Effective Biosecurity: The Case for Compliance and Regional Perspective

Effective Biosecurity: The Case for Compliance and Regional Perspective - By W.E. Morgan Morrow, North Carolina State University - This year at the annual meeting of the American Association of Swine Veterinarians in Toronto, Canada, Dr. Jena-Pierre Vaillancourt of the Poultry Health Management Team, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Montreal, Saint-Hyacinthe, Quebec gave an invited lecture: Effective biosecurity: The case for compliance and regional perspective.

Dr Morgan Morrow Swine Veterinary Specialist |

Introduction

“Nation will rise against nation and kingdom against kingdom, and there will be great earthquakes, famines, and plagues in various places. There will be terrors and great signs from heaven."

This is how Luke describes the end of the world in the year 70. At the time, some people of Thessalonia elected to stop what they were doing. After all, the end was near. Of course, the concept of time can be quite relative. Again, we are living in a time of wars and natural disasters that seem to be increasing in incidence. The same can be said about epidemics in animals and humans. In fact, we are told to prepare for the next Influenza pandemic. Pessimists believe that worldwide human fatalities could reach numbers similar to the US population! Veterinarians can already share impressive numbers.

Millions of birds destroyed in Italy (1999-2001), Mexico (2000), Virginia (2002), California (2002-2003), British-Columbia (2004), Asia (2003-present), etc. In pigs, Foot-and-Mouth disease epidemics have severely affected regions of Europe and Asia over the past few years. But parallel to these well-known infectious diseases, swine veterinarians have had to face relatively new challenges, such as the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. The same can be said of poultry veterinarians who have observed the emergence or re-emergence of 26 new diseases (or new variants of known diseases) since 1978. An average of one a year. This description of recent events may resemble that of Luke’s almost 2000 years ago; but we know that doing nothing is not an option.

Current infectious disease events are occurring at a time when more restrictions are placed on veterinary drugs and when there is a growing concern by the public over the safety of the food supply. Right or wrong, the conjuncture is negative. To face this situation, the emphasis has turned towards enhanced biosecurity. In fact, if you are reading this paper, it is because you already know about the importance of biosecurity and you have already heard a few talks about it. So, what’s new? Not much in terms of farm biosecurity measures. We have known for years how to biosecure such premises. Every swine company has a biosecurity plan on file. But the implementation is just not done consistently. People do not comply.

This is true at different levels in the production system. First, the growers. They are key to the disease control effort. Dr. Charles Beard from the US Poultry and Egg Association put it clearly: “If the growers are not brought into the effort to upgrade the biosecurity situation in the U.S. poultry industry, very little will be accomplished. The grower level is where the biosecurity effort needs to be concentrated because that is where the birds are.” The same goes for swine producers. However, in today’s animal production, it is no longer possible to biosecure an industry one farm at a time. In other words, for a given region, poultry and swine veterinarians also need to develop a regional perspective to biosecurity. Hence, this paper will focus on compliance issues, and on the regional approach to biosecurity for disease prevention and containment.

Compliance

In the medical field, compliance is defined as “the extent to which a person’s behavior coincides with medical or health advice” (Haynes et al, 1979). In the medical profession, compliance has been studied for several decades because non-compliance is often associated with treatment or disease prevention failures. We face the same challenges as veterinarians, even more so when it comes to the implementation of biosecurity plans.

In medicine, there is a discrepancy between doctors’ perception of compliance and reality. In 1984, Nagy reported that 75% of outpatients self-reported taking medication as prescribed all the time or usually, while doctors estimated 95% . Gilbert (1980) showed that the ability of family doctors to predict the compliance of patients was no better than chance, even for patients they had known for years! Similar observations apply to veterinarians and food animal industry leaders.

In early 2000, a census of all employees working on turkey breeder farms for an integrated company was conducted. These farms were all shower-in shower-out. The assumption was that all employees and visitors were complying with tough biosecurity rules. Employees were surveyed individually and in their native tongue (Spanish or English). Confidentiality of individual responses was clearly explained. The results highlighted the inconsistency between management and employees.

