Administration of inactivated vaccines to laying hens

1. Introduction

The world of poultry production is subject to a system of constant change in order to adapt to consumer requirements at farm level. These requirements have brought about improvements in terms of genetics, infrastructure, management, nutrition, and immunology. Nevertheless, over the last few years, adaptation of the modus operandi of farms to meet these consumer demands has brought with it the risk of compromising the viability of the birds if a series of important variables are not considered.

At the present time, it is common to find batches with a longevity that would have been unimaginable 5 years ago, in some cases reaching 100-120 weeks, or multi-age farms where there are up to 5 or 6 different ages of birds and high densities in order to maximise the profitability of the space. All these changes increase the risk of development of diseases that threaten the productivity and viability of the birds. The vaccination schedule therefore has to be consequently adapted to the estimated final age of the hens in order to provide them with the best and most prolonged protection. Given this situation, based on the epidemiological environment, the history of the farm and the level of biosecurity, antigen-specific vaccines have to be used in order to provide the birds with the best immunity so that their performance and productivity meet the standards of the genetics companies.

This article reviews the most important points to be borne in mind with regard to vaccination with inactivated antigens, a profitable and effective practice.

2. Priming and Boosting

In order to achieve complete immunity, both cellular and humoral, the administration of 2 to 3 live vaccines is recommended before vaccination with inactivated vaccines. This is known as priming or primary vaccination. This will reinforce cellular immunity and prepare the immunological ground for a better humoral response following the administration of inactivated vaccines. An example of how to measure the development of the protection provided by means of antibody titres is explained in Section 4.3.

3. Manipulations

Doubts have recently been raised as to how many manipulations are necessary for the administration of inactivated vaccines, and certainly there is no specific recommended number. Depending on the history of the destination farm, the epidemiological environment, the type of production and the availability of manpower, the number of manipulations can be greater or fewer, but with priority always being given to the maximum and longest-lasting protection with which we can provide the birds. For example, in countries where the tendency is to vaccinate with live Salmonella Gallinarum vaccine, it is common to reach 5 or 6 manipulations in a rearing batch between live and inactivated vaccines.

The first question that we have to ask is how many manipulations or catches I want or need to do and what is the maximum quantity of inactivated vaccines to be administered on the same day.

This will also be determined by the production system in question, whether it is in cages or in aviaries, as in the latter case there is greater difficulty in handling the birds.

After this, we have to see which diseases we want to vaccinate against, with inactivated vaccines to start the puzzle.

Disease |

Applications |

Yes |

|

1 |

IBV |

1 |

X |

2 |

NDV |

1 |

X |

3 |

EDS |

1 |

X |

4 |

TRT |

1 |

X |

5 |

Pasteurella |

2 |

¿? |

6 |

E. Coli |

2 |

¿? |

7 |

Salmonella |

1-2 |

¿? |

8 |

Coryza |

2 |

¿? |

There is always an initial manipulation when the hen has to be grasped in order to carry out a combined operation involving live vaccines and normally the first inactivated vaccine. This takes place at around 8-9 weeks when an eye drop vaccine is administered (laryngotracheitis), another is given by wing stab (fowl pox and encephalomyelitis) and the opportunity is usually taken to administer the first dose of the inactivated vaccines into the breast. The vaccination schedule can be established on the basis of the manipulations and the vaccines that we want to administer.

It is also recommended that inactivated bacterial vaccines (Avibacterium Paragallinarum, Salmonella, E. coli, Pasteurella M.) are separated into different manipulations, except for vaccines in which the adjuvants allow greater ease of administration, such as aluminium hydroxide, or double oil emulsion (water in oil in water).

Regarding the number of doses for each disease, as mentioned previously, this will depend on different variables. For inactivated vaccines in which there is no live vaccine, as for example for Avibacterium Paragallinarum (coryza), a minimum of 2 applications is recommended in all cases when the threat is medium-low, which can be increased to 3 applications if the threat is considered to be high. The same can be applied to Salmonella, where, depending on the threat and the number of live vaccines that have been administered previously, a second dose of inactivated vaccine will be necessary for layers.

