Government Interference in Poultry Disease Eradication: Avian Flu in Mexico

Low-pathogenic avian flu in Mexico represents a direct cost to the local poultry industry of US$246 million annually over the last 18 years, or a cumulative $4.4 billion, according to Armando Mirandé, DVM, MPVM, MAM, ACPV. He outlines how these costs have mounted up and suggests six steps to setting the country's poultry industry back on the path to good health again.Impacts of Avian Flu on Mexico's Poultry Meat and Egg Sectors

Despite occupying the fifth place in both, chicken meat and egg production in the world, Mexico has imported a record number of tons of table eggs and chicken meat in 2013, almost exclusively from the United States, writes Dr Armando Mirandé in a paper he presented at the National Meeting on Poultry Health, Processing, and Live Production in Ocean City, Maryland, US in October 2013. Even with all these imports, prices soared during the first half of 2013 by an average of 15 per cent for eggs and 32 per cent for meat.

This increase may not sound like much but they are in addition to price increases of 40 per cent and 10 per cent for eggs and meat, respectively, in 2012. Egg prices still reflect the loss of 20 per cent of the national flock in 2012 due to the highly pathogenic H7N3 AI outbreak in the state of Jalisco.

Meat prices increased in 2013 due to subsequent outbreaks of the same virus in the states of Aguascalientes and Guanajuato in early 2013, causing an additional loss of approximately 13 per cent of all broiler parent stock in the country and which is already insufficient to supply its demand.

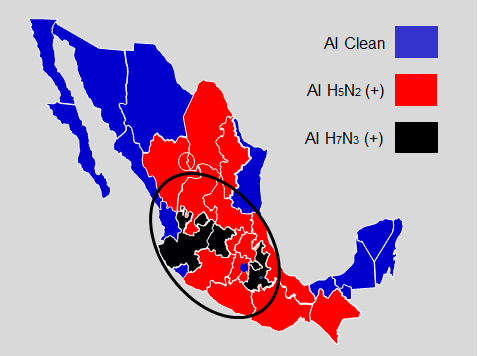

Additional outbreaks of this same virus were reported also during the first half of 2013 in the states of Tlaxcala and Puebla and it is believed there are other states where outbreaks have not been reported (Figure 1).

To compensate for this interruption in supply, 2013 saw record imports of broiler hatching eggs from the US as well. Due to discontent in the general population for inflation of poultry products and after public remarks from the Secretary of Economy referring to poultry producers as “greedy”, government, in an unprecedented action, allowed the importation of broiler meat from Brazil despite the absence of a free trade agreement between the two countries. To date, three processing plants have been certified to export meat to Mexico and, ironically, all three Brazilian plants belong to companies with broiler production in Mexico through wholly-owned subsidiaries.

One would tend to believe an outbreak of such magnitude could harm an entire industry, according to Dr Mirandé. Yet due to major economic laws of supply and demand the last 15 months have been the most profitable for both, egg and broiler meat producers in Mexico in a very long time.

This fact even prompted a member of an opposing political party in the House of Representatives to accuse the largest broiler integrator of deliberately disseminating the virus in order to restrict supply and force price escalation.

As an example of this lucrative year, its Mexican operation represents 10 per cent of Pilgrim's Pride's volume but 30 per cent of its profit, according to Stephens, Inc.'s analyst, Farha Aslam. This is in a year when Pilgrim’s showed record profits in the US. How noble the Mexican market is? Profits have already begun to shrink as over-production from imported hatching eggs and the unexpected Brazilian imports finally caught up with the market.

So, was this outbreak good for the poultry industries in the US and Mexico?

Adding up the Costs of Avian Flu to the Industry

Last summer, Mexico witnessed what is considered one of the world’s costliest poultry outbreaks ever recorded when highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H7N3 was confirmed in commercial table egg layers in the western central state of Jalisco, reports Dr Mirandé.

Government and industry worked together to activate and implement a series of pre-established control measures. Both monetary and human assets were made available to enforce strict vigilance to contain, and eventually eradicate, such an epizootic. Unfortunately, they simply failed.