The important message here is that what company management perceives as happening on farms and what actually happens on a daily basis can be two different things. This can be very significant when it comes to biosecurity.

In an earlier investigation, all people working on or visiting farms under contract with a North Carolina turkey company were asked to sign in for each visit. This included the grower and family members, farm personnel, service people working for the integrated company, veterinarians, feed truck drivers, utilities company people, etc. A mailbox was installed on each farm. Log-in cards requesting key information were made available. These farms were located in an area where poult enteritis mortality syndrome, a severe enteric disease of turkeys, was highly prevalent. The company instituted the log-in system as part of a series of measures designed to reinforce the existing biosecurity program. In order to determine the degree of compliance for this new recording system, a hidden camera was installed on three farms to monitor their entrance 24 hours a day for 7 consecutive days. Based on this surveillance, it was clear that many people did not comply, with a compliance level ranging from 7 to 49%. Non-compliance was not limited to visitors who were not working for the poultry company or the farm. For example, feed trucks were observed driving on the farm without logging in late at night, even after drivers, who are working for the integrated company, were instructed to do so.

Economic models developed to assess the value of biosecurity systems suggest that prevention of disease in the end is always less expensive than treatment (Morris, 1995). Gifford et al (1987), working on a model for broiler breeders, confirmed “that expenditure on protective measures can be justified by both the risk of introducing a disease and the magnitude of losses that may occur following infection”. On a broiler breeder farm, the benefit-cost ratio of biosecurity is at least 3 for a farm considered at a 30% risk of being infected by an agent causing a severe disease. In the case of the most pathogenic conditions, they found that investment in biosecurity was justified even with a 0.01 probability of outbreak. Estimating the risk of disease is partly a subjective exercise. However, substantial evidence has been reported regarding major risks such as:

Poor farm location: farm located in high density region (other farms within 2 km of premises)

Introduction of animals of unknown origin

Introduction of contaminated material or infected animals

Presence of an infectious disease of interest in a region

Presence of this disease in neighboring farms

Pest infestation (rodents and/or insects)

Poor sanitation

No restrictions or requirements for visitors (i.e., high on-farm traffic, including hired help going from farm to farm)

These are common sense hazards that must be considered when estimating the risk of disease transmission. Although self evident, these risks are often ignored in practice. A similar situation exists in human medicine where significant health risk and protective factors are often neglected by patients. In the 1950's, the United State Public Health Service developed the Healthy Believe Model to explain such behavior (Rosenstock, 1974). This model proposes that health risk assessment is determined by the individual’s perception of:

His level of personal susceptibility to the particular disease;

The degree of disability that might result from contracting this condition;

The health action’s potential efficacy in preventing or reducing susceptibility or severity;

Physical, psychological, financial barriers or costs related to compliance;

This model may very well apply to a grower’s perception of risk for his flock or herd. One can also assume that this belief model pertains to the decision-making process of managers of integrated companies, shaping their appreciation of risks and of biosecurity measures. One supportive evidence is the fact that a similar proportion of poultry people comply with biosecurity measures as the general population does for disease prevention strategies designed to help them.

Assessing risks is assessing reality. Recent events in many regions of the world are forcing this on us. But what is the knowledge or sensitivity of all industry people (and of those working for satellite organizations) relative to such current events? How many are truly aware of the most significant risks? Execution of a biosecurity plan (i.e., compliance) very much depends on how educated these people are on contagious disease issues. Too often, this is where the system fails. Employees are told what to do, but without a good understanding of the “why,” it is not possible to reach the compliance level required to make a biosecurity program work. One could go one step further and state that, to achieve long-term benefits, we need more than just education. We need a paradigm shift.

