Understanding nesting behavior: Managing for fewer floor eggs in layers

Many egg markets have moved to more cage-free table egg production systems. In cage-free facilities the nesting behavior of hens is an important economic trait. Eggs that are laid outside of the nests are more likely to be contaminated by bacteria through increased contact with feces and litter. Outof-nest eggs are easily cracked, broken and eaten by other hens. The value of these eggs is lower due to downgrading and diversion to egg processing. The costly manual collection of eggs from the floor or within the aviary system is a nuisance to egg producers. Floor-laid eggs may lead to more cloacal cannibalism in the flock, which is a welfare issue.It is common for young layer flocks to lay some floor eggs as nesting behavior is established. Typically, the number of floor eggs will drop to a low level within 2–3 weeks. Floor eggs typically range from 1–4% for the life of a laying flock (4). In the field, the incidence of floor eggs depends on factors related to bird, environment, nest training, and management practices.

Nesting behavior in chickens

Understanding the normal nesting behavior of layers is important when developing appropriate management programs to minimize floor eggs. The nesting behavior of the hen is a complex interaction of genetic, behavioral, hormonal, and environmental factors. The laying hen’s environment should provide designated nesting areas that allow expression of the hen’s natural instincts to seek a nest for egg laying. Elimination of inappropriate nesting sites within the bird’s environment is the management challenge.

Pre-Laying Behavior

One to two hours before laying an egg, the hen will become restless and begin examining potential nesting sites as a part of the pre-lay ritual. A hen makes frequent nest visits before final nest selection, averaging 21.3 nest visits per egg laid (7). Between these nest examinations, the hen might eat, drink, and preen, as well as other behaviors (Figure 1). After selecting a site, the hen may turn around several times, exhibiting nest building behavior. If loose nesting material like sawdust is present, the hen spends more time nest building. Just before laying an egg, the hen extends the neck and body feathers. Some hens will stand to lay their egg. The time for the hen to lay an egg is highly variable between 10 and 90 minutes (7,11). After the egg is laid, the hen may vocalize (cackling) and want to sit on the egg for some time or just leave the nest.

The start of pre-laying behavior is triggered by the hen’s last ovulation (releasing the ovarian follicle into the oviduct) and not by the presence of an egg ready to be laid. The previous ovulation releases the hormones, estrogen and progesterone, which are responsible for the hen’s pre-laying behavior (1). Any stressful event eliciting a fear response could cause the hen to suspend nest selection and delay egg laying. If the pre-laying stimulus passes before the egg is laid, then the hen may lose interest in seeking a nest, resulting in more eggs laid on the floor.

Pecking Order

During the rearing period, the social hierarchy of dominant/submissive relationships between individuals in a group of birds is established. High ranking birds have first access to food, water, and nesting sites. High ranking, dominant hens will occupy preferred nesting sites to the exclusion of lower ranking hens. If the number of preferred nesting sites is limited, then submissive hens might be forced to seek alternative nesting sites, resulting in more out-of-nest eggs.

Nest Preference

Hens prefer nests that are dark, secluded, warm, and comfortable. Nests containing loose material, such as wood shavings, rice hulls or straw are preferred and hens express more nest building behaviors. In cage-free commercial production systems, it is common to utilize automatic egg collection nests, with a rubber (plastic) nest floor mat or artificial turf. Hens show a preference of solid nest floors over wire nest floors (13). Hens prefer nests located in corners or at the end of the line. Nests in elevated locations are generally preferred compared to ground level nests (8). Young, inexperienced hens may prefer nests that are occupied by other hens (gregarious nesting) (1); this behavior tends to lessen with bird age (Figure 2). In aviary systems, hens will choose more isolated nests located along the wall before utilizing nests located within the aviary rack (6).

Nesting is a learned behavior, but once established in a hen, it becomes difficult to change. Hens tend to return every day to the same nesting sites. Consistent nest layers and floor layers can be identified in a flock (3). The management challenge for egg producers is to make the designated nests attractive to hens and eliminate alternative nesting sites where hens might lay out-of-nest eggs

Factors affecting the incidence of floor eggs

Bird Behavior

- Nest training

- Dominant hens or roosters prevent subordinate hens from reaching nesting sites

- Gregarious nesting behavior, especially in young layers

- Overcrowding in corner and end of the

- line nests

Facility design

- Hens’ movement to nests is blocked by waterlines, feeders or enrichments

- Litter depth

- Elevation changes not properly ramped

Nests

- Insufficient number of suitable nesting sites

- Nests located in areas with more mechanical noise or vibration

- Worn nest floor mats, making nests uncomfortable

- Dirty or malodorous nests. This can occur when nests are not closed at night or are soiled with egg contents.