At the end of the day, corruption at multiple levels of local and federal governments allowed products and by-products to be moved out of this quarantined zone and into multiple market areas, as far south as Guatemala (Figure 2).

The H5N2 low-pathogenic AI Mexican virus also found its way into Guatemala in the late 1990s via illegal movement of by-products, specifically heavy spent hens. At the beginning of this outbreak, the government established a mandated gag order; no-one was to make public statements to the press under the excuse it was to prevent panic in the general population. If disobeyed, likely retaliatory actions from the government would follow, like those occurred in the mid 1990s.

Government also reported introduction of this virus into the commercial industry was caused by migratory waterfowl, although the only previous isolation of an H7N3 AI in Mexico occurred in 2006 about 400 kilometres south-east of the quarantined zone. This is a very poor temporal and spatial association. Further, the first three commercial laying farms reporting the outbreak in Jalisco are all within a few metres of the main and only highway connecting the original (undisclosed) diseased broiler breeder farm and the local spent hen processing plant located about 200 kilometeres away to the north-east. Today, Mexican government continues to place blame on migratory wild birds.

The cost of this outbreak from June to the end of 2012 was US$750 million; half a billion dollars in direct costs alone from mortality of somewhere between 22 and 27 million layers and from loss of egg production. As reference, the high-path AI outbreak in Pennsylvania, US, in 1983 had direct cost estimates of $62 million and the same figure for the outbreak in Virginia in 2002 was $140 million.

*

"Low-path AI in Mexico has represented an average direct cost to the local poultry industry of US$246 million annually over the last 18 years, or a cumulative $4.4 billion."

It is both shocking and dazzling to know these were the same parties that allowed low-pathogenic AI H5N2 to become endemic throughout the country since 1995 after a high path H5N2 outbreak was eventually corroborated in the central state of Hidalgo in the spring of 1994. This virus, however, had been circulating in commercial poultry since the fall of 1993 but remained unidentified first and then covered up; the former because of ignorance and the latter in an effort by the government to save face after its presence had been repeatedly denied to international organisations like OIE and FAO.

Low-path AI is seldom discussed in open forums but its impact on live production parameters is well recognised amongst Mexican production veterinarians and company owners alike.

Low-path AI H5N2 in Mexico has demonstrated a predictable pattern from its consistent behaviour in sickening flocks, varied in severity only by season, altitude, confounding infections or vaccination status.

During the last meeting of the AAAP (American Association of Avian Pathologists) in Chicago in July 2013, it was presented how the cost of this prevalent low-path AI breaks down. Altogether and using conservative estimates, low-path AI in Mexico has represented an average direct cost to the local poultry industry of US$246 million annually over the last 18 years, or a cumulative $4.4 billion.

The Mexican market has been rewarding enough for some producers to believe low-path AI eradication is not really necessary, especially if eradication would mean the forfeit of income from affected flocks, at least for some time and without any type of indemnity. There is no will amongst producer to do so because they believe no-one else would act responsibly and follow.

Today, the director of animal health was then director of laboratory surveillance; today, the director of sanitary campaigns was then director of epidemiology and the list goes on. It is evident these members of government entrenched in their posts just never learned the lesson and basically limited their recent actions to the same, proven failed, interventions of the past.

Fifteen months after the first announced H7N3 outbreak, at least eight more episodes have been reported and many more have remained undeclared.

The virus is practically endemic in central Mexico now and given the striking similarities between the two different AI episodes, it is not only possible but also likely AI H7N3 will end up being a common occurrence in chickens throughout Mexico in its low path form. For example, states where low-path H5N2 is endemic account for 84 per cent of the broiler and layer industries combined although the government admits to only 30 per cent in its animal health web page.

Presence of Newcastle Disease Complicates the Picture

The two avian flu viruses will now share the spotlight with yet another virus demonstrated to be endemic in the country as well and whose presence continues to be denied by the Mexican government, namely velogenic, viscerotropic Newcastle disease (VVND), according to Dr Mirandé.

Continuous outbreaks of VVND are not only ignored by the government but are also actively concealed from the public eye in order perhaps to preserve an already meagre chance to Mexico becoming a poultry-exporting country. This denial is represented in the last map of the government’s animal health web page.