Need for a Paradigm Shift

A paradigm is “a shared set of beliefs or assumptions that defines the ways in which we think and act.” It establishes or defines boundaries and it tells you how to behave to be functional within them. That is how societies work…and clash. Indeed, any information which does not fit the paradigm is usually, at best, ignored. At worst, it triggers a very negative reaction. California experienced this when people with backyard flocks and live-bird markets started moving birds around, i.e., increasing animal traffic, during the effort to quarantine and reduce traffic to contain the Newcastle epidemic of 2002-2003.

For these people, the risk and impact of loosing their birds and/or business was considered much greater than the risk and impact of spreading a very virulent virus throughout the community. In a recent stimulation of an avian influenza outbreak in Ontario, Canada, this behavior was a consideration in delaying regional traffic control. The concern was that any initial effort by the poultry industry to control traffic (other than to restrict the movement of industry vehicles) could spark a flurry of activities by non-commercial growers (and even some commercial growers; since this industry is not fully integrated in this region, growers own their birds and could elect to send birds to slaughter sooner to avoid an upcoming federal quarantine).

Therefore, our long-term objective should be to shift from the old paradigm (animal production seen as a mechanical process largely dictated by accountants; animal ownership and trading seen as an individual right independent of environmental and disease conditions) to one where health risks are factored in by all participants. This will likely be a long process.

“Scientific progress occurs, not by slow incremental accumulation alone, but also by occasional “revolutions,” in which “an older paradigm is replaced in whole or in part by an incompatible new one” (Kuhn, 1962).

We may be in need of a “revolution”, but we must also be realists. Nonetheless, we have enough evidence, i.e., epidemics, in the world right now to be in no position to plead ignorance if the next outbreak affects our own region.

The New Paradigm: The Case for Regional Biosecurity

All animal activities comprise disease transmission risks and these risks augment in significance as the regional density of such activities increases. Therefore, the management of infectious disease risks must include a regional approach in terms of disease prevention as well as disease containment.

Improvement in biosecurity compliance at the regional level parallel improvements in communication within and between companies. The stigma attached to having an infectious disease is real and often leads people to keep this information from others. Just being suspected of having a diseased flock or herd may be enough to stop exports or affect business agreements. But silence has been shown to be even more costly. Although liability will always be a concern, pointing fingers has never been an effective disease control strategy and companies sharing a region must also share the necessary information needed to contain contagious diseases.

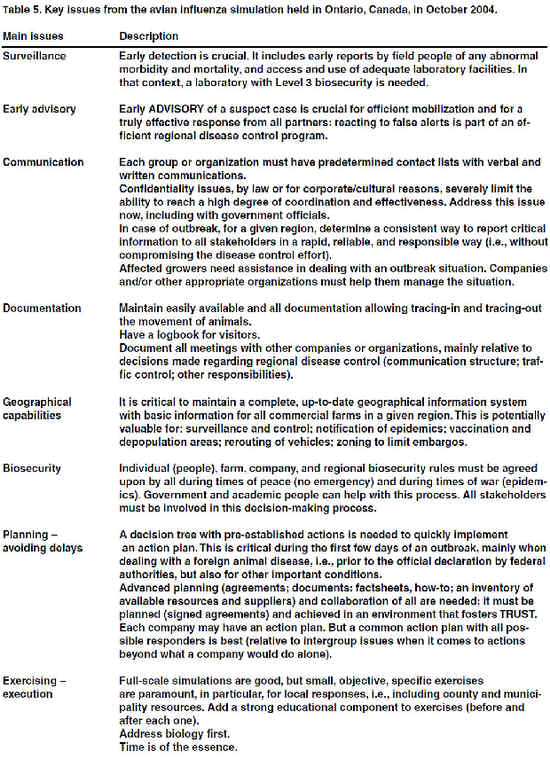

A full scale simulation of an avian influenza outbreak was held in late October 2004 in Ontario, Canada. The simulation focused on what they called the ”grey zone”. This is the period between the observation that a severe contagious disease may be in a region and when clinical and/or laboratory evidence would allow the federal government to declare that a foreign animal disease is present. An audit of this simulation revealed that key issues centered around the ability to detect rapidly an initial case and to communicate effectively within an between companies and organizations to implement all necessary measures to control the problem (Table 5).

