Breeder Nutrition and Chick Quality

By Marcus Kenny and Carolyne Kemp, Aviagen - This article by Aviagen discusses how the nutrition of the breeder hen affects the chicks physiology at hatching.

The developing embryo and the

hatched chick are completely

dependent for their growth and

development on nutrients deposited in

the egg. Consequently the physiological

status of the chick at hatching is greatly

influenced by the nutrition of the breeder

hen which will influence chick size,

vigour and the immune status of the

chick.

| Table 1. The necessary change in hatchery or broiler performance to equalise profitability when breeder feed cost is changed by 1% per tonne (for example from £UK 140.00/tonne to £UK141.40/tonne or £UK138.60/tonne). | |||

| Hatch of total eggs (%) | 0.24 | ||

| 42 day liveweight (g) | 7.4 | ||

| 42 day FCR | 0.0015 | ||

| 42 day mortality (%) | 0.07-0.45* | ||

| *depending on age of mortality. Calculated using input-output values for UK industry 2003 (Kemp and Kenny 2003). | |||

The financial effects

Nutritional decisions for breeders need

to take account of the overall economics

of the whole production cycle.

Table 1 shows the changes in hatchery

and broiler performance that are required

to equalise the effect of a 1%

increase in breeder feed cost on the profitability

of the whole production cycle.

Only one of these changes is required

to have the necessary economic effect;

in practice all are likely to move positively

making the measurements of any

one change difficult.

The calculations are done under typical

UK 2003 conditions and they show quite

clearly that small improvements in bird

performance are required to ‘pay’ for

more expensive breeder feed.

Conversely, apparent savings in

breeder feed cost can readily lead to an

overall loss if small changes in broiler

performances are ignored.

Similar economic analyses have been

conducted by Mississippi State University

which, based on US integration

2002 costs, demonstrates that a measurable

improvement in progeny liveability

as a result of hen diet change can be

profitable.

The key point is that trying to cut the

cost of a breeder feed may easily reduce

the profitability of the overall enterprise.

Influence of feed allocation

Underfeeding the hen can have an

impact on chick quality and this is particularly

noticeable in the early production

period. Modern hybrid parent flocks

commence production at a faster rate

than in the past and consequently egg

output increases over a shorter time span

during the early laying period. Feed allocations

during this period have not necessarily

increased in line with this egg

production trend. Low feed allocation

intake by young commercial breeder

flocks has been shown to compromise

nutrient transfer to the egg, resulting in

increased late embryonic death, poorer

chick viability and uniformity.

In a recent study by Leeson (2004)

broiler breeders were fed different levels

of feed through peak production varying

from 140 to 175 grams. Although the

increased feed allocation increased

bodyweight there was no influence on

egg size, however chick weight was

influenced by feed allocation (Table 2).

Of equal importance is the effect of

overfeeding on ovarian development. In

experimental studies ad libitum feeding

has been the most widely used model for

overfeeding which can result in excessive

follicular development or Erratic

Oviposition and Defective Egg Syndrome

(EODES).

Flocks with EODES generally have

poor shell quality, a reduced duration of

fertility and poor hatchability. It is also

known that fewer sperm will survive but

it is not clear how the surviving sperm

are affected and if they generate a

weaker embryo. The same authors also

warn that the effect of aggressive feeding

two to four weeks after photostimulation

reduces productive performance

throughout the life of the flock.

In this period the bird switches from

primarily growth to a reproductive state.

The young birds’ reproductive hormone

system is not mature enough to deal with

high nutrient intakes; nutrients are

instead metabolised to egg yolk lipid

which contributes to excess follicle

development.

Research shows that nutrient supply to

the broiler breeder is of consequence to

chick quality and production performance.

