Congessional Hearing Examines Welfare Of Farm Animals

WASHINGTON - Witnesses from the AVMA and other organizations testify about current concerns

Several veterinarians were among a dozen witnesses who testified before the Subcommittee on Livestock, Dairy, and Poultry about improving the welfare of farm animals while protecting the food supply, consumer choice, and biomedical research.

The subcommittee chairman, Rep. Leonard L. Boswell of Iowa, noted in his opening remarks that restaurants are requiring suppliers to meet certain animal welfare standards, and consumers are paying more for products such as cage-free eggs. He said these voluntary changes might or might not be sufficient to fix the problems that some people perceive to exist in animal agriculture.

The ranking minority member, Rep. Robin Hayes of North Carolina, responded that animal agriculture has made great strides in addressing welfare. He then questioned the timing of the hearing because he does not believe that the Farm Bill should include animal welfare.

The hearing also pertained to other pending federal legislation, particularly a ban on slaughtering horses for human consumption and legislation to prevent nonambulatory animals from entering the food supply.

Emotions ran high during opening testimony and question-and-answer periods. Congressional representatives grilled those witnesses advocating for legislative changes about extremist tactics, vegetarianism, and movements against keeping animals at all.

Throughout the hearing, discussion covered general welfare concerns as well as species-specific issues.

AVMA testimony

Dr. Gail C. Golab, associate director of the AVMA Animal Welfare Division, testified that animal welfare is of primary importance to the veterinary profession.

"This hearing will highlight differences that exist among stakeholders with regard to how we believe animals should be used and cared for," Dr. Golab said. "An important underlying truth is that most people in the United States believe it is acceptable to use animals for food and fiber, as long as the welfare of those animals is good."

Dr. Golab said producers and activists do not generally agree on what constitutes good welfare, though. Producers tend to cite elements of good health and performance as evidence of good welfare, while activists are more comfortable when animals live in natural environments.

The AVMA believes no assessment of animal welfare is complete without scientific consideration of all the elements, Dr. Golab said. One cannot judge the welfare of an animal on the basis of physical health without regard for suffering or frustration, and one cannot conclude that an animal able to engage in species-typical behavior has a good state of welfare without also evaluating health and biologic function.

|

| Dr Gail C. Golab associate dirctor of the AVMA Animal Welafre Division, testifies during a congessional hearing on animal welfare. At left is Wayne Pacelle of The Humane Soiciety of the United States, and at right are Dr Steven L.Leary of the National Association for Biomedical Research and Gene Gregory of the United Egg Producers |

"Pulling together societal expectations and industry needs means that guidelines for animal care must be both science-based and dynamic," Dr. Golab said. "Common sense and science depend on each other to reach sound conclusions on animal welfare."

Animal activists

Wayne Pacelle, president of the Humane Society of the United States, opened his testimony by responding to criticisms of animal activists. He said some people caricature the entire cause of animal protection.

Pacelle testified that the HSUS works against practices that are out of step with prevailing public sentiment. His examples included gestation stalls for pregnant sows, nonambulatory animals in the food supply, and horse slaughter for human consumption. He said bans on these practices would not have apocalyptic consequences for agriculture.

Almost no federal legislation covers the welfare of farm animals, Pacelle said, other than the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act. He spoke in favor of the Farm Animal Stewardship Purchasing Act (H.R. 1726), which would bar the federal government from purchasing products from animals in intensive confinement. He also spoke in favor of including animal welfare in the Farm Bill.

Gene Baur, president of Farm Sanctuary, said the push to produce more food, more cheaply, has led to a view of animals as commodities. In some instances, Baur said, animal welfare can be in conflict with animal production.

Baur's examples included gestation stalls and the disposal of male chicks at hatcheries that produce laying hens. Baur noted that the federal Animal Welfare Act does not cover farm animals, except for research purposes.

Research, consumer choice

Dr. Steven L. Leary, assistant vice chancellor for veterinary affairs at Washington University in St. Louis, testified for the National Association for Biomedical Research.

"Animal research has played a vital role in virtually every major medical advance of the last century, for both human and animal health," Dr. Leary said.

Dr. Leary said most people agree with using laboratory animals in research that will help alleviate suffering from a serious disease. The Animal Welfare Act provides for the proper care and treatment of laboratory animals, he said.

David Martosko, director of research for the Center for Consumer Freedom, urged congressional representatives to be skeptical of organizations that propose to extend human rights to animals.

Martosko said animal rights organizations such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals discourage Americans from eating meat, no matter how humanely producers raise farm animals.

Martosko went on to ask why animal welfare activists should be able to prevent him from eating specific meat products, such as foie gras or veal.

Horse industry

Former Rep. Charles Stenholm of Texas testified on behalf of animal agriculture, but he also answered questions about horse slaughter as a current representative of the Horse Welfare Coalition. The coalition, which counts the AVMA among its members, opposes banning horse slaughter.

