Fighting Newcastle and Other Poultry Diseases

Researchers with the USDA Agricultural Research Service in Athens, Georgia, have reported progress in their work to prevent outbreaks of Newcastle disease and other diseases that pose a risk to poultry producers across the world.Newcastle disease (ND) is one of the most prevalent viral diseases of poultry in the world with at least 68 countries reporting outbreaks in domestic poultry from 2013 to 2014. Virulent strains of Newcastle disease virus, which cause the disease when they infect birds, are not found in domestic or commercial poultry in the United States, but are endemic in many countries of Asia, Africa and The Americas.

The disease is highly contagious and is so deadly that up to 90 per cent of non-vaccinated birds may die, and some without showing any signs of disease.

At the Agricultural Research Service's Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory (SEPRL) in Athens, Georgia, scientists use different methods to help prevent outbreaks of ND and other poultry diseases that pose a risk to US poultry producers. These include creating vaccines that induce more effective immune responses with fewer side effects and developing more stringent methods to evaluate ND vaccines.

Vaccines that Target Two Viruses

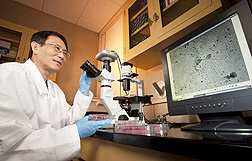

(Image: USDA)

SEPRL microbiologist Qingzhong Yu and his colleagues recently created a new vaccine that protects chickens against infectious laryngotracheitis virus (ILTV) and virulent Newcastle disease virus.

Like ND, infectious laryngotracheitis (ILT) is one of the most economically important infectious diseases of poultry-causing sickness and death in domestic and commercial poultry and wild birds.

The new vaccine helps reduce virulent virus shed – excretion of virus by the host – and the transmission of disease from infected birds to healthy ones, said Dr Yu, who works in SEPRL's Endemic Poultry and Viral Diseases Research Unit.

He said: "Although the ILTV live-attenuated vaccines used today are effective, some of the viruses used to make them can regain virulence – causing the side effect of the chickens becoming chronically ill.

"Other vaccines can protect birds from clinical signs, but do not reduce the virus shedding very well." Because they do not reduce the risk of virulent ILTV transmission to uninfected birds, these other vaccines are not very effective, he adds.

In his study, Dr Yu generated new vaccines by inserting a gene from the ILTV into the Newcastle disease virus (NDV) vaccine strain LaSota, which has been used for more than 50 years worldwide as a vaccine to prevent poultry from getting Newcastle disease. The new vaccine was tested in more than 200 chicks. All vaccinated birds were protected against both ILTV and virulent strains of NDV.

Dr Yu said: "These vaccines were shown to be stable, safe and effective. The birds, which were vaccinated at ages one and three days and challenged with virulent ILTV at the age of 21 days, showed no clinical disease signs and no decrease in bodyweight gains."

ARS has filed for a patent on the vaccine invention, which can be administered by aerosol or drinking water to large populations of chickens at a low cost, according to Dr Yu.

Improving Vaccine Evaluation Protocol

(Image: USDA)

The survival rate for healthy chickens vaccinated with available commercial Newcastle disease (ND) vaccines is 90 to 100 per cent.

Current vaccines also perform well under field conditions in countries where virulent strains of NDV are not endemic. However, these same vaccines frequently fail to protect birds in countries with highly virulent viruses.

"This discrepancy is a contentious topic for those interested in Newcastle disease," said microbiologist Claudio Afonso at the Agricultural Research Service's Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory (SEPRL) in Athens, Georgia. "Some veterinarians are requesting genotype-matched vaccines, while others believe the application of the vaccines is faulty."

A new improved NDV vaccine evaluation procedure, developed by Afonso and veterinary medical officer Patti Miller in SEPRL's Exotic and Emerging Avian Viral Diseases Research Unit, could help settle the inconsistency of vaccine performance.

Dr Miller said: "Antibodies produced after a bird is vaccinated with any strain of NDV should be able to protect against virulent virus challenges, because all NDV strains are closely related.

"This is true when conditions are optimal, meaning vaccinated birds are healthy, they receive the correct viable vaccine dose, and they have two to three weeks to develop an immune response before being exposed to virulent strains of Newcastle disease virus.

"Under perfect conditions, many vaccines do work, but conditions are not always perfect in the field,. Chickens should get a certain vaccine dose but sometimes get less. Sometimes they don't have three weeks to develop an immune response before being exposed to the virus. When we make conditions less than perfect in our experiments, we can actually pick a better vaccine virus for a particular virus challenge."

The traditional evaluation procedure is not designed to compare vaccines and only measures survival rates under optimal conditions, she added.

Dr Afonso explained: "We improved the testing procedure by comparing a vaccine made with the same virus strain-genotype used in the experimental challenge to a vaccine made with a different genotype.

"The new procedure involves using multiple vaccine doses and an early challenge with a highly virulent virus dose. It also allows us to see differences in clinical disease and in survival after virus challenge."

In the study, scientists mimicked conditions that sometimes occur when birds are vaccinated in the field. Using the improved procedure, chickens were inoculated with different vaccines and then challenged with a high dose of virulent NDV one or two weeks later. Chickens that received the genotyped-matched vaccine had superior immunity responses, reduced clinical signs, and increased survival compared to birds vaccinated with a different-genotype vaccine.

Under the traditional procedure, no significant differences in survival rates were found between the vaccines.

Dr Afonso said: "With this rigorous comparison, which provides a thorough evaluation, we showed for the first time that a significant reduction in death can be detected with genotype-matched vaccines."

The upgraded procedure is not being suggested for vaccine approval, Dr Miller explained. However, it could be used by scientists to develop an improved vaccine and help veterinarians choose a more appropriate vaccine to treat birds for NDV in countries where virulent viruses are endemic.

April 2015