Key industry leaders and decision-makers from local governments must receive the epidemiological information needed to act quickly if an epidemic emerges. Geographical information systems (GIS) are fast becoming routine tools out of the necessity to quickly determine the location of infected or diseased flocks/herds. This technology serves several purposes:

It is used primarily by industry to determine at-risk areas and to establish the best routes to avoid infected flocks or to avoid at-risk farms with contaminated material or infected animals

It is also useful to assess the geographical distribution of epidemics

It identifies clustering and permits the statistical evaluation of flock/herd health status associated with proximity to specific sties

It is a powerful investigative tool when coupled with molecular techniques providing critical information on spread of disease agents.

This is not new technology, but its acceptance and use will hopefully grow over time. It requires accurate, up-to-date data to be of value. Each company or organization in a region must comply. The best way to achieve this is to have an individual within each company responsible for the implementation of biosecurity measures and for regional issues. Whoever is charged with maintaining the GIS in a specific region (e.g., a state) must also communicate effectively with all participants to preserve the integrity of the system.

Confidentiality is important. But when it prevents the timely flow of information to people who could act on it to prevent disease spread, it becomes the microbe’s best friend. Doable confidentiality agreements must be reached for routine and for emergency activities if we are to establish proper regional biosecurity and disease control plans.

If we have learned anything from disasters such as the Foot-and-Mouth epidemic in the UK or the Avian Influenza outbreaks in Italy is that time is of the essence. The successes of the modern poultry and swine industries have also created an environement very favorable to highly contagious agents. In this environment, the window of opportunity to contain an epidemic is very narrow.

Local governmental institutions, including universities, must play a greater role because they offer a relatively stable environment for a specialized work force very much needed by industry for disease surveillance and control. Although technological advancements will certainly mark the next 10 years, it is people related issues that will have the most significant impact on our ability to biosecure the poultry and swine industries.

Given the large size of farms and the high regional density in many swine and poultry production areas, any serious contagious disease situation can potentially turn a peaceful rural community into a war zone. Getting ready for it makes sense. It requires planning, practice, and above all, the right attitude. One that is visionary and resolute.

Sir Winston Churchill said it best: “War is a game that is played with a smile. If you can’t smile, grin. If you can’t grin, keep out of the way till you can.”

References

1. Bossidy L. and Charan R. 2002. Execution. The discipline of getting things done. Crown Business, New York, New York. 278 pages.

2. Haymes, R.B., Taylor, D.W., Sackett, D.L. 1979. Compliance in health care. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore; 516 pages.

3. Gifford, D.H., S.M. Shane, M. Hugh-Jones, and B.J. Weigler, 1987. Evaluation of biosecurity in broiler breeders. Avian Dis. 31:339-344.

4. Gilbert. Predicting compliance with a regimen of digoxin therapy in family practice. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1980 Jul 19; 123(2):199-22.

5. Kuhn, 1962. www.psychadvantage.com/glossary.html.

6. Morris, M.P., 1995. Economic considerations in prevention and control of poultry disease. Pages 4-16 in : Biosecurity in the poultry industry. S.M. Shane, D. Halvorson, D. Hill, P. Villegas, and D. Wages, ed. Am. Assoc. Avian Path.

7. Nagy, VT, Wolfe GR. 1984. Cognitive predictors of compliance in chronic disease patients. Med Care. Oct; 22(10):912-21.

8. Rosenstock, I.M., 1974. Historical origins of the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Monogr. 2:328-335.

9. Sackett, D.L. and J.C. Snow (1979). The magnitude of compliance and noncompliance. Compliance in Health Care. R.B. Haynes, D.W. Taylor and D.L. Sackett. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press: 11-22.

Source: North Carolina State University Swine Extension - May 2005