- Interior of nest too bright

Environment

- Overcrowding of birds, blocking movement toward nests

- Uneven ventilation, causing nests to be too cold and drafty. In summer, uneven ventilation may cause some nests to be too hot with stale air.

- Uneven light distribution

- Heat stress

- Stray voltage (new construction, recent electrical repairs)

Feed Management

- Running feeders during peak nesting time, attracting hens away from the nests

- Use of grit, feed formulations with high fiber to increase foraging behavior

Bird Health

- Leg problems from infections (Staphlyococcus, Enterococcus, Mycoplasma synoviae)

- Injuries during handling, transfer or within the aviary system

- Nests infested with insects (red mites, northern fowl mites, fleas, ticks)

- Nests infested with rodents

Hy-Line’s selectiopn program for good nesting behaviour

Cage-free traits have moved to the forefront of Hy-Line International’s breeding program. Nesting behavior as it impacts the incidence of floor eggs may be the most important cage-free trait. Hy-Line International has been selecting against floor eggs for more than a decade. The genetic determination of this trait and an estimate of its heritability in commercial lines has been established (10). Nesting behavior has been measured by observing the incidence of floor eggs in pen production of all versions of Hy-Line Brown male lines. Birds are evaluated under challenging conditions. Sire breeding values are predicted to select families that are less prone to lay out of the nest. A new approach uses up-selected males with better breeding values for nesting behavior in pen matings and only utilizes hatching eggs from hens with good nesting behavior. This new approach is being used to produce male lines for cagefree markets. In addition, new approaches are being tested to identify nesting behavior of individual females (instead of sire families), to separate consistent nest users from hens that prefer laying on the floor. These new approaches include trap nesting hens in aviary-like systems; wearing Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) transponders to study nest usage and behavior; and a biological approach that combines laying behavior phenotypes with genomics to identify hens that lay in the nest. Breeding efforts have resulted in a reduction of the genetic predisposition of hens to lay their eggs on the floor.

Management considerations during rearing

Training

Training hens for good nesting behavior begins during their rearing period. If hens will have to jump up to reach the nests and perches during the laying period, then jumping behavior should be habituated during the rearing period.

Feeders, water systems, and perches used during rearing and laying should be matched. Pullets reared in aviary systems adapt faster after transfer to aviary laying facilities, with fewer floor eggs than floorreared pullets (2).

Water Tables

In addition to perches, birds reared primarily on the floor should have water tables. In none aviary houses, water tables (Figure 3, elevated platform) should be under 100% of all water lines so birds have to jump to drink. This setup helps birds learn to look for what they need (feed, water, nests) in vertical as well as horizontal environments.

Perches

Perches and elevated water platforms should be present in the rearing flock by 10 days of age to establish jumping behavior in the young pullets and develop strength in leg and breast muscles. Perches provide a safe resting space for birds and lowers the density of birds on the floor. The ability of pullets to use perches will be important later for accessing elevated nests. Hy-Line's internal research has found negative genetic correlation between perch use and nesting behavior (manuscript pending publication). The type of perches used in rearing should be the

same design and material as those to be used during the laying period (Figure 3). Perches should be placed on the slats when using a litter (scratch area)/slat flooring. The perches should support the bottom of the bird’s foot and be easy to grip. Do not use electric deterrent wire over water or feeder lines, as this will discourage jumping behavior in pullets

Management considerations during transfer

Transfer pullet flocks to the laying facility by 16 weeks of age, or a minimum of 14 days before first eggs. This provides the birds sufficient time to adapt to the new laying environment and to re-establish the pecking order. In laying facilities utilizing litter and elevated slat areas, the pullets should be transferred onto the slats. It is important that the hens use the aviary system for roosting during the night. Any hens on the litter at dusk should be manually placed in the aviary system (Figure 4). The nests should be open and available for examination by hens at housing. Lifting every third or fourth nest flap will encourage nest exploration. Run the egg belts during the day to accustom hens to the noise and vibration of this equipment.

Management considerations during the laying period

Training Period

The nest training period begins from transfer until the flock reaches the peak of egg production(around 27–32 weeks). During this time, the young layer should learn to consistently use the provided nests.

