Animal Welfare Audits: What to Expect and How to be Prepared

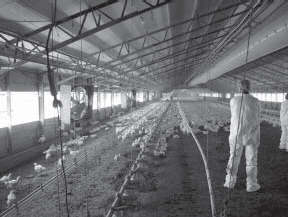

By Susan Watkins, Extension Poultry Specialist at the University of Arkansas's Avian Advice - In recent years customer demand has pressured restaurant chains and retail food stores to assure that the meat, egg and dairy products that they sell are produced in a humane manner. The only practical way these stores and restaurants can provide this assurance is to inspect the production and slaughter facilities of their suppliers such as poultry companies.| More on the Author | |

| Dr. Susan Watkins Extension Poultry Specialist |

|

Introduction

For several poultry operations, animal welfare audits are old news since restaurant chains like McDonalds and

Wendy’s have been requiring supplier audits for several years. However, as more stores and

restaurants feel public pressure to developed supplier animal welfare criteria, poultry companies

that supply meat to several different customers could face a mass of confusing guidelines and audit schedules.

The National Council for Chain Restaurants and the Food Marketing Institute recently addressed the issue of dozens of types of animal welfare audits. Representatives from these trade organizations, representatives of the different meat and dairy industries as well as leading animal welfare experts sat down together to develop one comprehensive audit process. The result was the Animal Welfare Audit Program. Although the audit program is strictly voluntary, it will be difficult for a poultry company to refuse to participate when the request to participate comes from their best customer.

One very good point about the audit is that customers will have the option to decide what level of conformance they are willing to accept. The audit is not a pass or fail program, but rather a process that looks at how well an operation is in conformance with industry derived animal welfare standards.

One major focus of this audit process is an on-farm inspection. For poultry producers, allowing a

perfect stranger to scrutinize their operation and ask specific questions about how they rear their birds can be intimidating. However, by learning the issues that are addressed in an audit, and then preparing well before any audit occurs, a poultry producer can have a positive experience. Such an approach, will allow producers to consider the audit process as an opportunity to view their operation through a fresh and unbiased set of eyes, rather than a necessary evil. In addition, being in conformance with many of the audit questions is actually a reflection of good poultry husbandry techniques. The following paragraphs outline areas of the Animal Welfare Audit Process that will be a part of on farm audits.

Emergency Action Plan

Producers need an emergency action plan that includes contact information for local

emergency services. This list should include not only the fire department and emergency medical services, but also utility company contacts should a power or rural water outage occur. Producers

who use a well as a water source should also include contacts for pump and pressure tank repair on

their emergency contact list. In addition, producers should post a list of poultry company

emergency contacts. Most producers know how to contact their service technicians or feed delivery

personnel, but what if the service person isn’t available, who should then be called?

Producers need an emergency action plan that includes contact information for local

emergency services. This list should include not only the fire department and emergency medical services, but also utility company contacts should a power or rural water outage occur. Producers

who use a well as a water source should also include contacts for pump and pressure tank repair on

their emergency contact list. In addition, producers should post a list of poultry company

emergency contacts. Most producers know how to contact their service technicians or feed delivery

personnel, but what if the service person isn’t available, who should then be called?

Every facility should also prepare a written emergency action plan that addresses what to do

if the facilities are damaged by a storm, or if the ventilation or heating system fails or the feed auger breaks. This plan should include procedures to follow to maintain minimum ventilation and temperature until equipment repairs are completed. After it is written everyone who may potentially be required to follow that plan should become familiar with the plan and how to follow it.

Since most producers have primary responsibility for their operation, they may feel a bit

annoyed by having to prepare a written plan, but remember, it is very difficult to think clearly during an emergency particularly one as devastating as a tornado. A plan and list of contacts that are easily accessible will prevent the confusion often associated with taking action during an emergency situation. There are two additional reasons why a plan can be beneficial. First, if the producer and close family members must unexpectedly have to leave the operation, will the person who must fill in be ready for emergencies? Secondly, putting a plan in writing allows the producer to actually think through the process and identify any weaknesses with the procedure. A well-prepared plan could save thousands of birds in an emergency situation.