The VVND outbreak in Mexico in 2000 was the costliest ever recorded until last year, giving Mexicans the mark for the top two most expensive poultry disease outbreaks in history.

Challenges in 'Doing the Right Thing' on Reporting and Transportation

This should be sufficient to recognise there are other factors besides Mother Nature, writes Dr Mirandé, namely a corrupt system that allows poultry diseases into the country and then to spread out of control. Mexicans have been incapable of dealing with animal disease responsibly and this includes both the government and an industry in complicity to cope.

It is simple - no one wants to be the first to lose money by self-declaring a disease and do the right thing, like euthanising birds and burying them on site together with the manure when others simply will not follow.

Along the same lines of denial, the Mexican government does not recognise the presence of Salmonella enteritidis (SE) in its 140 million plus commercial layers or nine million plus broiler breeders and it has, for 20 consecutive years, rejected requests from various vaccine manufacturers to register a commercial SE bacterin on the pretext that there is no need for such request.

This corruption seen in the control of animal disease is not exclusive to poultry. Just last April, the Mexican Ministry of Agriculture announced it was prohibiting importation of shrimp from countries where a new, devastating disease is destroying entire industries by killing shrimp larvae, such as China, Viet Nam and Thailand, etc. This disease is caused by a vibrio and is called EMS or Early Mortality Syndrome (acute hepatic-pancreatic necrosis). By June, EMS was already wiping out many Mexican shrimp farms in the state of Sinaloa costing this industry close to US$200 million in as little as three months. This disease took three years to travel from Thailand, where it originated, to China, yet it took only two months to travel from China to Mexico and currents in the Pacific Ocean do not support such migration. It is now painfully accepted that an illegal cargo of contaminated shrimp was smuggled from China into Mexico, thus bringing this disease into local farms. This could have only happened with the bribing of Mexican port authorities in the state of Sinaloa.

Reasons for this demonstrated inability to control and eradicate disease are many and after living and working in this industry for nine years and experiencing substantial frustration when attempting to prevent and halt poultry diseases, Dr Mirandé says he has drawn his own conclusions.

Government corruption at all levels is the main culprit but also industry’s willingness to play that game under the assumption and acceptance that producing with inefficiencies due to health issues is still a profitable business. There is an embedded stigma that only with the support of indemnity funds a poultry operation should do all the right things.

During the early stages of the low-path H5N2 AI outbreak, a system of certificates of mobilisation was created in 1995 in order to ensure products and by-products from regions suffering AI outbreaks could not be transported into regions free of the disease. The country was classified by state into three categories based on their AI virus status: 'Control', 'Eradication' and 'Free'.

Tremendous pressure from states in the 'Control' and 'Eradication' areas was placed in order to allow commercialisation of their products, leading to the creation of several false AI-free status based more on political lobbying and influence from politicians and producers than their true AI virus status.

The money from such certificates, approximately US$8 (MXP100) per vehicle, would be used for indemnification of affected flocks.

Typically, in Mexico, 10 million live broilers are transported into Mexico City’s metropolitan area every week. Additionally, live heavy spent hens are transported to southern states, where this by-product carries a premium as it is considered almost a delicatessen. Thirdly, broiler litter is carried to the northern states, where it is used as a common feed ingredient for beef cattle.

Bottom line, within a few months after the certificate programme started, a small bribe of US$8 per certificate would have a federal employee of the Ministry of Agriculture signing these certificates permitting any mobilisation into any region.

No money generated from this programme was ever made available for indemnification of affected flocks. The potential annual value of these certificate bribes throughout the country is estimated today to be around US$7 million as there would be approximately 865,000 mobilisation certificates issued every year.

Vaccination Issues

Another example is the unprecedented and mandatory surcharge to the H7N3 vaccine of, again, US$8 per 1,000-dose bottle, paid to the federal government through the office of the Producer of National Veterinary Biologicals (PRONABIVE). This represents a potential US$19.4 million per year based on the number of vaccine doses already sold for H5N2 AI (Figure 3), according to Dr Mirandé.