This places greater emphasis on

the nutritionist providing the correct

nutrient density diet and the flock manager

to provide appropriate feed intake

to the bird coming into lay.

| Table 2. The effects of breeder feed levels on chick weight. | |

| Peak breeder feed (g/b/d) | 30 week breeder chick weight (g) |

| 140 | 40.3 |

| 147 | 40.0 |

| 155 | 41.5 |

| 162 | 41.7 |

| 169 | 41.8 |

| 175 | 42.0 |

Diluted breeder diets

The use of diluted breeder diets is receiving a lot of attention in Western Europe on the basis of improvements in bird welfare. Experimental work feeding low energy density diets to young parent stock gave a delayed onset of oviduct development, increased early egg size, faster development of the embryo and a higher live weight of day old chicks. When broiler mortality was above average, low density broiler breeder feeds gave a significant reduction in mortality of offspring. Other experimental work showed improvements in breeder productive performance when diluted diets were fed in the rearing period.

Vitamins

Vitamins are involved in most metabolic

processes and are an integral part of

foetal development, therefore the consequence

of suboptimal levels of these

nutrients in commercial diets are known

to result in negative responses to both

parent and offspring performance.

Vitamins account for about 4% of the

cost of a breeder feed, so economising

on vitamin inclusion rates is rarely an option

| Table 3. Some practical recommendations for vitamin supplementation of breeder feeds (Fisher and Kemp 2001). |

|||

| Vitamin | Leeson & Summers (1997) | DSM | Ross |

| A (iu/g) | 7 | 10-14 | 13 |

| D3 (iu/g) | 3 | 2.5-3.0 | 3 |

| E (mg/kg) | 25 | 40-80 | 100 |

| K (mg/kg) | 3 | 2-4 | 5 |

| Thiamine (mg/kg) | 2.2 | 2-3 | 3 |

| Riboflavin (mg/kg) | 10 | 8-12 | 12 |

| Pyridoxine (mg/kg) | 2.5 | 4-6 | 6 |

| B12 (mg/kg) | 0.013 | 0.02-0.04 | 0.03 |

| Nicotinic acid (mg/kg) | 40 | 30-60 | 50 |

| D-pantothenic acid (mg/kg) | 14 | 12-15 | 12 |

| Biotin (mg/kg) | 0.2 | 0.2-0.4 | 0.3 |

| Folic acid (mg/kg) | 1 | 1.5-2.5 | 2 |

The levels of vitamin supplementation

recommended by different sources have

been summarised in Table 3. Generally

there is a shortage of information on vitamin

requirements of broiler breeders

especially when related to offspring performance.

Most of the breeder work is

quite dated and since that time breeder

performance has changed.

It would be impossible to review all the

literature in this article, however a

review of work on fat soluble vitamins,

biotin and pantothenic acid have shown

that vitamin E has the largest impact on

progeny.

| Table 4. Impact of dietary breeder vitamin status on bodyweight, enzyme activities, tissue characteristics and immunity of progeny. | ||

| Vitamin | Progeny response | |

| Vitamin A | Increased liver vitamin A in embryonic and chick liver but decreased vitamin E, carotenoids and ascorbic acid. Surai et al. (1998). | |

| Carotenoids | No positive impact on chick growth, organ development or humoral immunity in chicks five weeks post hatching. Haq et al. (1995). | |

| Carotenoids | Transferred from the hen to the yolk but not absorbed well by the embryo and subsequent chick. Haq and Bailey (1996). | |

| Carotenoids and Vitamin E | Carotene, vitamin E, and their combination improved and vitamin E lymphocyte proliferation, but only vitamin E improved humoral immunity. Haq et al. (1996). | |

| Vitamin E | Vitamin E levels of 150 and 450mg/kg increased passively transferred antibody levels in chicks to Brucella abortus up to seven days of age. Jackson et al. (1978). | |

| Vitamin E | Increased vitamin E in chicks’ yolk sac membrane, liver, brain and lung all of which had reduced susceptibility to peroxidation. Surai et al. (1999). | |

| Vitamin E | Increased progeny antibody titers to sheep red blood cells at hatch. Boa-Amponsem et al. (2001). | |

