Marathon chick

By Ron Meijerhof, Senior technical specialist, Hybro B.V. and published in International Hatchery Practice Volume 19 Number 5, 2005 - Supplying energy to a developing embryo is a critical process in incubation. To fully understand its impact, we need to look closely at sources of energy and how they are used.

We can compare incubation with running a long distance marathon, to help visualise what is actually happening. The developing chick, like the marathon runner, uses two main sources of energy: carbohydrates and fat. For the embryo, fat is stored in the yolk, and carbohydrates in the yolk and albumen. For the marathon runner, carbohydrates are stored primarily in the liver and blood, while fat is stored in fatty tissues.

During the first part of a marathon, the athlete uses carbohydrates as fuel – as they are easily accessible and supply a quick energy source. Using carbohydrates requires oxygen - and produces carbon dioxide, metabolic water and heat as waste products. This heat forces the runner to sweat, increasing heat loss, and increasing body temperature which will, in turn, increase the ‘burn-rate’ of carbohydrates by the body.

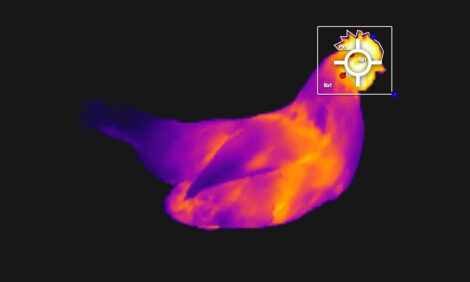

During early incubation, the embryo also ‘burns’ carbohydrates, using oxygen as energy, to produce carbon dioxide, metabolic water and heat, just like the athlete. This heat production forces the embryo’s temperature to rise above air temperature in the second half of incubation.

After a certain distance, when the carbohydrates are used-up – the body should turn to its fat for energy. However, carbohydrates are needed to utilize fat - which is why athletes don’t start a race too fast, as they run out of carbohydrate energy too quickly.

A chicken embryo too must utilize fat energy in the second half of incubation, normally from around day 14. However the embryo also needs carbohydrates to access fat. Research indicates that by this stage, the embryo – like the athlete - has used its carbohydrates under increased temperature conditions, and faces the same challenge for accessing its fat sources for energy.

Hitting ‘the wall’

When the athlete runs too fast too early, he or she will “hit the wall”: all the energy is gone, everything hurts and it is almost impossible to continue running. The body still has plenty of body fat as reserve energy, but no carbohydrate ‘key’ with which to unlock it. If an athlete can find the mental power to continue running, the body will find protein before fat as an alternative energy source. That means burning muscle tissue, including the heart – which of course, can lead to serious, long-term damage.

Similarly, when incubation temperature is too high, the embryo cannot access yolk-fat without carbohydrates. However ambient conditions dictate an embryo’s body temperature, as it is incapable of regulating its own temperature, and without access to fat - it too will have to use muscle tissue as an energy source, which probably accounts for the decreased development, increased yolk residue and poor performance we see with over-high incubation temperatures.

An extra complication is that embryos will use the glycogen stored in the liver to provide energy for hatching, simply to survive high incubation temperatures in ovo – but then lacking the energy for hatching. Restoring that glycogen source by injection to the amnion will help the embryo, but careful control of embryonic temperature avoids the need for this type of intervention, as well as reducing costs.

For embryos, the incubation process is like a demanding sport. We can’t train embryos to prepare them for their own form of marathon, but we can incubate them in conditions that allow them to finish their race well – and the key to delivering their best form, is to carefully control temperature throughout incubation.

Source: Hybro B.V. - October 2005