In the training period, the flock manager should walk in the flock a minimum of six times each day, starting from the opposite side of the nest area. During these walks, the birds should be stimulated to get up and move away from the walls, out of corners and toward the nests. Any floor eggs should be picked up immediately and any hens observed nesting outside of the provided nests should be gently placed inside a nest. The presence of a few eggs in the nests will attract hens to visit the nest. Observe where floor eggs are being laid and devise a plan to make these locations less attractive for nesting.

During nest training, leave the floor free of obstacles that might block the movement of hens to the nests, such as pecking blocks or lucerne (alfalfa) bales. These enrichments can be suspended above the floor or introduced after the training period (Figure 5). The hens’ path to the nests should be clear of blockages, such as low water lines and feeders.

Keeping the house temperature around 20–21°C (68–70°F) or lower, with good air movement, keeps the hens active and discourages floor eggs.

Nest Opening and Closing

Automatic nests should be opened two hours before lights on, and closed two hours before lights off. When using dawn/dusk sequential lighting, the nests can be opened two hours before the beginning of the dawn light sequence. Nest closing can be one hour before the dusk lighting sequence. The last feeder run should be scheduled just prior to nest closing to pull hens out of the nests that may otherwise be settling in for the night.

Eliminating Alternative Nesting Sites

Corners of any kind are common locations in which to find floor eggs. Rounding these corners will make them less desirable as nest sites. Along a wall is another common location for floor eggs. Shaded areas under feeder troughs, feed hoppers, feeder motors, pan feeders, bell drinkers, and environmental enrichments may attract hens to lay on the floor (Figures 6–9). Supplemental lights can be added in areas where shadows exist. String lights work well for this application (Figure 10).

Electric Deterrent Wires

Electric deterrent wires, where they are permitted, can be an important tool to prevent floor eggs. Deterrent wires should be positioned to keep birds away from the walls and pen partitions, and out of the corners. Activate deterrent wires as soon as the flock is transferred to the laying facility. Deterrent wires are especially effective during the nest training period and may be turned off after the hens are consistently using the nests (Figure 11).

Nest Usage

Calculations for nest space assumes that all nests will be used by the flock. Often this does not occur and only a percentage of the total nests are used by the hens. When this occurs, partition the flock into smaller bird groups to force more uniform bird distribution. Hens may prefer corner and end of the line nests, causing overcrowding in these nests. Placing false walls between the nests might alleviate the crowding in these areas (Figure 12).

Egg Collection

The majority of eggs are laid 1–5 hours after the house lights are turned on. This corresponds to the time of peak nest occupancy (6,7,8 and 9). Egg collection should begin after the majority of the hens have gone to the nests. To avoid disturbing nesting hens, the egg belts should not be run during the time of peak egg laying. If it is necessary to run the egg belts, do so at a low speed to reduce the noise and vibration of the equipment.

Litter

Litter is an attractive nesting material for hens and encourages nest building behavior. When using litter on floors, the depth should be less than 5 cm (2 in) to discourage nesting in the litter. Build up to this level gradually with minimal depth during nest training. Periodically rake the litter to prevent areas of deep litter, where hens might be attracted to lay eggs.

Ventilation

Poor ventilation can contribute to hens rejecting a nest site. Nests located near fans or facing air inlets might become too drafty and cold. Tunnel ventilated houses during the summer season may not move enough air inside nests, causing them to be too hot.

Nest design

Nest Space

In automatic egg collection colony nest systems, provide 1 m² (10.8 ft²) of nest floor space per 100–120 hens (83.3–100 cm/32.8–39.4 in per hen) or 40 hens per linear meter of open space at the front of the nest. For manual egg collection, nest boxes should provide one nest per six hens. Check local regulations regarding nest space.

Nest Design

The nests should be designed to provide a safe and comfortable environment with easy access. The perches and landing platforms in front of nests should be easy to access and traverse (Figure 13). If hens have to jump to access the nests, the vertical height is ideally 65 cm (25.6 in), but not exceeding 90 cm (35.4 in)(Figure 14).

Use ramps and broad landing platforms to provide easy access to elevated nests (Figure 15). Hens made fewer balance movements with 60 cm (23.6 in) width platforms compared to 30 cm (11.8 in) platforms, with less aggressive behavior between hens. Hens prefer a grid floor platform to wooden slats (6).

