Innovation in Layer Housing: From Drawing Board to Reality

The Roundel laying hen house is an example of successful innovation in agriculture between researchers, farmers and the wider community. Jackie Linden reports on its development from the drawing board to successful sustainability in the Netherlands.One of the concepts in hen housing put forward by Wageningen University in 2008 was thought to be too risky ever to become commercial, but Willy Derks is the owner of one of the three systems now in successful operation in the Netherlands.

In a presentation to the Innovative Farming conference organised by Innovation for Agriculture and Animal Task Force at the UK’s National Agricultural Centre last week, Mr Derks explained that the Wageningen project had started in 2004 with the aim to create a housing system for egg production that fitted the needs of the farmer, his chickens, his customers and society in general – in other words, a fully sustainable option for laying hen husbandry.

Seven years ago, two possible designs had been completed on the drawing board but then the project stalled until the Venco Group accepted the challenge to being the Roundel house to reality in a partnership with the University, a farmers’ organisation in South Holland (ZLTO) and TransForum.

One of Venco’s businesses, Vencomatic, set up a new division, Roundel, which not only builds the barns but also markets the eggs.

The first Roundel house (Rondeel in Dutch) was constructed at Barneveld and there is a mini-version on the outskirts of Amsterdam, which informs local people about the concept as well as selling eggs.

The third Roundel is at Ewijk, near Nijmegen. Run by Mr Derks with one full-time and one part-time worker, it is now on its third laying flock of 30,000 hens.

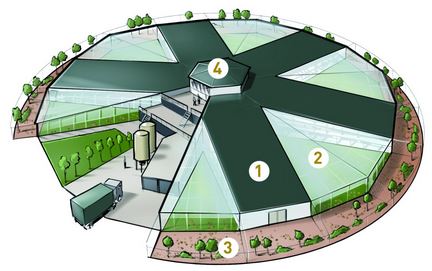

The Roundel Housing System

In the central core are the working area with egg-packing facilities on the ground floor, with a visitors’ area above and the top floor houses the heat exchangers for the ventilation and manure-drying systems.

Around this is a series of five “wedges”, each with a standard aviary where the birds can eat, drink, perch and lay and where they spend the night.

In the morning, the curtain sides are raised to allow them access to the day quarters, a covered area of artificial grass where they can forage and dustbathe in natural daylight.

One of the daytime areas has a tunnel offering visitors to the farm a bird-level view of the operation. This is open to the public every day from morning until dusk.

Around the outer five- to six-metre wide perimeter of the building is the “wooded area” - a natural area of wood chips and natural tree trunks where the hens can perform more of their natural behaviour.

Here, the outer sides are chain-link fencing and this area is covered with a roof that can be rolled back during fine weather. The wooded area can be closed off in case of the threat of a disease such as avian flu.

As Mr Derks explained of the Roundel: “Nature has been brought inside.”

Sustainability at the Heart of the Roundel Concept

Hen welfare is at the very heart of the Roundel design with the varied environments within the building to allow them to perform their natural behaviour.

Feed, water and perching are accessible all the time in the night quarters. Stocking densities are 12 birds and six birds, respectively, per square metre during the night- and daytime, respectively – higher than free-range but lower that other systems based on housing.

Mr Derks commented that none of his flocks has been beak-trimmed and feather-pecking has not been an issue. Even towards the end of lay, the birds have full feather cover.

Laying performance has been high for all three of Mr Derks flocks and mortality has generally been low. A small peak in mortality linked to E.coli in his current flock was thought to be linked to unusual weather and egg laying and health soon returned to normal, such that the birds have so far laid an average of 317 eggs (to 75 weeks of age).

There is one climate in the whole barn, he said. Roundel is naturally ventilated, with fresh air coming in through the sides, rising along the sloping roof of the day- and night-quarters and into the top storey of the central core, where outlet vents open automatically away from the prevailing wind to encourage air flow, whatever the weather conditions.

Turning to the environmental aspects, the Roundel uses little energy owing to the natural ventilation system and widespread use of daylight.

Twice a week, the manure from the unit is dried to a valuable 80 per cent dry matter fertiliser using the energy from the sunlight through the roof and the birds themselves via heat exchanger.

Economics of the Roundel System

Economic sustainability is, of course, vital to the future of the Roundel system.

Eggs are packed in specially designed biodegradable boxes containing seven eggs and marketed through the Roundel organisation to a number of organisations across the country, including supermarket chain, Albert Heijn, specialist restaurants and the national airline, KLM.

At around €75 per hen place, the Roundel system is around two and a half times more expensive to build than the same size of unit with colony cages in the Netherlands, according to Mr Derks.

However, Roundel farmers know the price they will receive for their eggs throughout the flock’s life; the price is adjusted only in response to fluctuations in the feed price. The current price received by the farmers is around 28 Euro-cents each, which represents a significant premium over barn eggs, according to Mr Derks and is between the producer prices for free-range and organic eggs.

Spent hens at the end of their productive lives are sold to the catering side of KLM to make chicken sandwiches for its European flights.

Under the system, he explained, Roundel Ltd is responsible for sales of the housing systems in the Netherlands and the rest of Europe, national egg sales and it supports investors. The farmer is the franchisee, caring for the hens, egg-packing, local eggs sales and organising the use of the visitor areas.

Corporate social responsibility has always been an important consideration for the Roundel system, which has received approval from the Dutch animal welfare organisation, Wakker Dier.

Roundel farms remain popular with visitors, many of whom buy their eggs there. The consumer organisation, Beter Leven (“Better Living”) has awarded the system three stars for animal welfare and Roundel is the only egg system to have been recognised for its environmental credentials by Milieukeur.

It is clear that Mr Derks is convinced about the strengths of the Roundel system for egg production in the Netherlands.

The British audience at the event were impressed by the concept, the high level of production and absence of feather pecking/cannibalism issues in these non-beak-trimmed birds.

After the EU ban on conventional battery cages in 2012, the majority of Dutch egg producers turned to enriched/colony cages or barns (aviaries), while UK farmers embraced free-range systems, which now account for 45 per cent of the shell egg market and the new cages (52 per cent).

This difference in approach may explain the continuing success of the Roundel system in the Netherlands – where another house is due for completion later this year.