The Home Flock

By Tom W. Smith and Robert L. Haynes, Extension Poultry Science specialists, Mississippi State University - The "home flock" usually consists of 20 to 40 chickens kept to supply eggs and an occasional fat hen. An average family of five persons will require about 30 hens. To produce 30 pullets, start with 100 straight-run chicks or 50 sexed pullet chicks. You should purchase pullet chicks only if you want layers.Start with Healthy Chicks

You can start chicks at any time during the year. Baby chicks started in March or April are normally the easiest to raise up to laying age (6 months). The problem with starting birds then is that they begin production in late summer or early fall. Birds started in March or April generally do not lay as many total eggs as do birds started in November and begin production in April. The disadvantage of starting birds in November is that they are harder to raise through the winter months to laying age in April.

Usually the most desirable birds for a small flock are dual-purpose breeds such as Rhode Island Reds, Barred Rocks or Plymouth Rocks. However, if you are to keep birds for egg production only, it is best to choose birds bred only for that purpose (White Leghorn or Leghorn crosses). Choose chicks reared for slaughter as broilers from one of the commercial broiler strains. The commercial broiler strains have been developed by genetic selection for high meat producing traits.

Chicks being reared for broiler production should be debeaked at the hatchery or when first placed in the growout facility. The chicks being reared for egg production should be debeaked at 7 to 10 days of age to avoid problems in the rearing and laying house. Debeaking is the removal of the upper and lower beaks by means of a heated cutting and cauterizing blade. Debeaking helps primarily to prevent cannibalism but also helps to reduce feed wastage. The chicks should also be vaccinated in the hatchery for Marek's disease and at four days old for Newcastle disease and bronchitis.

Prepare the Brooding House

Be sure the brooding area is prepared well in advance of the chicks' arrival. Allow one square foot of floor space per chick. The brooding house should be dry and provide the chicks with protection from cold or rainy weather. It should be well ventilated but free from drafts. The house should allow easy access to electricity and water and should prevent entry by rats, dogs, cats, and wild animals.

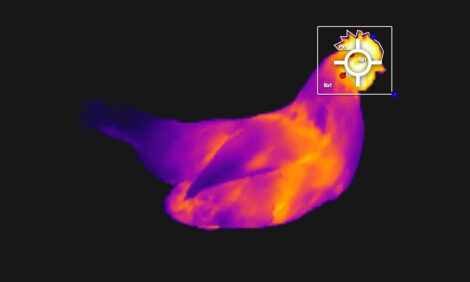

The brooder is an artificial mother to the chicks and provides warmth to keep them comfortable during the first four to six weeks. Two common types of brooders are infra-red heat lamps and the hover-type, gas fired brooders.

Thoroughly clean and disinfect the brooding area and equipment at least two days before the chicks arrive. After the area has dried thoroughly, cover the floor with 4 to 6 inches of dry litter material. Pine wood shavings or sawdust is recommended. Hardwood litter allows the growth of fungus-type organisms that can cause a poultry disease called aspergillosis or brooder pneumonia. Pine wood litter helps restrict the growth of the disease-causing organisms.

Turn on the brooder and adjust it to the proper temperature at least 4 to 6 hours before the chicks' arrival. An 18-inch high, cardboard or wire mesh guard ring around the brooder will help keep the chicks near the heat, feed, and water. The guard ring should be large enough to allow 3 feet of space between the ring and the outer edge of the brooder. Remove the ring after four to seven days.

Brooding the Chicks

The starting temperature under the brooder should be 90 °F. at 2 1/2 inches above the floor. Reduce this temperature 5 degrees each week until you reach a 70° temperature. You should maintain a 70° brooder temperature until the broilers are marketed or, in the case of pullets, until they reach eight weeks of age. Beyond eight weeks, keep the brooder temperature between 60 and 65 degrees until the pullets reach maturity.

If the chicks are evenly distributed over the floor and are eating and drinking well, the temperature is adequate. If the chicks are huddled together beneath the brooder, the temperature is too low and you should increase it. When the chicks are gathered near the brooder guard and panting, they are too hot and you should reduce the brooder temperature. Don't let the chicks become either chilled or over-heated. Close the brooder house on cool nights and allow plenty of ventilation on warm days.

