn producing more viruses and causing the cells to lose their cilia (Figure 2).

“In this way, the natural barrier against invading pathogens is progressively destroyed, but if the binding of IB virus to cells can be prevented, infection will not occur,” he said.

INITIATING IMMUNITY

Vaccination can prevent binding by initiating a prompt immune response based on local mucosal immunity, the veterinarian explained. Antibodies to the IB virus are produced and bind to the protein spikes on the IB virus; the spikes are no longer free to attach themselves to receptors on the cell membrane, thus preventing IB infection (Figure 3).

“Unfortunately, it gets a bit more complicated,” he said. There are many variants of the IB virus with different surface proteins or spikes; protection induced against one type may not always be efficacious against other types.

“That’s why, despite vaccination, birds can still break with IB — if the IB virus that attacks is different from the IB vaccine used,” he said.

On the other hand, it is possible that some IB serotypes induce immunity against more than one serotype because even though they have different surface proteins or spikes, they share some similarities. In that case, such an IB serotype is called a Protectotype, Malo said.

An example of Protectotype is Nobilis IB Ma5 vaccine, based on the Massachusetts serotype, which leads to broad protection, he said.

Even better protection is achieved if an additional IB serotype is used for vaccination. An example would be Nobilis IB 4/91, which is based on the 4/91 variant that is widespread throughout Europe.

“The use of Ma5 administered on day 1, followed by 4/91 on day 14, has been found to be especially effective and will protect the birds against most IB viruses during the first weeks of their lives,” Malo said.

To safeguard egg production in long-lived layers and breeders, repeat vaccinations before the onset of lay is needed and should include the use of an inactivated, multivalent IB vaccine, he advised.

PROOF OF EFFICACY

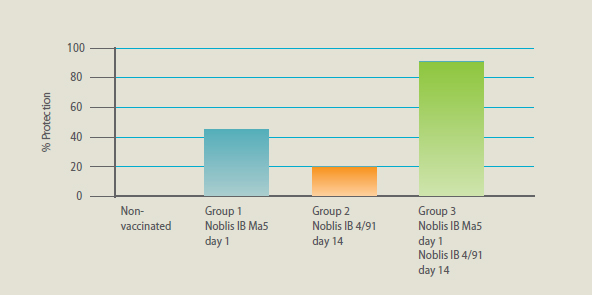

The efficacy of these two vaccines has been widely proven using the ciliostasis test, a tool that measures the impact of a virus on the cilia of the trachea. For the test, veterinarians or technicians take samples from different areas of the trachea so ciliary activity can be measured. The ciliostasis test also evaluates the level of protection after vaccination, Malo said.

Values above 50% represent good ciliary activity and, therefore, good protection. Values below indicate insufficient protection. Studies show that the use of both Ma5 and 4/91 yields far better results than using each vaccine individually, he said (Figure 4).

The vaccines can help the poultry industry avoid the considerable financial losses associated with IB infection, Malo concluded.

More Issues