Tiny Animals Aid Salmonella

US - Salmonella, one of the planet's most problematic food-poisoning bacteria, may have an accidental ally: transparent, nearly invisible animals called protozoa. Agricultural Research Service microbiologist Maria T. Brandl has provided new evidence of the mostly mysterious interaction between these microscopic protozoa and Salmonella.

Tiny Animals Aid Salmonella - US - Salmonella, one of the planet's most problematic food-poisoning bacteria, may have an accidental ally: transparent, nearly invisible animals called protozoa. Agricultural Research Service microbiologist Maria T. Brandl has provided new evidence of the mostly mysterious interaction between these microscopic protozoa and Salmonella.

During their lives, Salmonella bacteria may encounter a commonplace, water-loving protozoan known as a Tetrahymena. Brandl's laboratory tests showed that the protozoan, after gulping down a species of Salmonella known as S. enterica, apparently can't digest and destroy it. So, the Tetrahymena expels the Salmonella, encased in miniature pouches called food vacuoles.

The encounter may enhance Salmonella's later survival. Brandl found that twice as many Salmonella cells stayed alive in water if they were encased in expelled vacuoles than if they were not encased.

What's more, Brandl found that the encased Salmonella cells were three times more likely than unenclosed cells to survive exposure to a 10-minute bath of two parts per million of calcium hypochlorite, the bleachlike compound often used to sanitize food and food-processing equipment.

The research is the first to show that Tetrahymena expel living S. enterica bacteria encased in food vacuoles and that the still-encased, expelled bacteria can better resist sanitizing.

Brandl and colleagues Sharon G. Berk of Tennessee Technological University-Cookeville and Benjamin M. Rosenthal at ARS' Henry A. Wallace Beltsville (Md.) Agricultural Research Center documented their findings in a 2005 issue of Applied and Environmental Microbiology. Brandl now wants to pinpoint genes that Salmonella bacteria turn on while inside the vacuoles. Those genes may be the ones that it activates when invading humans.

Source: USDA Agricultural Research Service - 16th February 2006

Brandl's discoveries from her work at the agency's Western Regional Research Center in Albany, Calif., may lead to new, more powerful, and more environmentally friendly ways to reduce the incidence of Salmonella in meat, poultry and fresh produce.

|

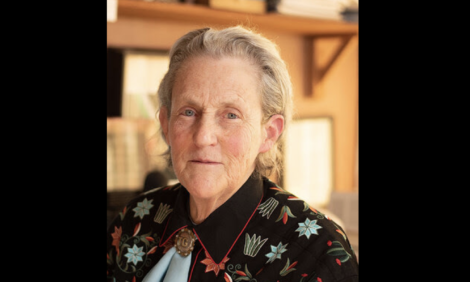

| Microbiologist Maria Brandl views microscopic Tetrahymenaprotozoa growing in a liquid medium. |

The encounter may enhance Salmonella's later survival. Brandl found that twice as many Salmonella cells stayed alive in water if they were encased in expelled vacuoles than if they were not encased.

What's more, Brandl found that the encased Salmonella cells were three times more likely than unenclosed cells to survive exposure to a 10-minute bath of two parts per million of calcium hypochlorite, the bleachlike compound often used to sanitize food and food-processing equipment.

The research is the first to show that Tetrahymena expel living S. enterica bacteria encased in food vacuoles and that the still-encased, expelled bacteria can better resist sanitizing.

Brandl and colleagues Sharon G. Berk of Tennessee Technological University-Cookeville and Benjamin M. Rosenthal at ARS' Henry A. Wallace Beltsville (Md.) Agricultural Research Center documented their findings in a 2005 issue of Applied and Environmental Microbiology. Brandl now wants to pinpoint genes that Salmonella bacteria turn on while inside the vacuoles. Those genes may be the ones that it activates when invading humans.

Source: USDA Agricultural Research Service - 16th February 2006