| Vitamin E and Selenium | Increased liver glutathione activity in chicks. Increasing selenium increased selenium dependant glutathione peroxidase in chick liver. Surai (2000). | |

| Vitamin D | Tibial calcium was increased at two weeks post hatching and tibial ash increased at four weeks of age by increased vitamin D3. Ameenudin et al. (1986). | |

| Vitamin K | Chicks from hens fed vitamin K deficient diet had reduced tibial glutamic acid levels at day one and 28 post hatching but tibial glutamic acid was restored by supplementing the chick diet with vitamin K. Lavelle et al. (1994). | |

| Biotin | Foot pad dermatitis and incidence of breast blisters were decreased in some trials in chicks from hens fed biotin fortified diet. Harms et al. (1976). | |

| Biotin | As biotin increased in the hens’ diet, yolk and chick plasma also increased. Biotin concentration in chick plasma was poorest from young hens. Whitehead (1984). | |

| Pantothenic acid | Liveability of chicks was best when hens were fed 20mg/kg diet of pantothenic acid. Utno and Klieste (1971). | |

| Adapted from M. Kidd 2002 | ||

The production and economic effects

of vitamin E supplementation are best

shown by Hossain et al (1998) where a

basal corn soya feed was supplemented

with 25, 50, 75 and 100mg/kg vitamin E.

The effects on hatchability were not

significant; however the best hatchability

was obtained at 50mg/kg at 52 weeks.

Offspring immune response continued

to increase up to 100mg/kg. In the same

studies higher final bodyweights at 42

days, improved FCR and reduced mortality

were observed in chicks from eggs

which had been injected with vitamin E

in ovo.

Haq et al., (1996) working with very

high levels of vitamin E (134mg/kg versus

412mg/kg) found no growth response

to 21 days and an improvement in FCR

for the offspring of hens receiving the

supplemental feed.

In other studies the combination of

selenium and vitamin E to broiler breeders

has been shown to increase liver glutathione

activity of progeny.

In general it seems to be justified to

supplement practical breeder feeds with

100mg/kg vitamin E.

There appear to be mixed reports on

the efficacy of vitamin C; some experiments

suggest a positive response, but a

more recent study failed to detect any

benefit on any production parameter.

This lengthy study used corn soya diets

supplemented with 75mg/kg stabilised

vitamin C which when analysed recovered

49mg/kg which might explain the

variability of response.

The influence of increased vitamin levels

fed to young parent stock on progeny

performance is an area which has

received significant commercial interest.

Work conducted at Aviagen Ltd has

shown chicks derived from 31 week old

parent stock fed elevated levels of vitamins

showed improved growth to 11

days and reduced mortality compared to

chicks derived from 42 and 45 week old

parents.

Similar responses have been found in

the field where chicks derived from

young parents fed increased levels of vitamins have benefited in terms of viability

and liveability. Perhaps this supports the

need for further work exploring the vitamin

requirements of the breeder in the

early production period.

Whitehead (1991) proposes that a basis

for making recommendations is to feed

vitamin levels that maximise the resulting

level in the egg.

For vitamins with active transport

mechanisms (thiamine, riboflavin, biotin,

cobalamin, retinol and cholecalciferol)

these levels reflect the saturation of binding

proteins.

Levels derived in this way include

10mg/kg for riboflavin and 250 microgram/

kg for biotin. Whitehead (1991)

contrasts this level of riboflavin with the

conventional requirement (4mg/kg in this

case) but the higher figure – the upper

limit to nutritionally useful range – may

be a better guide to good commercial

practice.