Commercial automatic egg collection group nests used in cage-free facilities are common. Typically, each nest has a floor surface area ranging from 0.5 to 1.8 m2 (5.4 to 19.4 ft2), with a relatively constant depth of 0.5–0.6 m (1.6–1.97 ft) and a width of up to 3 m (9.84 ft).

Hens show a preference for smaller group nests (0.72 m/2.36 ft width x 0.6 m/1.97 ft depth) compared to larger nests (1.44m/4.72 ft width x 0.6 m/1.97 ft depth), based on more eggs laid in the smaller nest with fewer nest visits per egg (9). Hens prefer group nests with non-transparent flaps covering the nest entrance compared to open nests. Nest flaps cut into strips are preferred over nests with one whole flap (12).

Slope of Nest Floor

In automatic colony nests, the nest floor is sloped to allow the rapid roll-out of eggs from the nest onto the egg belt. Nest floors that are excessively sloped may not be comfortable, causing hens to seek alternative nesting sites outside of the system. Commercial colony nests with automatic egg collection generally provide nest floors with 12% to 18% slope. This range is widely accepted by laying hens, but there may be a hen preference for 12% compared to 18% (11).

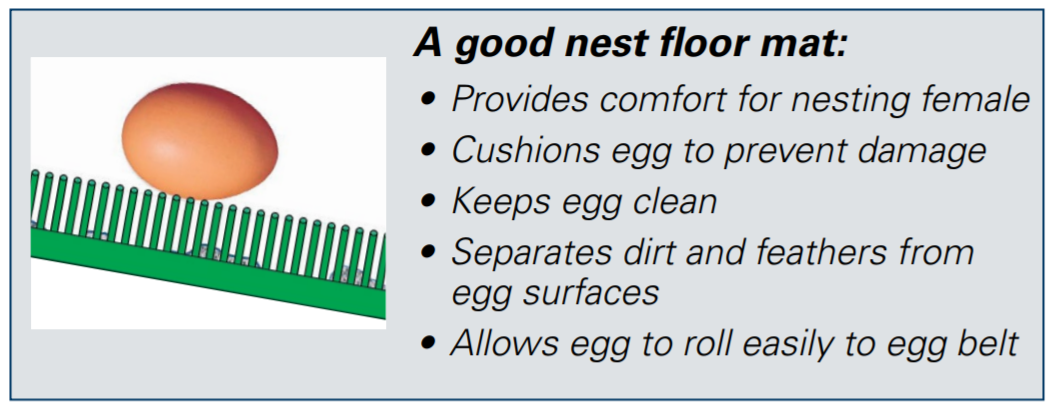

Nest Floor Mats

Clean and sanitize nest floor mats between flocks. Replace worn nest floor mats to keep nests comfortable for the nesting hens. Good nest floor mats ensure that eggs are gently rolling out of the nest onto the egg belt (Figure 16). Worn mats cause eggs to be retained in the nests and allow hens to sit on eggs, resulting in more cracked eggs and more aggression toward new entrants.

Egg Belts

Egg belts should be cleaned regularly and, if damaged, replaced between flocks. Egg belts that have been soiled with broken eggs may give the nest an objectionable smell, causing the hens not to use the nests. In automatic nests, the brushes that hide the egg belt from view of nesting hens may become worn, revealing the moving egg belt. Hens can be disturbed by the movement of egg belts and leave the nest. Not running the egg belts during the peak egg laying times can mitigate this problem.

