Modern Birds Have Expensive Tastes

While great strides have been made in improving commercial traits of layers and broilers, the difference between the cost of production and the returns realised still governs whether these traits are worth realising to the full. Prof Rob Gous, Emeritus Professor at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, talked to Glenneis Kriel about this issue.Genetic improvement has resulted in “new era birds” that will outperform their counterparts of a couple of decades ago in virtually all commercial traits when subjected to similar production environments.

Whether these birds will reach their full production potential, however, still depends on external factors, such as diet, climatic conditions and lighting, with costs being the main consideration when it comes to the manipulation of these factors.

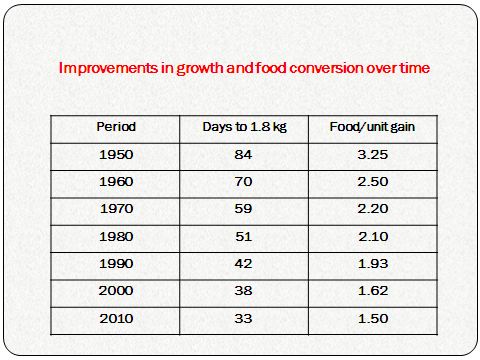

Prof Rob Gous, Emeritus Professor at the University of the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa pointed out that broilers have improved to such an extent that it now takes about 30 days to produce a 1.8 kg bird with only 1.5 kg of feed, in comparison with 84 days and with 3.25 kg of feed back in the 1950s. The expectation is that birds will reach 1.8 kg in only 28 days with 1.4 kg of feed by 2020, with some broilers already achieving this goal.

Progress, according to Prof Gous, is due to geneticists selecting for faster growth, but at the same time for stronger bones, less body lipid, greater resistance to environmental stresses and diseases and other traits. The result is that these birds are highly efficient, but require better nutritional and environmental conditions than in the past to achieve their full genetic potential.

Prof Gous said that the same applies to layers. To realise their genetic potential, laying hens have to be fed correctly, subjected to a lighting programme that ensure they reach sexual maturity at the right time in terms of somatic maturity and vaccinated to ensure immunity to the diseases prevalent in the area where they spend their adult life.

High temperature

Prof Gous identified high temperature as the greatest obstacle preventing broilers from realising their genetic potential in countries like South Africa: “To grow at their potential, broilers generate a great deal of heat in maintaining themselves, in walking about and feeding, in digesting food and in the process of depositing protein and lipid in the body. This heat has to be lost to the environment if the bird is to keep its body temperature constant.

“As environmental temperatures increase, the ability of broilers to lose sufficient heat to the environment to enable them to grow at their potential is becoming more and more difficult, and will soon become impossible as the rate of potential growth increases,” Prof Gous said.

A possible solution would be to select birds with a lesser feather cover that would enable them to release more heat from the body. Prof Gous pointed out that this would however result in other challenges, such as damage to the skin.

The only solution, according to him, is to keep the broilers in houses where the temperatures could be reduced to lower levels than was presently the case. This would, however, render buildings even more expensive, and it might not be worth striving to achieve potential growth because of this extra cost.

Balanced diet

Poor diet and nutrient deficiency has always been associated with poor feed efficiency and weight gain in broilers and reduced egg production, low egg weights and poor egg shell quality in layers. These can also lead to metabolic disorders in broilers and layers.

A lot of research has been done to fine-tune nutrition according to the requirements of these modern birds and there has over time been a shift in the way diets are being formulated: energy units have changed from productive energy to metabolisable energy and some nutritionists today use a net energy system.

Similarly, crude protein was the unit used to ensure an adequate supply of protein in the long-distant past, until amino acids were recognised and minimum levels were set. Nowadays the total amino acid levels have been replaced with digestible amino acid levels, which is a more accurate means of determining the amino acid content available to poultry in each of the ingredients used.

