GB Emerging Threats Report – Avian Diseases – January to March 2011

Among the highlights of this report – previously known as the Quarterly Surveillance Report from VLA – are a new condition affecting eggshell quality, the finding of a new pathogen associated with infectious coryza and fowl cholera was diagnosed in a free-range layer flock.Highlights

- Submission trends: Stable numbers of avian diagnostic submissions received by the VLA and SAC compared with Q1-2010 with an increase of 13 per cent from Q4-2010. Increase of one-third recorded for the total number of non-carcass avian submissions to VLA and SAC in Q1-2011 compared with Q1-2010. Since 2007 some 90 per cent of Q1 avian diagnostic submissions from chicken flocks.

- New & Emerging diseases: Investigation of a case of suspected Eggshell Apex Abnormalities (EAA) in a free-range layer flock, putatively associated with M. synoviae and IBV. Different Avibacterium paragallinarum serovars identified from chicken flocks with infectious coryza.

- Unusual diagnoses: Fowl cholera diagnosed in free-range layers and local populations of greylag geese and other wild birds.

- Changes in disease patterns & industry: Newcastle disease outbreaks due to PPMV-1 in northern Europe. Health issues following the severe winter conditions. Pressurised margins and difficult operating conditions due to high production costs, including feed and gas prices, variable chick quality and low wholesale and retail prices.

New and Emerging Diseases

During Q1-2011 no new and emerging diseases were identified from analysis of available avian scanning surveillance data and information for broilers, broiler breeders, layer breeders, turkeys, ducks and geese, game birds and backyard flocks. However, one new and emerging disease investigation was undertaken in commercial layer chickens.

Suspected Eggshell Apex Abnormalities in a free-range layer flock

A case of suspected Eggshell Apex Abnormalities (EAA) in a flock of 14,000 free-range layer chickens was investigated. EAA was first identified in European layer flocks approximately 10 years ago, and is associated with infection of the oviduct by certain strains of Mycoplasma synoviae (Ms; Feberwee and others, 2009; Catania and others, 2010). In chickens, other endemic conditions caused by Ms (joint disease and/or subclinical respiratory tract infections) are well described. Ms may be treated with antibiotics but responses can be variable. Ms vaccines do exist but none is currently licensed in the UK. EAA is of no known or recognised public health significance.

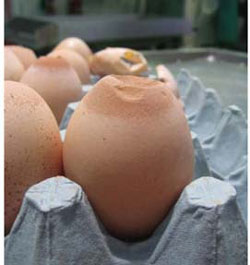

EAA results in the production of abnormal eggs with characteristic shell defects where one end of the eggshell (the sharp end, or ‘apex’) is thin and roughened or virtually shell-less. Characteristically affected eggs are described as having a ‘glass top’, with a sharp zone of demarcation from the rest of the shell (Figures 3-5). Affected eggs are very prone to breakage. The range of abnormal egg production can vary from one to two per cent up to 25 per cent in an affected flock, and typically continues for the remainder of the laying period following onset (Feberwee and others, 2009). Therefore, there may be considerable financial losses in affected flocks, in proportion to the scale of abnormal egg production. Additional labour costs may be incurred due to sorting abnormal eggs and cleaning breakages that cause contamination of unaffected eggs. Affected flocks may be depleted early if they become financially unviable.

Preliminary results from the current flock investigation in GB include detection of Mycoplasma synoviae (Ms) from the respiratory tracts of birds producing eggs with EAA and unaffected hens. Testing of the oviducts of affected and unaffected birds continues, but has not yielded Ms to date. However, the flock seroconverted to Ms around 45 weeks and the EAA eggs also started to be seen at this time. Furthermore, immunoblot serology has shown Ms (and M. gallisepticum) antibodies in egg yolk and serum of birds sampled at 67 weeks. Various treatments with antibiotics with anti-mycoplasmal activity and supplemental vitamin D were administered, with little effect either on egg production or the occurrence of EAA. It is also reported that the severity of EAA episodes may be exacerbated by concurrent infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) infection. There was evidence of exposure to IBV in the affected flock. However, the flock was subject to a routine of regular live IBV vaccinations in-lay. A drop in egg production was seen after each of these IBV vaccinations, and it is possible that they may have exacerbated clinical manifestations of EAA.

