Natural Ventilation in Organic Poultry Houses in Cold Weather

Winter ventilation and proper management in cooler ambient temperatures to control egg size in brown layers was the topic of Dr Morgan Hayes' presentation at the Midwest Poultry Federation Convention in St. Paul, Minnesota, US, writes Carla Wright, Editor, ThePoultrySite.

Most organic egg production in the US is from brown birds and these layers have an easy ability to lay very large eggs beyond what the industry can use.

“I

have seen up to 56-pound case weights and the industry struggles once case weight gets over 51 pounds. In cooler barn temperatures, brown birds eat more feed and this drives egg size higher. Once the bird

gets to a heavier case weight, it is almost impossible to bring it down even later on in summer.

Ventilation is one of the primary methods to control temperature, but there are some other

options,” says Dr Hayes, Post-doc Research Engineer with the USDA ARS, US Meat Animal Research Center in Clay Center, Nebraska.

How Natural Ventilation in Poultry Houses Works

Natural ventilation works based on the premise that fresh air is supplied based on natural

forces.

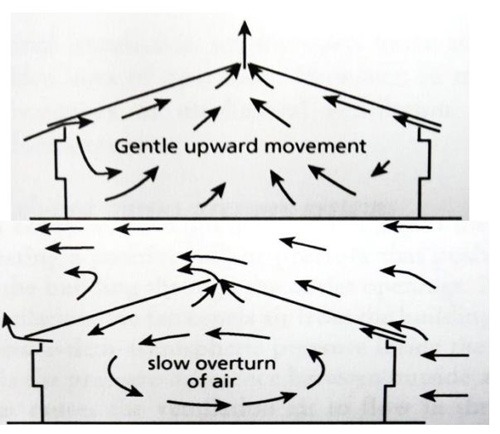

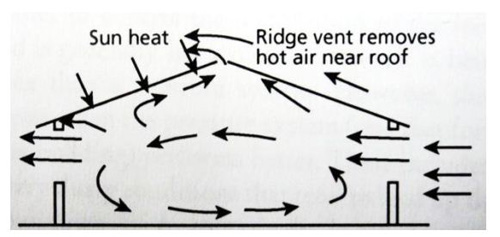

There are two types of natural ventilation: thermal buoyancy and wind-driven.

Buoyancy-driven ventilation is the primary method in winter months, because it results in less air being

exchanged, while wind provides summer ventilation due to more air exchanges.

However,

natural ventilation is difficult to manage for consistent indoor conditions due to its dependence on

the weather. Below are diagrams of ideal natural ventilation methods for winter (with and without

wind) and summer.

Thermal buoyancy driven ventilation works because hot air rises.

The birds in a naturally

ventilated barn produce heat, which in turn heats the air near the ground. That air rises and is

released through a ridge vent. Managing the area available for the air to enter and leave the barn

as well as the height between those openings can adjust the ventilation rate driven by thermal

buoyancy. The greater the opening or the greater the distance from inlet to outlet, the higher the

air exchange will be.

In the winter, when trying to maintain temperatures, limiting inlets and

outlets and keeping inlets closer to the ceiling will lower ventilation rates. If the air entering the

barn is further from the ridge, i.e. if the opening is on the floor where free-range birds move

freely in and out of the barn, the ventilation rate will be higher than it would be if the opening

were near the ceiling.

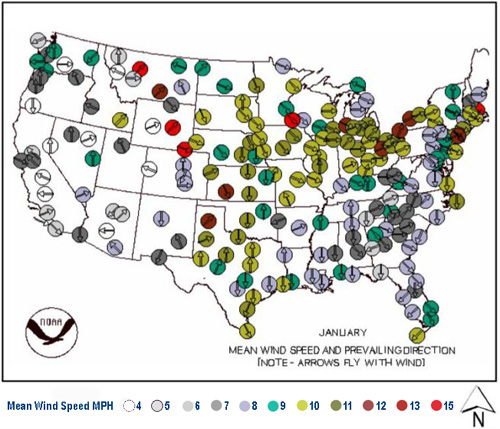

While buoyancy is ideal for winter ventilation, wind is a major concern because it can

easily increase ventilation. Wind-driven ventilation occurs when wind moves through an

opening. Wind speed and direction as well as the inlet and outlet areas affect the amount of

ventilation. Wind-driven ventilation will increase if there are larger openings on the windward

side of the barn.

Below is a map showing prevailing wind directions and speeds in January.

Much of the Midwest has wind from the northwest in the winter with average wind speeds greater

than ninemiles per hour. Leaving large inlets open greatly increases winter ventilation and will

cause cold draughts to reach the birds.

Ways to Limit Natural Ventilation

Natural ventilation is best managed by limiting inlet and outlet areas.

In the case of many

barns, the inlets are often a definite size because the birds use them to enter and leave the barns - the popholes.

These inlets near the floors are not ideal because of both the height to the outlet as well as the

possible cold draughty air reaching the birds.

If inlets can be placed so they are not on the windward

side of the barn in the winter, it is ideal. Outlets may be easier to close off, in order to lower

ventilation rates. A ridge vent runs along the length of the barns, but short sections may be able

to be closed off along the length.

A final consideration is to try to find and limit leaks in the barn;

these could be doors that are left open or curtain sidewalls that are not sealed.

Other Management Considerations

In addition to lowering ventilation rate, there are some other management opportunities for maintaining temperature. First, adding insulation to the barns, especially curtain walls and the roof may help. Insulation will keep the barn warmer and may prevent condensation.

Second, if the weather is extremely cold, it may be necessary to lock the birds in the barn or at the very least limit the hours of access to the outside. If the birds are outside in cold weather regardless of barn temperature, the birds will still eat more than desired. Third, if the barns remain cold with other management practices, it may be necessary to use supplemental heat.

Another option is that if

the birds’ weight gain and larger egg size are the only concerns with these winter temperatures,

there may be some dietary options for limiting the energy in the diet. Lowering the energy

content of the feed will prevent these larger eggs but will also potentially lower egg production

in the winter months.

March 2013