A producer will also need to demonstrate that some type of alarm system will function

properly should a power failure occur. Producers need to be prepared to show they can be warned

of an emergency situation no matter where they are or what time of the day it is. An alarm that

consists of a flashing light is helpful for personnel who are in sight of the light and so is inadequate.

Producers need to also be ready to prove that the alarm systems are tested at least monthly and the person responsible for daily bird care must be prepared to show an auditor how the alarm system works.

Adequate Facilities

Producers must provide adequate lighting during the inspection process. Lights too dim to allow the auditor to clearly see the birds’ eyes will not be acceptable. Producers must also be prepared to address the adequacy of feeding and watering systems. There should be a minimum ratio of 1 nipple drinker per 20 birds and one feed pan per 65 birds. If the equipment manufacturer gives different specifications meaning more birds per drinker or feed pan than this, then the producer should be ready to provide this information in writing. Auditors will also check litter quality. The litter should never be over 35 % moisture. This can be measured by pressing a handful together. Upon release the litter should easily crumble apart. If the litter sticks together, then the moisture would be greater than 35%. A rodent control program will also need to be in place. One final point that producers will need to work on with their integrators is monitoring the ammonia level in the bird breathing zone. This must be measured once a week during the last two weeks of grow-out and when measured, should not exceed 25 parts per million.

Flock and Facility Inspection

An additional focus of the audit process is proof that certain tasks are completed. While any

good producer checks his birds at least twice a day, how can an auditor verify this? There should

also be a mechanism in place, which on a daily basis allows producers to confirm that flock health

as well as the feeding, watering and ventilation systems were checked. And if any of the systems

are not working properly, actions taken to return the equipment to normal working order must be

documented. The flock should be checked at least twice a day and signs of abnormal behavior or

illness should be noted. One way to assure a third party that different tasks are completed is to hang a check sheet by the door that a producer or hired hand can initial after morning and evening flock visits.

Although the audit process offers producers some freedom in how to prove they are in

conformance with the daily flock inspections criteria, a daily log or check sheet takes all of the

guesswork out of compliance for both the producer and the auditor. In addition, check sheets may

be just the tool needed to discipline employees into conducting a doing thorough checks each time

since good producers will want to confirm everything is O.K. before they sign off on tasks.

During the audit, a minimum of 100 birds or 25 birds per house, whichever is more, will be

checked for foot pad scores. Birds with any type of burn, ulceration or damage to the pad will

considered to have injured feet. If more than 30% of the birds checked are considered injured, then the facility is out of conformance.

Bird Culling

Birds that are unable to stand or move of their own accord should be removed from the flock on a daily basis and humanely destroyed. Approved methods for culling birds include rapid cervical dislocation (breaking the neck), rapid decapitation (cutting off the head) or asphyxiation using carbon dioxide gas. Under no circumstance will it be acceptable for producers to cull birds by bludgeoning them with a bat or club. Anyone responsible for removing cull birds must show that they have been properly trained in the appropriate culling techniques. Producers must also prove that mortality is removed daily from the production area.

Conclusion

The animal welfare audit program offers a new set of challenges to the production of poultry.

Unfortunately, this challenge will not go away as long as less than 2% of the population is producing food and the other 98% of the population expects some type of assurance that the animal products they consume were humanly produced. Because of the broad scope of the National Council of

Chain Restaurants and the Food Marketing Institute, most poultry companies will probably be

required to address these standards through on-farm audits. Therefore contract producers that

expect to remain economically viable must be ready to make the transition to animal welfare

auditing. By developing an animal care program that is consistent yet easy for a third person

unfamiliar with the day-to-day operations of their specific farm to understand, producers will be

well on their way to proving their operation is in conformance with the animal welfare standards.

Source: Avian Advice - Winter 2003 - Volume 5, Number 4