Furthermore, the price charged to vaccine manufacturers for the official H7N3 master seed virus of duck origin is 10 times higher than that paid for the master seed of the traditional H5N2 killed vaccine and there is simply no valid technical reason for this action.

Again, reasons given are to establish an indemnity fund and to support research on this virus. Dr Mirandé suggests that no producer will ever see a penny from such fund and we have yet to see any research conducted on the same after 16 months.

There is still no permit to allow manufacture of a three-way product including both types of endemic AI viruses with Newcastle disease virus, which would be the logical product of choice in central Mexico.

There is no permission to manufacture a two-way product that includes both AI viruses either.

This illogical decision forces producers to inject birds multiple times, obviously increasing labour costs and affecting growth rates and uniformity from excess handling.

In Dr Mirandé's opinion, there is a clear pattern for the government to profit from this outbreak rather than to protect the economic interests of Mexican poultry producers.

Bureaucracy and technical inadequacies are also to blame. Some of these technical shortfalls are deliberate in order to maintain a system that has allowed many members of the Secretary of Agriculture, at all levels, to receive extra income by simply looking the other way when movement of products and by-products from areas where the virus is present in a majority of flocks takes place. These practices directly and specifically prompt the spread of avian influenza.

Along the same lines of senseless decisions, we have the one allocating manufacturing of the new killed vaccine originally to only three laboratories but reception, storage and sale of this vaccine to only one company in the region.

One can only speculate on the reason for the decision but we know that endless queues of many hours were seen for producers to be turned down at the end of the day with the explanation that some large producer had purchased all bottles available. A yet another opportunity for corruption was created.

More, the government decided that all vaccine would be produced in identical bottles and carrying the same PRONABIVE label, losing any identity as to the manufacturer. Producers buying this vaccine have no say on their preferred manufacturer - another unprecedented decision.

There has been speculation that reported vaccine inefficacy - officially explained as improper vaccination technique - could be due to poor vaccine quality since there is no brand recognition that encourages manufacturers to ensure a good quality emulsion with sufficient antigen content.

This is a real possibility with serious consequences. Whether poor vaccine quality or an untimely change in virus antigenicity is to blame, there are many reports of vaccine failure even in birds with multiple doses. Some producers are now injecting 1-ml doses instead of the normal 0.5-ml dose and up to four times in replacement pullets, both light and heavy. This is the equivalent of eight doses, considerably increasing the cost of disease control.

To be fair to the new administration of the Ministry of Agriculture, sworn in less than one year ago, the Secretary’s speech on 11 September 2013 declared that it will focus on eliminating 'a series of laws and regulations that do nothing to increase productivity but favour an environment of corruption at all levels of the Ministry'. He did not refer to poultry in particular but at least this could be a positive start.

There is also a cultural disposition to reject scientific and technical suggestions made from other countries with advanced industries, particularly from the US, as a misconstrued form of national sovereignty, says Dr Mirandé.

There is a series of flaws and systematic inconsistencies in the policies affecting animal health that illustrate why the eradication of this and other diseases is practically impossible under established practices. For example, since 1998 and in an action without precedent, it became illegal in Mexico for an individual, private institution or university to extract any type of biological material without a special permit; a permit that is never granted. Only the government in the office of the director of animal health has that ability.

As a result, knowledge on the genetic make-up, pathogenesis, evolution, etc., of Mexican avian influenza viruses stopped 15 years ago. The Mexican government has not published or verbally disclosed any information on more recent isolates and, although it does mention on its web page that the virus is prone to continuous genetic change, it did not allow the update of the killed vaccine master seed until last year - 18 years after the original master seed was developed.

Commercial vaccines were already ineffective by the early 2000s and vaccine manufacturers, at the request of producers, illegally started manufacturing autogenous or commercial AI vaccines with more recent isolate since 2004 without disclosure.

Future Impacts on Poultry Trade

As the US industry enjoyed a record profit year in 2013 - assisted in no small part by record exports of chicken meat and hatching eggs to Mexico - it should stop and re-evaluate if this extensive trade with its southern neighbour represents a risk of introducing the disease, according to Dr Mirandé.