Lighting problem

Distribution of Light

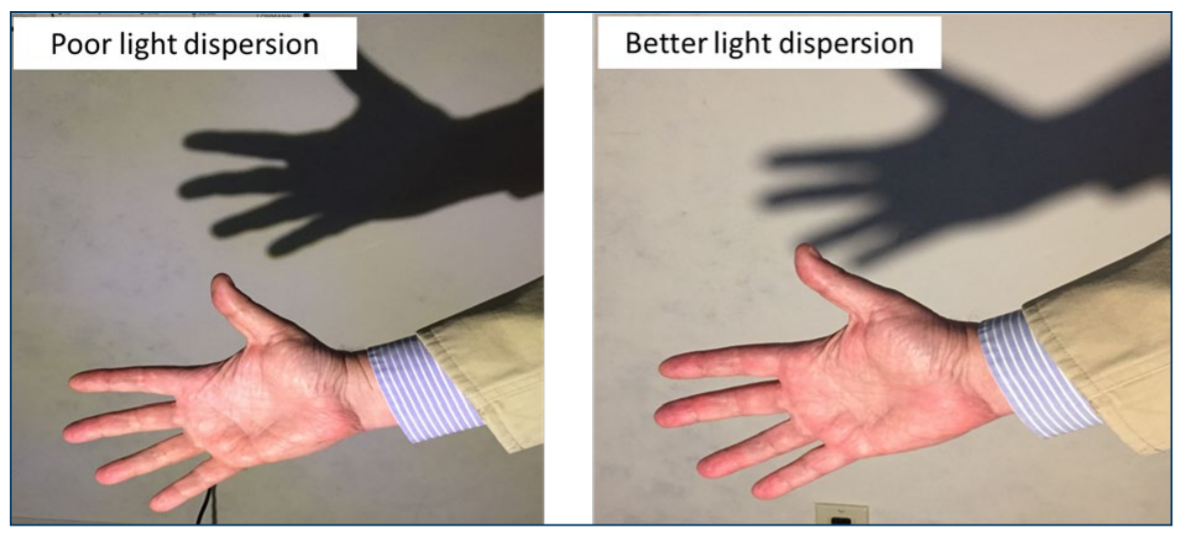

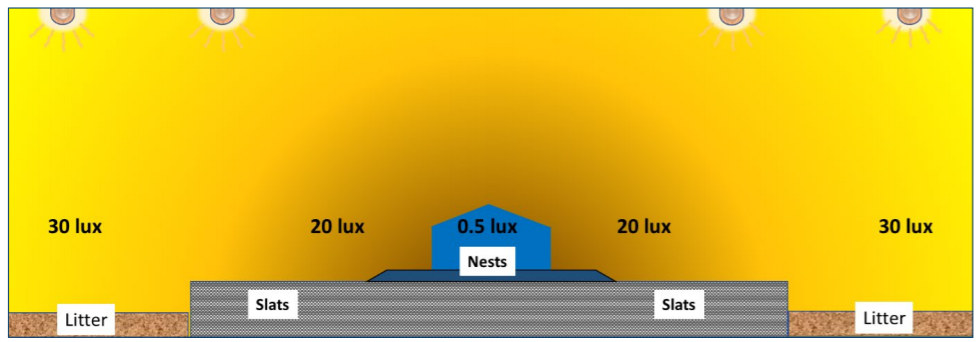

Place lights to eliminate any shadows in the activity, feeding and drinking areas in the bird’s environment. One or two rows of lights positioned in an alternating pattern usually creates the most uniform light distribution. Use a light source that produces diffused light and does not create shadows. Some LED light sources produce directional light that produces sharp areas of shadow under feeders, water lines, and in corners (Figure 17). The brightest area in the house should be in the activity area where birds eat, drink and rest. The entrance to nests should be well-lit, but not brighter than the activity area. The inside of the nests should be dark, preferably less than 0.5 lux (Figure 18)

Simulation of Dawn and Dusk

In aviary systems, the house lights are typically stepped/sequenced to draw the birds up onto the system at night. Any birds that remain on the floor should be lifted and manually placed in the system. Not permitting hens to spend the night on the floor can reduce floor eggs.

Nest Lights

String LED lights placed inside automatic colony nests can be used to attract hens to the nests in the morning. Nest lights are typically turned on one hour before and turned off one hour after the house lights come on. Nest lighting can be especially effective during the nest training period. Nest lights can be discontinued after the hens are consistently using the nests.

Timing of Lights-on

If floor eggs are encountered, it is important to determine what time of day they are being laid. In houses that are not fully light-proof, the outside light, particularly in summer months, may cause birds to lay before house lights are switched on. In this instance, house lights should be programmed to come on earlier.

Feeding considerations

Feeding Schedule

Schedule the automatic feeder runs not to interfere with the pre-laying behavior and egg laying of the flock. Typically, the first feeder run is timed when the house lights come on in the morning, or alternatively, just before the house lights turn on. The second feeding is after the majority of eggs have been laid. Poorly timed feeder runs can interrupt pre-laying behavior and motivate hens to leave the nests, resulting in more floor eggs. Preferably, place all feeders on the slats when using a combination of litter (scratch) and slats. Adjust feeder and water lines to the proper height to avoid creating obstacles for hen movement to the nests. Prevent swinging water lines that could distract nesting hens. Provide sufficient feeder space and use fast feeder run times (18 meters /min feeder) to ensure that all hens can eat simultaneously.