Place feed and water around the brooder before placing the chicks on the litter. During the first three weeks, 50 chicks will require two baby chick troughs (2 feet long) and three half-gallon water fountains. For the first three days, you can place additional feed on egg flats to teach the chicks to eat sooner. You can fill feed troughs full the first day or two, but fill them not more than one-half to two-thirds full thereafter to reduce feed wastage. You can place the water fountain on a short piece of board (1"x 6"x 6"0), which will keep the water clean.

Management of Broiler Chicks

You can feed a good commercial chick starter ration containing 23 per cent protein for the first five to six weeks. Follow this with a finisher feed with 20 per cent protein until the broilers reach the desired slaughter weight. A recommended feeding schedule and the nutrient levels of the ration are shown. The chicks should have access to the feed and water at all times

You should clean the water fountains daily and the feeders frequently. Refill the waterers as needed to provide an adequate supply of cool, clean drinking water. When the broilers are three weeks of age, provide the equivalent of five one-gallon waterers or an 8-foot automatic waterer. Also provide two medium-sized feed troughs (4 feet long).

Establish a strict sanitation program and follow it for disease prevention. Damp litter tends to increase the incidence of disease. Remove all wet or caked litter as soon as possible and ventilate the house to remove the remaining damp air. Occasional stirring of the litter will help keep it dry.

Feeding pullets

Managing replacement pullets is much the same as rearing broilers. The major differences are in the feeding and vaccination programs and in establishing a good lighting program. Proper management is of major importance in rearing a laying flock that will produce many high quality eggs throughout the year.

Meat-type chicks started as replacement pullets should be fed less concentrated diets than broilers so the body weights and sexual maturity are restricted. Many problems in laying flocks can be related to feeding broiler-type diets to young pullets. Following a feeding schedule such as shown will help prevent overweight hens that overeat and have poor egg production records.

You should feed pullet chicks a 20 percent protein starter ration for the first six weeks, followed by a 16 percent grower ration until the pullets are 14 weeks old. Between 14 and 22 weeks of age, egg-type pullets should be fed a developer ration containing about 12 percent protein. You may feed the developer ration until 24 weeks of age for meat-type pullets. Then feed the pullets a 16 percent protein laying ration.

You should consider a good disease prevention program when rearing pullets. One-day-old chikcs should be vaccinated at the hatchery for Newcastle, infectious bronchitis and Marek's diseases. The birds should be revaccinated at four to five weeks and 16 weeks of age for Newcastle disease, using the B1 type vaccine in the drinking water. The same method should be used at 16 weeks for infectious bronchitis.

Young pullets are usually vaccinated for fowl pox at 12 weeks of age using the wing-web method. In areas where fowl pox has previously been a problem or where mosquitoes are frequently found near poultry flocks, the pullets may have to be vaccinated for fowl pox as early as one day of age. To prevent outbreaks of coccidiosis, pullets should be provided a ration containing an effective coccidiostat until they reach 14-20 weeks of age. A summary of a good disease prevention program is shown. You should use this program as well as sound sanitation practices. Both are equally important in preventing disease.

The third important factor in raising pullets is good lighting. Not following a well designed program for only a few days may cause serious harm to the flock's development.

All lighting programs used with commercial flocks use the principles of decreasing light stimulation for growing pullets and increasing light stimulation after the mature pullets have reached production. Light is a very strong stimulating factor in poultry and must be carefully managed. Thumb rule: Never subject pullets to increasing light and never subject layers to decreasing light.

Until the pullets are three weeks old, you should give them 20 to 24 hours of light daily. Put the birds on a decreasing day-length lighting program when they are between 3 and 22 weeks of age. Determine the date when the pullets will be 22 weeks of age and find the nearest corresponding date in the table provided. Next to this date is the length of day that you should provide to the pullet at three weeks of age. Shorten this lighting duration by 15 minutes each week until at 22 weeks the birds are receiving a natural day length for that time of year. You may turn on the lights before sunrise, turn them off after sunset, or both, but the length of light received each day should correspond to the lighting schedule. You can put the pullets on a lighting program designed for laying hens at 22 weeks of age.

Poultry respond primarily to the length of the daily lighting period rather than the light's intensity. A 40-watt incandescent light bulb will supply enough light for a 10' x 15' pullet or layer house that can house 50 broiler-type pullets or 75 egg-type pullets. If you use a reflectorized light fixture, you may substitute a 25-watt bulb.

You should follow all management practices used in rearing broilers when raising pullets except for those changes already discussed. Always consider the birds' comfort for best results. Always provide comfortable house temperatures and adequate floor space. After the birds are 8 weeks old, allow 2 1/2 to 3 square feet of floor space for each pullet.