Just how cautious or worried should the US industry be? The lines of candid communication between the two commercial partners, whether at the government or private sectors, must be much improved.

Little of what is published or stated in official forums regarding poultry diseases in Mexico is true and that is not the behaviour expected from a modern and civil democracy and the 11th World economy.

It is not hard to think of ways for any of the aforementioned viruses to enter the American poultry supply chain and they must be properly identified and effectively avoided. Ignorance of scientific facts or current status of AI in Mexico could easily translate into xenophobia and even racism, as the US poultry industry depends on a workforce with repeated entries into Mexico and back.

There is considerable variation in the approach taken by poultry companies regarding personnel when traveling to Mexico, more so if direct contact with live birds is involved, such as personnel working in vaccinating crews, for example. Whether using own crews or contractors, decisions must be based on sound science, truthful information and logic to avoid discriminatory labour practices already observed in several operations that could bring legal consequences.

In the United States, it appears the determination to keep diseases out of their flocks is only as strong as their memory. In the past, some companies have made the decision to vaccinate breeder flocks in a complex in lieu of mandatory depopulation according to NPIP (National Poultry Improvement Plan) after Mycoplasma gallisepticum (Mg) is diagnosed. The justification has always been that such particular Mg is mild and does not cause clinical disease in broilers. In 2013, the US showed a record high number of Mycoplasma synoviae (Ms)-positive broiler breeder flocks and also several companies decided not to slaughter them as indicated in NPIP.

This was motivated by an unusually lucrative business of exporting broiler hatching eggs into Mexico for record prices - up to more than double the normal.

If severity of disease (or lack of) and income present the right combination and decisions like this become the norm, could the next sub-clinical low-path AI-positive flock be allowed to co-exist?

With a greatly diminished, although already accustomed productivity in the Mexican poultry industry, an obvious loss of exporting privileges and the imminent risk of disease introduction into the US industry, it is confirmed that a new approach to the control of poultry diseases in the most important trade partner to the US is long overdue and must be demanded at the appropriate platforms.

The system has been uncovered and it must be terminated, even if it is only on the basis of public outrage and international embarrassment.

Solutions: the Way Ahead

Dr Mirandé proposes the six basic steps to start the path out of this mess:

- Reclassify without commercial or political prejudice the true AI status by poultry region and not by State and reassess after each year.

- Must stop all transport of any live birds or litter from AI positive flocks outside your complex.

- Mandatory vaccination for two years in all birds in regions where the AI virus is present, whether demonstrated by serology, virus isolation or a DNA-based rapid test, without losing the ability to sell product as long as the same has been processed through a federally inspected plant. Reassess AI prevalence after each year of compulsory vaccination.

- Absolute prohibition to move live birds and/or broiler litter or layer manure out of an AI positive zone. These high risk products should be consumed within its own zone. Products processed through a federally inspected plant can be sold outside its own region. Litter from AI positive flocks should be composted in-site and never hauled.

- Recover or demand the funds generated through the certificate system over the last 18 years to pay indemnity of affected producers, the way it was originally created for.

- Independent, unbiased oversight committee of respectable people beyond the reach of bribery that allocates indemnity funds based on, among other criteria, demonstrated responsibility of self-reporting disease and actively limiting its spread.

It is time for the Mexican poultry industry to recover its efficiency and ability to compete with other progressive industries throughout the World.

Short-term losses will be compensated, not by an indemnity fund but rather by long-term performance improvements that could eventually translate into what it should have always been, a country exporting its poultry products to many places around the world.

Chile has some of its products on US and Mexican shelves and is ranked 25th in broiler meat production because there is confidence in that country's clean sanitary status. Mexico ranks fifth and has no broiler meat products in the US or Chile because nobody believes in its official sanitary status.

It has been so long since a majority of Mexican flocks of broilers and layers were AI- and/or VVND-free that many producers have forgotten what a truly healthy flock looks like and how it should perform.

Perhaps this is the reason they appear to have lost the desire to obtain a true disease-free status. Dr Mirandé concludes that the time is right for action to get it back.

February 2014