4. Administration

The administration of inactivated vaccines is a very delicate procedure. In order to better understand it, it is a good idea to analyse and verify how they are administered in three different phases (pre-vaccination, vaccination and post-vaccination)

Pre-vaccination

Pay attention to the receipt and dispatch of the vaccines. Global distribution services currently have a cold monitoring system for all orders with the use of thermographs during transport. However, it is always recommended to make sure of this and to verify that the vaccine arrives at the correct storage temperature (2-8ºC) and in optimum condition. When the product has been received, it should be placed in the refrigerator immediately, which should also be kept in good hygienic condition, otherwise the biosecurity of the birds’ vaccine will be put at risk.

Immediately before administration of the product, we must verify that the administration temperature of the inactivated vaccine is within the manufacturer’s specifications, which are normally between 15ºC and 25ºC. This factor can also influence the quality of the administration and of future reactions that can occur if the administration temperature is below 15ºC.

It is also important that the equipment that we use is exclusively for vaccination and that it is clean, calibrated and appropriate.

It is important that the gauge and length of the needle that is used are appropriate. This will depend on whether the administration is intramuscular, into the thigh or subcutaneous, and on the age of the hen. Finally, it should be ensured that the birds are in optimal health, if not it is recommended that vaccination be postponed until the birds recover.

Vaccination

At the time of administration, there is a series of variables that have to be checked and learned by personnel in order to achieve the best possible quality. The condition of the emulsion and the administration temperature, the angle of application, which must be 45º, and administration via the intramuscular route. Often, if the administration speed is too high, we may run the risk of administering the vaccine into the subcutaneous compartment or even causing haematomas and lacerations that can pose a risk to the birds’ development of immunity. It is therefore recommended to palpate the injection site of a few birds that are being vaccinated to check for the presence of the liquid. It is therefore essential to handle the birds gently and not to stress them excessively. The ideal in the injection procedure is for there to be four actions, injection, pressing down, release and removal. Finally, in this section, a change of needle after a maximum of 1,000 birds is considered to be important in order to avoid cross-contamination between birds.

Post-vaccination

There are two forms of post-vaccination analysis, one by means of visual inspection and the other with the use of laboratory analysis.

Visual inspection

This should be carried out between 7 and 10 days after vaccination, with the ideal being an assessment of between 5 and 10 animals per shed.

In the case of inactivated vaccines, whether they are intramuscular or subcutaneous, we have to identify the presence and size of any haematomas and granulomas at the injection site. The best scenario would be for there to be neither, and if there were any, for them to be small.

If, when an inactivated vaccine is administered, a live vaccine such as fowl pox or encephalomyelitis vaccine is also administered into the wing web, if there is a pustule at the injection site this means that it has “taken”.

ELISA monitoring

There are 5 key points to be observed when monitoring the vaccination programme.

