Gains Across Product Range 'Lock in' Cobb Trade Mark Advantages

In this interview with Roger Ranson, Dr John Hardiman, Cobb vice president – research and development for the past 24 years, talks about genetic progress with Cobb products and about the impact genomics is beginning to make. It is published in the latest issue of Cobb Focus.

John, let’s start looking at the individual breeds. During your time with the company, the Cobb500 has become the world’s top selling single broiler breeder. Why do you think it’s become so successful?

Genetically, I think that part of this success can be attributed to our concentration on improving efficiency and bird uniformity in a modern high yielding broiler. For example, today’s Cobb broiler is 0.40 better in feed conversion, two pounds (0.9kg) heavier at the same age and six per cent higher in breast meat yield than just 20 years ago. But without continued investment in our Cobb research and production facilities, and without our technical and sales support, this success wouldn’t have been possible.

Customers see the results of your work many years after you’ve made decisions about breeding? So what are the gains they’ll be seeing over the next few years?

I believe that over the next decade, our customers will see improvements in both economic and welfare traits. Over the next five years, the Cobb500 will improve in egg production, hatchability, bodyweight, breast meat yield, feed conversion and liveability – up to five eggs more, one per cent hatch, half a pound (230g) in weight, two per cent yield, 0.15 feed conversion and one per cent livability. Our customers will see similar improvements in our other Cobb products to a greater or lesser degree.

We have maintained good genetic variation for each of these traits in our pedigree lines, and new selection technologies will allow us to select more accurately and make faster progress in improving the core pedigree as well as new experimental lines. Our goal has always been to be the leader in new selection technology and we develop a new selection tool about every two years. But we wouldn’t advertise all our new selection technologies given the need to protect some of our research advances.

* "Our goal has always been to be the leader in new selection technology and we develop a new selection tool about every two years." |

|

|

We used to think that the Cobb500 was the breed for all markets, but more recently we’ve seen the Cobb portfolio widen and new lines introduced. How much of the world market will continue to look toward the Cobb500 in the years ahead?

Distinct segments have emerged in the world market as companies provide different products for their valued customers and as demand increases for products like further processed, convenience food. We recognise about four segments with the largest focused on cost and efficiency, brought about in large part by good feed conversion. This segment is well served by the Cobb500 and is still a majority of the total market. The move to high yield, deboned products is predicted to progress slowly, adding to the high yield segment, while more developing markets want better broiler and cost performance which is adding to the efficiency segment and potential Cobb500 sales.

The major launch in recent years has been the Cobb700 with its higher meat yield. How different is this product from the Cobb500 today?

The Cobb700 was developed to help meet the needs of the large bird/high yield market where very high deboned breast meat yields are critical. The Cobb700 will produce at least one per cent higher yields than the already high yielding Cobb500 and with similar feed conversion. The Cobb700 grows slightly more slowly which helps liveability at higher weights. It lays fewer eggs than the Cobb500 but this difference is more than compensated by the additional breast meat.

What improvements can we expect to see in the Cobb700 over the next few years?

The major difference in genetic performance will be in breast meat yield which will increase the difference between the Cobb500 and the Cobb700 to two per cent or more. Broiler liveability should also improve by about one per cent while egg production in the parent will continue to increase by almost an egg per year.

Then there is the CobbAvian48 where a balance between good breeder and competitive broiler performance brings benefits for the live, whole bird and parts market. How are you developing this breed to capture perhaps a bigger market share?

Genetic improvements in the CobbAvian48 will essentially be identical to those of the Cobb500 with the exception of egg production and breast meat yield. Over the next five years, egg production in the CobbAvian48 will improve by slightly more than five eggs, with breast meat yield improving.....about 1.5 per cent higher. The emphasis therefore is on producing a very competitive broiler with higher egg production and chick numbers that the Cobb500.

We’re looking to overall five-year genetic improvements similar to Cobb500 – at about 15 points on feed conversion, with weight goals and feed conversion improvements nearly identical. If you’re using CobbAvian48 and worried it won’t keep pace with the Cobb500, that won’t be the case. All these programmes lock in the Cobb ‘trade mark’ of good growth and great feed conversion, then we put more selection pressure on either the eggs or yield. Our customers wouldn’t tolerate anything else!

Recently, we’ve seen the marketing of a joint specialty product with Sasso and the acquisition of the Kabir lines. What have you discovered to date and will Cobb be devoting more resources to this work in the future?