Layer Management

You can achieve the housing and management of layer hens using one of two methods, caged layer production or floor production. Either method can keep the hens in production throughout the year if you meet proper environmental and nutritional needs.

You should locate the poultry house away from other farm structures. The ground should allow good water drainage. Adequate light fixtures are needed to provide at least 1/2 foot-candle of light intensity. Adequate light is present if you can see the water and feed levels in the troughs after allowing enough time for your eyes to adjust to the dim lighting. Fresh, clean water should be available.

The house should have plenty of open wall space to allow for ventilation and sunlight. Wall openings from top to bottom give good summer ventilation. Place one-inch poultry wire netting over all openings to separate the hens from other birds and animals, both wild and domestic. Removable curtains or doors are recommended so you can open or close the openings as the weather changes. Keep the house dry and comfortable by ventilating from all sides in the summer and closing most openings in winter.

The caged layer production method consists of placing the hens in wire cages, with feed and water being provided to each cage. The birds are housed at a capacity of two to three hens in each cage, which measure approximately 12'x16"x18". The cages are arranged in rows that are placed on leg supports or suspended from the ceiling so the floors of the cages are about 2 1/2 to 3 feet above the ground. Water is supplied by individual cup waterers or a long trough outside the cages that extends the length of the row of cages. The feed trough is also located outside the cages and runs parallel to the water trough on the opposite side of each cage. The cages are designed so the eggs will roll out of the cage to a holding area by means of a slanted wire floor. This method of housing is used primarily with egg-type layers kept for infertile egg production.

The floor production method is designed for either egg-type or broiler-type birds kept for fertile or infertile eggs. In commercial flocks this method is used when fertile eggs for hatching are needed. The birds are maintained in the house on a litter covered floor, giving the term "floor production."

Provide horizontal roost poles 2 to 3 feet above the floor. Allow 9 inches of roost pole for each hen, with poles 15 inches apart. One nest 14 inches wide, 12 inches high, and 16 inches deep is needed for each five hens. A mash hopper 5 feet long and open on both sides is adequate for 25 hens. Three 3-gallon pans provide adequate watering space for 30 hens. Clean, scrub, and disinfect the house and equipment thoroughly before placing the pullets in the laying house after it has dried. Put 3 inches of litter material in the nests and 4 to 6 inches of litter on the floor.

Regardless of which production method you use, you should give the 22-week-old pullets an increasing daily light schedule after placing them in the laying house. If you raised the pullets on the lighting program outlined in this publication, you should increase the length of daily light 15 minutes each week after the birds enter the laying house. The increased light will stimulate egg production and help maintain production throughout the year. The day length increases should continue until the birds are receiving 16 to 18 hours of light each day. The day length should remain the same for the rest of the laying period. After the birds begin to produce eggs, do not reduce the total duration of light, including both natural and artificial.

You should feed the birds a nutritionally balanced commercial laying mash containing 16 per cent protein. Use a special breeder ration if you are saving the eggs for hatching purposes. The breeder diets contain higher levels of vitamins that help produce higher hatchability and healthier chicks. Poultry older than 16 to 18 weeks do not require a ration containing a coccidiostat unless a coccidiosis outbreak occurs. If you provide a commercially produced layer ration, you do not need additional oyster shell, grit, or grain.

Culling is the removing of non-productive or uneconomical hens from the flock. The first time to cull pullets is in the selection for the laying house. Remove all pullets that are permanently disabled or diseased. Do not, though, be too critical of the birds at this stage, since some will mature at a later age.

After the flock reaches a good production level, culling will eliminate costly feeding of unproductive birds and provide more space for the productive birds.

A problem often encountered in laying hens is prolapse of the oviduct. It is more frequent in the heavier and earlier maturing hens. The oviduct inverts and protrudes outward from the vent area. The inversion of the oviduct is usually permanent and results in other birds' pecking this area until the affected bird bleeds to death.

Prolapse of the oviduct can be caused as a result of genetic traits, early maturation, or a combination of genetics and poor management. Pullets that are overfed and over stimulated with light often begin egg production before their reproductive systems have had time to develop completely. An early problem sign is a high incidence of blood streaked egg shells. If prolapse and pickouts become a problem, you can round or blunt the beaks of the aggressive hens by using a hot cauterizing blade. You should remove the affected birds from the flock and not return them. These birds will be prone to prolapse, and their return to the flock may incite more widespread pickouts by aggressive hens.