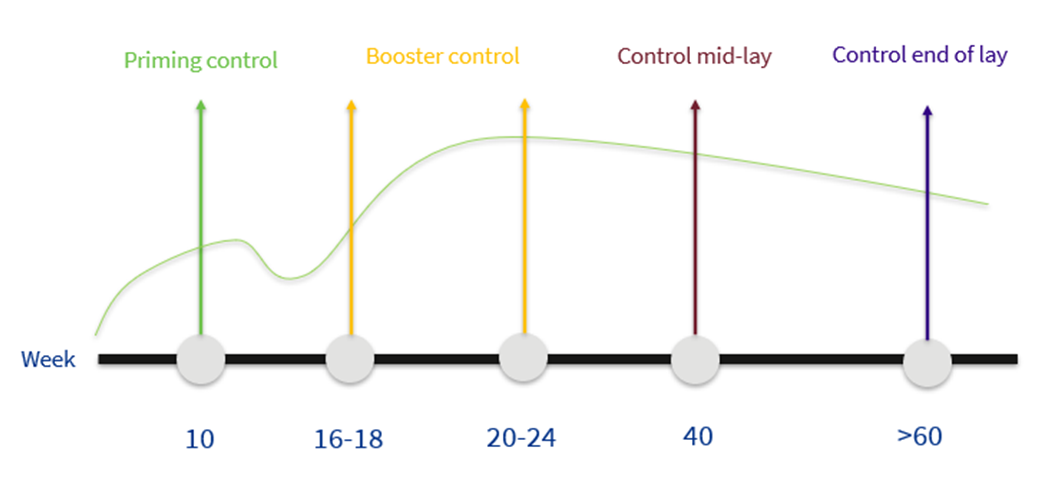

The first point is that the live vaccine schedule should be completed to evaluate how the animals are before vaccination with inactivated vaccines.

Second is the evaluation of the inactivated vaccines which must be carried out first during rearing, just before transfer and subsequently in production just before peak laying to see how the animals are protected before peak production when there is more stress and the threat of disease. It is always interesting at any of these points to look at the EDS titres since, as it is only possible to vaccinate against this disease with an inactivated vaccine, the best parameter to evaluate the application will be the ELISA titre range and especially the coefficient of variation.

Subsequently, it is interesting to monitor again at 40 weeks to evaluate the protective titres once peak laying has passed and to see how well the birds are protected at this time when they still have many weeks of production ahead of them.

Finally, it is convenient to monitor once again at the end of production, from 60 weeks onwards to measure two situations. These birds, which are already of an advanced age, are sentinels of the farm so that measuring the titres at this time will, on the one hand, show us the long-term immunity provided by our vaccination schedule and will also measure whether there is a threat at the end of the cycle.

All this enables us to adjust our schedule over time, which is important as vaccination schedules have to be dynamic based on the different threats that arise.

5. Conclusion

Vaccination forms part of the biosecurity of a farm. The strategy of the vaccination schedule, the administration of the vaccines and the biosecurity measures during its performance (change of needles, use of exclusive equipment, cleaning of utensils…) are all very important.

All of which adds up to the health and welfare of our animals, especially if we also have good biosecurity measures on the farm.

Finally, at HIPRA we consider that the control of administration and monitoring of our vaccines to be key, and therefore, as part of the service that we offer to our customers we include a package of personalised follow-ups to verify that the vaccines are being administered and function correctly.

For more information, please contact our local team in your country.

| References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corella J.; Grillo D.; Blanch, M., | ||||

| (2017) | Comparison of serological results from 3 different vaccination programmes with inactivated vaccine against avian metapneumovirus (aMPV) in Colombia. | WVPA Congress. | ||

| Cristina Gómez Martínez, Francisco Javier Torrubia Díaz, Rüdiger Hauck, Sonia Téllez Peña, Thierry van den Berg., . | ||||

| (2014) | Vaccination in poultry. | Servet. | ||

| Cristina Gómez Martínez, Sonia Téllez Peña., | ||||

| (2016) | Principales retos en avicultura. Vaccinas. tipos, técnicas y protocolos. | Servet. | ||

| Icochea, E.; Condemarin, A.; Losada, J.L.; Apaza, A.P.; Mora, B., | ||||

| (2019) | Comparative protection of different vaccination programmes against Newcastle disease in commercial laying chickens before and after challenge. | WVPAC Congress. | ||

| Ravikumar R, Chan J, Prabakaran M., | ||||

| (2022) | Vaccines against Major Poultry Viral Diseases: Strategies to Improve the Breadth and Protective Efficacy.. Viruses. | 2022 May 31;14(6):1195. | ||

| Sharma JM., | ||||

| (1999) | Introduction to poultry vaccines and immunity.. Adv Vet Med. | 41:481-94. | ||

| Soares L. M.; Fabri F. | ||||

| (2020) | Comparison of fertility after application of two salmonella vaccines containing different types of oil emulsion. | Proceedings of Conference of Research Workers in Animal Disease (CRWAD) | ||