Our business partnership with Sasso has allowed us to develop and offer a ‘point of difference’ chicken for customers desiring a slightly s lower growing, higher livability broiler with some colored plumage. Yes, we’re excited about the prospects of developing additional new products with Sasso to cover an even wider range of slower growing, colored products for sale in Europe and internationally.

In fact, the lines that Cobb acquired during the purchase of Hybro and Kabir have added 20 coloured lines for developing alternative products in the future.

We are conducting research with disease resistance on several of these coloured lines and have every belief we’ll find lines and eventually genes or gene markers related to improved disease resistance.

How easily could you transfer these genes to one of your mainstream products?

If we’re able to identify gene markers associated with these livability traits, then introducing – or the technical term is ‘introgressing’ – them into other Cobb lines will not be difficult. If we find there’s a particular coloured line that’s very resistant to disease ‘x’, we will attempt to genotype those birds and then find out what gene markers are associated with that resistance. That is no simple task – it will take three to five years to find the marker – but once you have this you can cross lines naturally and select for animals which are like the original line but have the disease resistance gene markers. Back crossing to say the Cobb500 line over and over again, it becomes 99 per cent Cobb500 but with the new gene – a completely natural process that’ll take about eight or nine years.

Can we turn to wider issues and first to the joint genomics research program involving the US Department of Agriculture, Hendrix Genetics and several leading academic institutions. This has been running for well over a year, so how much progress can we report at this stage?

This genome wide selection program, partly funded by the USDA, has given Cobb and Hendrix Genetics an unprecedented opportunity to test the use of large numbers of gene markers in poultry selection. This work required developing a unique 60K SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) chip. Both Cobb and Hendrix Genetics are carrying out experimental selection using this technology in several commercial lines and we’re now analysing the first generation of results. We expect increased selection accuracy and therefore faster genetic progress for our customers.

Have you been surprised by any of the findings so far?

Yes, our preliminary research results indicate that we can select for typically poorly heritable welfare-related traits such as leg defects more effectively using these methods.

We know that any single nucleotide change in the DNA could be important and in our research we started with half a million SNPs and began to study these within each of our lines to find the ones that had differences. We then applied a series of tests to find if these differences were good polymorphisms to include in the new chip, and within a few years you begin forming associations with different traits.

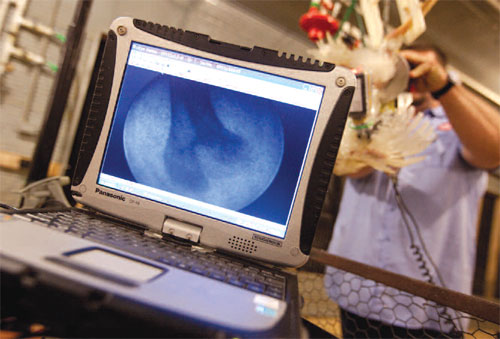

The process involves taking a blood sample just like we do for normal health testing – red blood cells are full of DNA – you extract the DNA, multiply that DNA through a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) process and place that DNA on the chip where it can be properly read and the data are sent back to computer files. You need to have a special reader that will indicate which of those SNP markers the animal is positive for. All this requires a very complex series of computer programs to data-mine this information and find associations between potential markers because genes rarely act alone, they act in concert with other genes.

When will the market be likely to see the benefits of the investment in this joint research?

The members of this research consortium are working hard to keep up with the theoretical, computational and analytical requirements of this new selection method. Continuing to develop programmes to interpret and analyse this huge volume of data will likely take two to three more years. In addition, the costs of processing or genotyping each animal is still very high and these costs will need to be reduced, and the number of gene markers actually used to test each animal simplified, to make this technology practical in the near future.

The cost of testing can be as much as $150 an animal. Just compare that to the cost of a day-old chicken! However we’ve good reason to believe that each year, the cost of genotyping animals will decline through improvements in automation and technique. So we think the cost will come down to the point where we can test reasonably large portions of our lines. I don’t know if we’d do every bird but we’ll be able to budget for increasing this testing every year which will make it more and more accurate. The system has a wonderful feedback mechanism too – the more you do, the more you learn. In fact, we never stop phenotyping and measuring, and we’re constantly checking ourselves and constantly learning new things. Lowering the cost of genotyping will be the secret... as well as not abandoning the old phenotyping, but combining it with the new genotyping.

February 2010