Prof Gous said that chickens will always attempt to grow or reproduce at their potential, so they will attempt to eat as much of a given feed as is necessary to achieve that potential.

Getting the feed quality and feeding programme right is the trick, with decisions about this differing depending on the strain of broiler or layer used. In the case of broilers one has also to consider the way in which the birds are sold, the age or weight at which they are sold and the environment in which the birds are housed.

Financial implications also need to be considered: “It might not be profitable to ensure that all the hens in the flock are able to reach their potential because the cost of increasing the nutrient supply to that extent would almost certainly outweigh the benefits.

“There is an optimum economic level of feeding that ensures that the majority of birds in the flock are able to meet their potential. A small proportion of the flock won’t be able to do this, but they will come close enough to this potential to ensure that the profitability of the enterprise is maximised,” he said.

The nutritional and environmental requirements of broilers also change rapidly each day as they grow, making it impossible to feed these birds according to their changing demands each day. Only three or sometimes four feed regimes are used throughout the growing period, and in each phase the feed will be inadequate initially and then later become adequate and then surplus to their requirement, according to Prof Gous.

“The bird has to cope with this, and does so by initially overconsuming energy in its attempt to consume sufficient of the limiting protein in the diet. This excess energy intake is deposited as body fat.

“Later, as the protein content of the diet gets closer to, and then exceeds, the requirement, the bird will make use of these excess fat reserves as an energy source and will utilise this feed very efficiently until the next phase is introduced. The cycle repeats itself each time the feed is changed,” Prof Gous said.

Productive life

In the case of layer hens there is an optimum economic time to end the productive cycle. Gous explained that modern commercial layers have the potential to lay eggs at a much higher rate and to maintain that rate for much longer, than was the case a decade ago. The Hy-line W36, for example, is advertised as producing “more than 345 strong-shelled eggs up to 80 weeks of age.”

In spite of this, layers in certain countries, are being culled earlier than is generally the case in other countries. Prof Gous explained that this makes financial sense when there is a good market for spent hens

He said that the decision to keep layers to the end of their production cycle depended on various factors such as mortality, shell quality, rate of decline in rate of laying and most importantly the depreciation of the hen over time.

“In most countries, there is no value attached to culled hens, so the egg producer makes a huge investment in buying pullets at point of lay and gets nothing for them at the end of lay. The solution in that case is to keep the birds for as long as possible, even force-moult them and keep them for a second laying year,” Prof Gous said.

The problem with this is that hen numbers in the flock will be reduced over time because of mortality, some birds will stop producing for various reasons, and the rate of laying and shell quality will decline with time, all of which means that the profitability of the flock decreases with time. But having to replace those pullets is expensive, so the producer accepts the lower profitability over time.

In South Africa the situation is different: producers are able to sell spent hens at a reasonable price, which means that the depreciation on the flock is substantially reduced.

According to Prof Gous there is an optimum time to cull the flock and the lower the depreciation on replacing the flock the earlier this time becomes. It would not pay egg producers in South Africa to keep their hens longer than about 72 weeks of age.

Other developments

Lately there has been a demand for a slower growing breed of chicken from the Netherlands. Prof Gous said the demand was driven by a rising concern over animal welfare in that country.

The chicken, called the “kip-van-morgen”, may not grow faster than 50 grams per day, with production being subjected to very strict standards as far as stocking density, the use of antibiotics and bedding is concerned. The birds sell at about €1.46 per kilogram more than a standard broiler, according to Prof Gous, because of the lower stocking density and longer time spent in the broiler house, and the more expensive feed and greater feed usage.

Prof Gous feels that this is a retrogressive step that is only possible to comprehend in a wealthy population that can afford to pay so much more for what is perceived, by some, as being a more humane and bird-friendly environment in which to raise broilers.

For more information contact Prof Rob Gous at [email protected]

This article was originally published in the April 2016 edition of The Poultry Site Digital. For more, read other articles from the issue by clicking here.