Considerations for breeding flocks

In breeder flocks, eggs laid outside the nests are not suitable for hatching and cause significant economic loss. These eggs are often soiled with feces and dirt, leading to bacterial contamination of the egg and hatchery. Hatchability and chick quality are decreased if out-of-nest eggs are used for hatching.

The proper ratio of roosters to hens should be set by 16 weeks of age. See Hy-Line Parent Stock Management Guides (www.hyline.com) for the recommended ratios for each genetic variety. Too many roosters result in excessive fighting as they establish territories and compete for females. This can lead to males acting aggressively toward females and disrupting their normal nesting behavior. Roosters may attempt to “corral” hens, blocking their movement to the nests. Low-ranking males often hide inside the nests to avoid persecution by dominant males. The presence of males inside the nests may result in females refusing to use these nests. Low-ranking males without tail feathers, small combs, or appearing pecked and underweight should be continuously culled from the flock.

Summary

Nesting behaviors are habituated in the hen soon after egg production begins and, once established, become difficult to change. Manage the flock to provide positive early nesting experiences, leading to good nesting behaviors. Eliminate obstacles, interruptions, and negative experiences that might cause hens to lay out-of-nest eggs.

| References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Appleby, M. C., 1984. Factors affecting floor laying by domestic hens: A review. World’s Poultry Science Journal. 40:241–249. | ||||

| 2. Colson, S., Arnould, C., Michel, V. 2008. Influence on rearing conditions of pullets on space use and performance of hens placed in aviaries at the beginning of the laying period. Applied Animal Behavior Science, 111: 286–300. | ||||

| 3. Cooper, J.J., Appleby, M.C., 1995. Nesting behavior of hens: Effects of experience on motivation. Applied Animal Behavior Science, 42: 283–295. | ||||

| 4. Icken, W., Thurner, S,. Heinrich, A., Kaiser, A., Cavero, D., Wendl, G., Fries, R., Schmutz, M., Preisinger, R. 2013. Higher precision level at individual laying performance tests in noncage housing systems. Poultry Science, 92 (9): 2276–2282 | ||||

| 5. Karin S., Roth, B.A., Buchwalder, T., Fröhlich, E.K.F. 2011. Influence of nest-floor slope on the nest choice of laying hens. Applied Animal Behavior Science, 135: 286–292. | ||||

| 6. Lentifer, T.L., Gebhardt-Henrich, S. G., Fröhlich, E. K., von Borell, E. 2011. Influence of nest site on the behavior of laying hens. Applied Animal Behavior Science, 135 (1): 70–77. | ||||

| 7. Oliveira, J., Hongwei X., Zhao, Y., Li. L., Liu, K., Glaess, K. 2016. Nesting behaviors and egg production pattern of laying hens in enriched colony housing. Iowa State University Digital Repository: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu | ||||

| 8. Riber, A. B., 2010. Development with age of nest box use and gregarious nesting in laying hens. Applied Animal Behavior Science, 14: 75–88. | ||||

| 9. Rinnenberg, N., Fröhlich, E.K.F., Harlander-Matauschek, A., Würbel, H., Roth, B.A. 2014. Does nest size matter to laying hens? Applied Animal Behavior Science: 155, 66–73. | ||||

| 10. Settar, P., Arango, J., Arthur, J. A. 2006. Evidence of genetic variability for floor and nest egg laying behavior in floor pens. XII European Poultry Conference. Verona, Italy.10–14 September, 2006. Comm. 58 http://www.cabi.org/animalscience/worlds-poultry-science-association-wpsa/wpsaitaly-2006/ | ||||

| 11. Buchwalder, T., Fröhlich, E.K.F. 2011. Influence of nest-floor slope on the nest choice of laying hens. Applied Animal Behavior Science, 135: 286–292. | ||||

| 12. Struelens, E., Buchwalder, T., Fröhlich, E.K.F, Roth, B.A. 2012. British Poultry Science, 53: 553–560. | ||||

| 13. Struelens, E., Van Nuffel, Tuyttens, F.A.M., Audoorn, L., Vranken, E., Zoons, J., Berckmans, D.,Ödberg, F., Van Dongen, S., Sonck, B. 2008. Influence of nest seclusion and nesting material on prelaying behavior of laying hens. Applied Animal Behavior Science, 112: 106–19. | ||||