Exports of horse meat add more than $30 million to the economy, Stenholm said. He said the movement to halt horse slaughter is costing jobs, too.

Stenholm said horse owners have the right to dispose of their personal property, like other livestock owners. He noted that other countries don't regulate humane methods of slaughter the same way as the United States. He added that banning horse slaughter doesn't address unwanted horses.

Leslie Vagneur Lange, national director of the American Quarter Horse Association, testified that the AQHA does not prefer slaughter as a way of dealing with unwanted horses. The organization's board believes processing is currently a necessary aspect of the equine industry, though.

Without horse slaughter, Lange said, owners will not have a way to sell horses that they no longer want or cannot afford to keep. Owners might then abandon or starve the horses. Banning slaughter could lead to tens of thousands of horses annually overwhelming the far too few rescue facilities.The horse industry helped form the Unwanted Horse Coalition to work toward eliminating unwanted horses, Lange said.

Poultry industry

Gene Gregory, president of the United Egg Producers, testified that the UEP recognizes animal welfare is of increasing importance to retailers and consumers.

In 1999, the UEP commissioned a scientific advisory committee to review the organization's standards on animal welfare. Today, about 85 percent of egg producers have implemented changes that the committee recommended—including an increase in cage space.

The committee's recommendations are the basis of the UEP Certified Program. Participating producers are subject to annual audits and may place a seal on their egg cartons if they adhere to the guidelines.

Gregory added that the UEP disputes the proposition that only cage-free production is humane. Cages protect birds from predators and diseases, he said, and cages might reduce aggressive behavior.

Guillermo Gonzalez, owner of Sonoma Foie Gras, testified on behalf of the Artisan Farmers Alliance, a new organization that represents the three U.S. farms that produce foie gras.

Foie gras is the fatty liver of ducks and geese resulting from force-feeding. Gonzalez said studies have not found the method to create abnormal stress in ducks.

Gonzalez said producers of foie gras believe the public should be able to choose whether or not to eat the product, but activists are trying to ban the sale of the product in many jurisdictions.

Swine industry

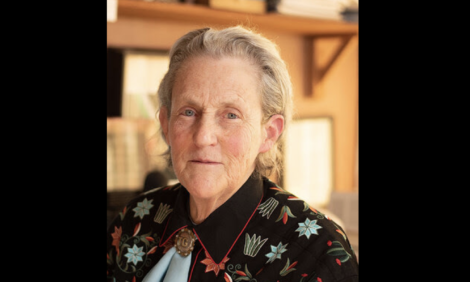

|

| Dr. Gail. C. Golab associate dirctor of the AVMA Animal Welfare Association |

Barbara Determan, past president of the National Pork Producers Council, testified that America's pork producers raise their pigs humanely out of moral obligation and to protect their livelihood.

In 1989, producers established the Pork Quality Assurance certification program. Producers later developed the Swine Welfare Assurance Program, an educational and assessment tool. The PQA Plus program debuts this year as a combination of PQA and SWAP with an audit component.

Determan added that the pork industry believes gestation stalls and group housing both provide for the well-being of sows during pregnancy, with each system having advantages and disadvantages. She said mandating any one type of sow housing or changing simply for the sake of change is not necessarily in the best interest of the pig.

Determan said producers do not believe Congress has the expertise to decide which on-farm practices are best for animals, including approaches to antimicrobial use. She said the pork industry has created a program to enhance producer awareness about antimicrobial resistance.

In response to a question about nonambulatory animals, Determan testified that pigs sometimes do lie down after transport upon arrival at the slaughterhouse. With time to rest, most pigs will stand again and are safe to enter the food supply.

Cattle industry

Paxton Ramsey, a member of the National Cattlemen's Beef Association, began his testimony by painting a picture of cowboy life. He said cattlemen, by second nature and out of business sense, maintain a long-standing commitment to the health and welfare of their animals.

In 1987, the NCBA created the Beef Quality Assurance program, which now influences more than 90 percent of U.S. cattle. The BQA program encompasses the Producer Code of Cattle Care. In 2003, the cattle industry expanded on the code with the Guidelines for the Care and Handling of Cattle.

Dr. Karen Jordan, owner of Large Animal Veterinary Services in Siler City, N.C., testified on behalf of the National Milk Producers Federation. Dr. Jordan and her husband own a dairy farm.

"Simply put, what's good for our cows is good for our business," Dr. Jordan said.

In 2002, NMPF and the Milk and Dairy Beef Quality Assurance Center developed the Caring for Dairy Animals Technical Reference Guide. The quality assurance center also offers an audit program.

Additionally, the dairy industry has addressed care of replacement heifers and veal calves. Farmers who raise replacement heifers can refer to Raising Quality Replacement Heifers. The American Veal Association has developed the Veal Quality Assurance Program.