This episode appears consistent with descriptions of EAA reported elsewhere and investigations continue. Veterinarians should therefore consider EAA as a differential diagnosis of eggshell quality problems in layer flocks in GB, particularly if eggs with the characteristic ‘glass top’ appearance are described. Following completion of the ongoing investigations into this case, further information will be provided. AHVLA would also be interested to hear of any other suspected EAA cases.

Ongoing New and Emerging Disease Investigations

Infectious coryza in chickens

The detection and confirmation of infectious coryza (fowl coryza) in hobby chicken flocks in England were reported in 2010 (Welchman and others, 2010). The disease is caused by Avibacterium paragallinarum and different strains (serovars) of the organism are recognised. Serotyping of A. paragallinarum (Apg) isolates from the flocks in southern England affected during 2010 was carried out, courtesy of an Australian laboratory. These were identified as being Apg serovar A strains. An isolate originating from northern England in 2008, which was not confirmed as being Apg until 2010, was identified as serovar C. This indicates that both of these serovars have been present in GB, and that the cases in 2008 and 2010 were of different origin.

Further information relating to the epidemiology and control of infectious coryza is available online from AHVLA (click here) and details of the cases detected in England during 2010 have been described more fully (Anon, 2010; Welchman and others, 2010). Neither of the Apg serovar A or C strains are of public health significance. The clinical presentation of disease in chickens is likely to be similar. There is the potential for onward transmission of infection to commercial flocks, particularly if good standards of biosecurity are not practised. There also remains a risk of introduction of the disease via commercial movements from outside of GB.

Veterinarians should consider infectious coryza as a differential diagnosis of upper respiratory tract disease, especially in chickens. The situation will continue to be monitored.

There were no other ongoing new and emerging disease investigations during the quarter.

Previous new and emerging disease investigations (including infectious coryza) are described in previous quarterly VLA avian disease surveillance reports. These reports and other advisory material for vets and poultry producers are available on the VLA web site click here. Surveillance activities continue to monitor for the presence of any potential new and emerging or reemergent disease threats in the GB poultry population.

Unusual Diagnoses

Fowl cholera in free-range layers

Sudden deaths were reported in a flock of free-range layers over several days with loss of approximately 25 birds from the group of 150. Fowl cholera was diagnosed with isolation of Pasteurella multocida in septicaemic distribution. Fowl cholera was also diagnosed in December 2010 in Greylag geese (Anser anser) found dead approximately 8km from the poultry site. Further deaths in wild waterfowl and seabirds occurred in January 2011 at a location approximately 40km from the initial site and fowl cholera was also diagnosed. Spread from wild birds to the poultry flock was suspected as the origin of infection. Outdoor poultry husbandry systems carry the inherent hazard of wild bird contact. Steps to minimise contact are recommended as part of flock biosecurity and management practices. No wider threats were recognised and no specific actions required other than for producers and veterinarians to maintain vigilance for disease problems and investigate as appropriate.

Changes in Disease Patterns, Industry and Risk Factors

Disease Patterns

Health and disease problems following the severe winter conditions

Disease problems were identified as anticipated following the severe winter weather conditions during December 2010 and January 2011 (click here). In particular, stunting, unevenness and poor litter quality were seen in broiler flocks, together with reports from PVS and poultry company vets of ‘dysbacteriosis’ and wet litter. Investigations of some poor performing flocks revealed no consistent findings in stunted birds compared with birds that were doing well, and no likely cause of the problem was identified. Many of these cases were attributed to the shortened turnaround times and poorer cleanouts between successive broiler crops related to the extreme winter weather. Previous experience within affected companies indicates that once issues such as this are resolved and cleanouts and ‘downtime’, i.e. the time when the farm is completely empty of birds, are back to normal, such broiler health problems usually diminish markedly.

Discussion with PVSs also indicated that the incidence of broiler ascites syndrome had increased during the prolonged cold spell. Gas price increases and problems with gas deliveries during the severe weather meant, in many cases that house ventilation was reduced in an attempt to reduce fuel consumption. Such situations will frequently result in greater numbers of fast growing broilers developing pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure with ascites. Increased diagnoses of the condition were not recorded in diagnostic post-mortem submissions to AHVLA or SAC. This is because broiler ascites is readily recognised by experienced managers, or is detected when birds are caught up at depletion.

