Controlling Body Weight of Turkey Breeder Hens Without Feed Restriction

A researcher at Iowa State University was able to control turkey hen bodyweight by ad-libitum feeding of a diet of lower nutrient content during the rearing period, without using physical feed restriction. The lighter hens produced more eggs while the heavier birds produced larger eggs.The commercial breeding sector of the turkey industry has been very successful at continually improving the commercial traits, i.e. bodyweight, breast muscle yield, that are the economic drivers of the industry, according to Dr Michael Lilburn, Ohio State University.

It has been recognised for many years that the continual selection for traits of economic importance may have negative correlated effects on reproductive efficiency. The turkey industry has partially countered this via the use of artificial insemination to maintain high levels of fertility, but there is no simple, identified management tool for optimising production efficiency in commercial breeder hens.

It is accepted that bodyweight control of turkey hens during rearing is essential for optimising egg production but physical restriction of hens as practised in broiler breeders is not an accepted option. Thus, there is a need for studies whose objective is to control body weight in replacement hens via ad libitum, controlled feeding of low nutrient dense diets.

The primary objective of this research, sponsored by the US Poultry and Egg Association, was to create different bodyweight groups during rearing via dietary manipulation. This was followed by individual weighing of hens at 24 weeks and allocating them into replicate pens of Heavy, Medium and Light body weight hens. These body weight treatments were designed to bracket the target bodyweights recommended by the primary breeder, Hybrid.

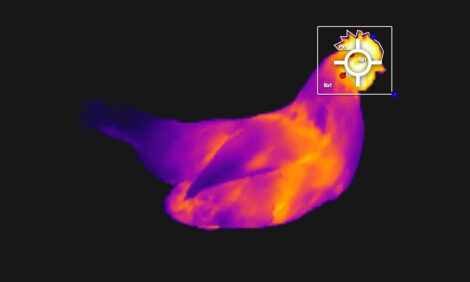

In addition to hen-day egg production and egg weight determinations, a sample of hens from each treatment were euthanised for carcass, reproductive organ and selected skeletal measurements at one week (30 weeks) and three weeks post-photostimulation (32 weeks).

The dietary rearing treatments resulted in hens that weighed 24.45 and 23.0 lbs at 24 weeks, 26.6 and 25.6 lbs at 30 weeks and 24.8 and 24.1 lbs at 42 weeks. The Heavy, Medium, and Light hens weighed 27.6, 26.3 and 24.3 lbs at 30 weeks and 25.6, 24.6 and 23.0 lbs at 42 weeks, respectively.

After the onset of hen-day egg production, the Light treatment hens had significantly better hen-day egg production than either the Medium or Heavy hens. The Heavy hens had approximately a two-gram improvement in egg weight at four, eight and 10 weeks of egg production compared with the Light hens. The Medium weight hens were intermediate.

At 30 weeks of age, hens in the Heavy, Medium and Light body weight groups had corresponding differences in carcass weight but there were no significant effects on shank length, follicle number or reproductive tract weight.

At 32 weeks, there were also no bodyweight treatment effects on follicle number or reproductive tract weight but there was a progressive decrease in femur, tibia and shank length in the sampled hens as body weight declined.

Total carcass lipid (as a percentage of dry matter) increased from 42 per cent to 51 per cent between 30 and 32 weeks of age, but there were no significant differences between body weight groups. The greatest increase in carcass lipid occurred in the Light body weight group (41.7 per cent to 53.5 per cent), and this resulted in a marginal age by body weight interaction (P<0.087). Across all three body weight groups, there was a significant decline in bodyweight between 30 and 42 weeks of age.

The lower plane of nutrient intake during rearing significantly reduced body weight at 24 and 30 weeks, concluded Dr Lilburn. Carcass lipid increased between 30 and 32 weeks, particularly in the Light hens. He added that, at 32 weeks, there was a decline in femur, tibia and shank length with each decrease in bodyweight among the Heavy, Medium, Light groups, and this may have reduced maintenance energy needs and allowed for increased carcass lipid deposition.

June 2014