| Table 5. Blood cell count of the broiler derived from parents fed high or low vitamin and mineral levels (Rebel et al 2004). | |||

| Breeder low vitamins/minerals | Breeder high vitamins/minerals | ||

| Heterophil | 5.3 | 3.8 | |

| Lymphocyte | 4.6a | 21.4b | |

| Monocyte | 1.1 | 5.3 | |

| Basophil | 0.0a | 5.4b | |

| Table 6. Summary of minerals fed to breeders shown to have an effect on progeny performance. | ||||

| Growth | Liveability | Immune function | Skeletal | |

| Fluoride | X | |||

| Phosphorus | X | |||

| Selenium | X | |||

| Selenomethionine | X | X | ||

| Zinc | X | X | X | |

| Zinc and methionine | X | |||

| Adapted from M. Kidd 2002 | ||||

Vitamins and chick immunity

Reference has already been made to the

effect of vitamin E on chick health and

immune function, while other vitamins

have been researched none show the

same degree of effect as vitamin E.

Table 4 summarises work investigating

the effect of different vitamins fed to

breeders and consequent impact on

progeny health.

Recent work by Rebel et al (2004)

investigated the effects of several elevated

levels of vitamins and trace elements

fed to breeders and broilers on the

immune system of birds infected with

malabsorption syndrome.

Broilers derived from breeders fed elevated

vitamins and mineral levels had

increased numbers of leukocytes at day

old which indicated stimulation of the

immune system (see Table 5).

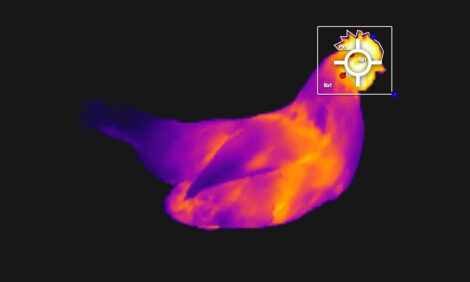

Fig. 1. The effect of protein-to-energy ratio in the breeder feed on chick weight at hatch (Spratt and Leeson 1987).  |

Major minerals

Calcium, phosphorus, sodium, potassium, magnesium and chloride are involved in shell formation hence general improvements in shell quality lead to better egg and chick quality. Variations in maternal phosphorus supply have been shown to influence bone ash of young but not older progeny. Broiler performance was not affected by these treatments so the practical significance of this work is not clear but the use of relatively low phosphorus levels in breeder diets, while benefiting egg shell quality, may not lead to the best possible bone integrity in the early stages of growth.

Trace minerals

Most interest in this field has centred on

the use of chelated minerals which have

been shown to increase deposition in the

egg and transfer to the tissues of the hen

and the embryo.

Most recent work has focused on the

antioxidant status of breeders, embryos,

offspring and the role of selenium.

Surai (2000) has shown the role of

Selenomethionine on both vitamin E and

glutathione peroxidase levels in eggs,

embryos and chicks up to 10 days of

age.

The economic benefits of using

Selenomethionine compared with

sodium selenite have been examined in

a number of unpublished field trials in

the UK. Hatchability improvements

ranged between 0.5-2.0 chicks per 100

eggs and in another trial 0.3-0.7 chicks

per 100 fertile eggs. Few of these tests

involve a proper assessment of subsequent

broiler performance although

comments about chick quality are generally

positive.

In one of the commercial trials mentioned

an improvement of 0.5% in mortality

and cull rate at 10 days was

observed when organic selenium

replaced sodium selenite.

Research has indicated that the

improvements in chick immunity as a

result of mineral fortification of hen diets

may result in improved liveability.

Flinchum et al. (1989) demonstrated

that leghorn breeders fed supplemental

zinc methionine to a zinc adequate diet

had progeny with improved survival to

an E. coli challenge. Similar improvements

to progeny liveability were seen

with breeders fed supplemental zinc and

manganese amino acid complexes.

Table 6 is a summary of those minerals

which, when fed to breeders, have an

effect on progeny performance.

Nutrient levels in the breeder diet

There is clear evidence that a high protein

to energy ratio depresses hatchability,

and probably chick performance.

The experiment by Whitehead et al.