In addition, there are ongoing shortages of hatching eggs and broiler chicks in the UK. This can sometimes lead to variable chick quality at placement and higher than usual first week mortality rates. Poor starts in broiler crops can also lead to unevenness of the birds, which may, in some circumstances, threaten the profitability of a flock.

The situation will continue to be monitored through routine scanning surveillance activities and PVS contact.

Newcastle disease in Europe

Newcastle disease (ND) outbreaks in unvaccinated poultry were officially reported by two northern European countries during Q1-2011, associated with pigeon paramyxovirus type 1 (PPMV-1) infection (OIE, 2011). Wild birds were suspected to be the source of infection, gaining access to poultry houses during the severe winter conditions. PPMV-1 is a virulent ‘pigeon variant’ ND virus. When PPMV-1 is found in any poultry species the infection must be regarded as ND under EU legislation, with resultant sanitary and other disease control measures. The two most recent ND outbreaks in the UK (in 2005 and 2006) occurred in game bird flocks, initially detected by VLA-RL scanning surveillance activities. The origin of the ND outbreak affecting pheasants during 2005 was traced to the movement of poults from France. In 2006, PPMV-1 infection was detected in grey partridges (Perdix perdix) in Scotland (Aldous and others, 2007; Irvine and others, 2009).

These ND outbreaks serve as a reminder of a number of existing threats to UK poultry, specifically:

- Virulent ND viruses, including PPMV-1, pose a continuing risk of avian notifable disease incursion to poultry populations.

- PPMV-1 is frequently isolated from pigeon lofts and is endemic in feral columbiformes. These populations represent sizeable reservoirs with potential for spill over to domestic poultry.

- The clinical signs of ND in game birds in the UK were different from the classical presentation of an acute, severe disease typically seen in chickens. Therefore, early detection based on observation of clinical signs through passive surveillance may be impaired.

- An estimated 25 million game bird poults are released during the game bird season in the UK, 80 per cent of them pheasants. This includes the movement of approximately 10 million pheasants from France (Canning, 2005).

Some of the risk pathways may be mitigated by ensuring good biosecurity, in common with preventative measures for other avian notifiable and infectious diseases. Following consultation with the VLA, the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust were taking forward messages regarding disease awareness with game sector groups. It is also suggested that any clinical presentation in game birds that includes progressive central nervous system signs coupled with unexplained rising mortality and/or production problems should prompt consideration of avian notifiable disease as a differential diagnosis. Therefore, vigilance for disease problems is advised with prompt investigation and reporting to the veterinary authorities as appropriate.

H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI)

VLA, in collaboration with Defra monitors the international situation and distribution of avian notifiable disease outbreaks. Q1-2011 has seen an increase in the number of officially reported outbreaks of H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Notifiable Avian Influenza (HPNAI) across East Asia. This includes widespread outbreaks in domestic poultry and wild birds in South Korea and Japan. In addition, there have been reported outbreaks in domestic poultry in Hong Kong, Cambodia, Myanmar, Viet Nam, Bangladesh and India since the start of 2011 (OIE, 2011). This includes the detection of viruses of the recently emerged H5N1 HPNAI clade 2.3.2. from both poultry and wild birds. Previously, only H5N1 HPNAI clade 2.2 strains have been identified in both of these bird populations.

In Europe, the first reported detections of H5N1 HPNAI clade 2.3.2 viruses occurred in March/April 2010 affecting backyard poultry in Romania and a wild Common buzzard (Buteo buteo) found dead in Bulgaria (Anon, 2010a; Reid and others, 2011). No further outbreaks in Europe have been reported to date despite continued surveillance. In the UK and the EU, a continual low risk of incursion of avian notifiable disease into poultry populations exists. Prevention is assisted by good biosecurity on poultry premises, including limiting contact with wild birds (Defra, 2011). Over the period 2005-2008, seven avian notifiable disease outbreaks occurred in poultry in GB. Four of these were initially detected through avian disease scanning surveillance activities at VLA-RLs. Therefore, vigilance through existing scanning surveillance activities, with prompt reporting of suspected avian notifiable disease to the veterinary authorities remains essential.

Further Reading

| - | You can view the full report by clicking here. |

| |

- | Find out more information on the diseases mentioned by clicking here. |

June 2011