Broodiness is often a problem in floor production housing. It is characterized by a hen's wanting to build a permanent nest and begin "setting." You can solve the problem by removing the hen from the flock and placing her in a wire-floored cage for three to four days. You should supply ample feed and water to the affected hen. Then you can usually return the hen to the flock with no further problem. Repreat the treatment if the hen continues to be broody.

Near the end of the first year of lay, egg production may become so poor that the poultry man is faced with a decision of molting his birds or selling them. Molting refers to the life period when hens stop producing eggs, lose their feathers, and begin to grow new ones. It is believed that molting allows the female to rest and restore her body and reproductive system.

When economical, the poultry man may use one of a number of techniques to start the molting process. The "forced molt" will improve production above pre-molt levels, improve the feed efficiency, and improve egg shell and albumen quality.

The disadvantages are that production levels will fall more rapidly than before the molt. Also, a larger percentage of defective eggs will result with a non-productive period during the molt and a higher mortality during the molt. You should carefully evaluate the economic factors before starting a "forced molt."

Many methods have been used to initiate molt, but the most common is one that restricts the light and feed supply to the bird. To force a molt, remove all feed and artificial light for seven days or until all the birds are out of production, whichever is later. Then feed the birds 10 pounds of feed for each 10 hens and gradually increase the amount of feed until the birds are on full feed by the 45th day. Resume the lighting program on the 35th day with 14 hours of light daily and a gradual increase to the previous lighting level by the 49th day.

Often people are concerned about a problem in laying flocks referred to as "bare back." Bare back is usually observed in older, floor layer or breeder flocks. As the birds age, the feathers become more tattered and broken, especially in high producing flocks. The continuation of egg production distinguishes this condition from molting birds. Normally the best laying birds in the flock will have the largest amount of "bare back" condition. This particular feathering condition is not a sign of disease of ill health and will correct itself after the birds undergo a natural or forced molt. This condition will not affect performance unless it occurs during the winter when affected birds may be more vulnerable to the cold.

Roosters

Do not keep roosters in the flock unless you have a specific need for fertile hatching eggs. Roosters do not contribute to egg production and occupy space and consume feed that can be more efficiently used for additional laying hens. Roosters are not required in a flock to maintain the production of eggs for consumption. If fertile eggs are desired, provide one rooster for every 10 to 12 hens.

Disease and Parasite Control

Coccidiosis is the most common disease found in young, unmedicated flocks. This protozoan disease, characterized by diarrhea, unthriftiness, and some mortality, is transmitted by the hens' eating coccidia oocysts from contaminated droppings. You can prevent the disease by feeding rations containing a coccidiostat. A good coccidiostat prevents outbreaks of coccidiosis while allowing the birds to develop a natural immunity.

Laying hens will not require a feed that contains a coccidiostat. However, layers, especially young layers on littered floors, may experience coccidiosis outbreaks. If coccidiosis is diagnosed, treatment is normally given through the drinking water. In case of an outbreak, start treatment measures immediately.

Several other diseases may be seen, such as aspergillosis, infectious bronchitis, Newcastle, Mareks disease, fowl pox, epidemic tremor, Gumboro, necrotic enteritis, fatty liver syndrome, and blackhead. Many diseases can be prevented by using a vaccination program such as the one shown.

Watch for external and internal parasites such as intestinal roundworms, cecal worms, mites, ticks, and lice. Piperazine compounds are effective in controlling intestinal roundworms. Phenothiazine is used to treat cecal worms. Capillary worms are controlled by using Hygromycin or meldane, and tapeworms should be treated with butynorate. These are the four major internal parasites in poultry. Practice a rigid sanitation program.

Care of Eggs

A freshly laid egg loses quality rapidly if it is not handled properly. Plenty of clean litter in the nests reduces the number of dirty or cracked eggs.

You should gather the eggs daily in mild weather and at least two times daily in hot or cold weather. Place the eggs in a cooler immediately after gathering them and store them at 50 to 55 °F. Do not store eggs with foods or products that give off pungent odors, since eggs may absorb the odors. Do not wash eggs saved for hatching purposes. Save only clean and slightly soiled eggs for hatching. Do not incubate dirty eggs. Store eggs in a cool place with the large ends up. It is not advisable to store the eggs longer than one week before setting them in an incubator.

Source: Mississippi State University Extension Service - January 2006