(1985) shows the effect of excess protein

where the higher protein level reduced

reproductive performance, producing

3.1 fewer chicks per 100 fertile eggs.

Chick quality was also reduced so that

the difference in saleable chicks was 4.0

per 100 fertile eggs.

The effect of energy protein ratio in the

breeder feed is shown in Fig. 1. This

emphasises both the effects of excess

and inadequate protein, and also indicates

that the optimum level is quite

steeply defined.

According to this trial the optimum

protein level is at 5.52g protein per

100kcal which converts to an optimum

of 15.18% protein for a diet containing

2,750cal/kg of feed.

The protein level of the diet and its

ratio to energy is important not only for

parent performance but also for chick

quality.

| Table 7. Commercial comparison of breeder feeds based on wheat or maize (400g/kg). | ||

| Advantage of maize over wheat based feed | ||

| Mortality during lay (%) | -1.7 | |

| Total eggs (per hen housed) | +3.8 | |

| Hatching eggs (per hen housed) | +4.8 | |

| Hatching/total eggs (%) | +0.9 | |

| Hatch of set eggs (%) | +0.6 | |

| Hatch of fertile eggs (%) | +1.1 | |

| Second quality chicks | -0.1 | |

| Based on a comparison of two commercial houses each containing 6500 female grandparent breeders. Data to 58 weeks (Ross Breeders, unpublished data, 1998). | ||

The effect of feed ingredients

There is evidence of improved breeder

performance when maize is compared to

wheat as the main cereal in breeder

feeds. From a survey of many depleted

commercial flocks overall hatch of fertile

eggs in the UK based on wheat diets and

Brazil based on maize diets is 83.3 and

86.2 per 100 eggs respectively.

Other management factors may contribute

to this difference in hatchability

other than cereal source; male management

is very good in Brazil and the

resulting high fertility may also contribute

something to this difference.

Unpublished commercial development

trials from the Netherlands and Aviagen

Ltd grandparent flocks (see Table 7) support

this observation.

The most likely benefit of maize is

probably in shell quality and thickness.

From the same data average poorer

shells with specific gravity of <1.08

accounted for 26.1% of eggs from wheat

fed hens and 17.1% from maize fed.

Studies of hatching losses showed less

late dead embryos (>18 days) and less

bacterial contamination. These two

responses are expected with eggs of better

shell quality.

Evidence about fat levels and sources is

conflicting but there is no question that

this is an important consideration. Added

fat levels should be kept low in breeder

feed (1-3%) and preference given to

unsaturated vegetable oils rather than

saturated animal fats. Work from

Mississippi State University compared

maize oil and poultry fat and generally

supported the use of more unsaturated

fat (see Table 8).

Maize oil increased 21 day bodyweight

over that of poultry fat and improved

slaughter weight of broilers in comparison

to equal levels of poultry fat and

lard.

| Table 8. Experiments comparing fat sources and/or levels for broiler breeders. | ||

| Reference | Fats compared | |

| Brake (1990) | PF | |

| Brake et al. (1989) | PF | |

| Denbow & Hulet (1995) | SBO, PF, FO | |

| Peebles et al. (1999a, b) | CO, PF, LA | |

| Peebles et al. (2000a) | PF, CO, LA | |

| Peebles et al. (2000b) | PF, CO, LA | |

| Fats: PF – poultry fat; SBO – soybean oil; FO – fish oil; CO – corn oil; LA – lard | ||

Summary

Over and undersupply of nutrients into

and through lay can have a very significant

impact on breeder production and

quality of progeny. This places greater

emphasis on the nutritionist providing

the correct nutrient density diet and the

flock manager to provide appropriate

feed allocation in lay.

Addition of micronutrients to the

breeder has been shown to be beneficial

to progeny quality especially in the early

production period. Use of specific

dietary ingredients such as maize can

affect breeder performance and progeny

quality. Both on economic grounds and

on biological grounds, high quality nutrition

of breeders is well justified.

Source: Aviagen - June 2005