Necrotic Enteritis

By Stephen A Lister and published by DuPont Animal Health Solutions - Necrotic enteritis was first described in chickens in England in 1961. Since then it has been reported in most poultry producing countries around the world. Early workers reproduced the disease by infecting chickens with the bacterium Clostridium welchi (now known as Clostridium perfringens).What is Necrotic Enteritis?

The condition occurs sporadically, mostly in broilers, but may also be seen in commercial layer pullets and turkeys. The most common clinical sign is sudden death and, in an acute outbreak, can mean a 10 per cent mortality. In less severely affected birds, or during mild outbreaks, birds are depressed, inappetant and may have diarrhoea. The picture is, in many ways, similar to a low grade coccidiosis outbreak .

As its name suggests, the condition is characterised by the death or necrosis of the intestinal lining, predominantly of the upper small intestine. Here, clostridial bacteria produce large amounts of damaging type C toxin which, when combined with digestive enzymes, destroy the lining of the gut.

Trigger factors

In healthy chickens, these clostridial bacteria normally live harmlessly in the lower gut, and are found in the caeca and lower large intestines. The pH and high oxygen content of the healthy small intestine do not support growth of the organisms. So, for necrotic enteritis to occur, there needs to be a trigger factor that tips the balance in favour of the clostridial bacteria, allowing them to proliferate and migrate to the upper intestines.

What are the important factors?

A number of factors may be predisposing to this proliferation:

-

Direct damage to the intestinal lining by coccidial challenge or bacterial overgrowth.

-

Feed factors which alter the gut environment and pH. These may be associated with different feed types such as rape, fish meal or wheat, or with changes in nutrient density - for example, protein levels.

-

Immunosuppression, which reduces resistance to gut infections. Immunosuppressive agents such as chick anaemia virus , Gumboro disease or Mareks disease , or more general physiological stress, may all be factors.

-

Physical factors which damage the gut lining, for example, the effects of intestinal impactions with litter, a lack of grit, or changes in physical feed presentation.

Treatment

Severe clinical outbreaks usually respond to specific antibiotic treatment, most effectively with amoxycillin via the drinking water. In outbreaks where there is a significant coccidial challenge contributing to the gut damage, specific treatment with an anticoccidial drug in the water may also be required.

Control

To prevent an outbreak of necrotic enteritis, the aim is to maintain a healthy, stable gut environment. Prevention of subclinical coccidiosis challenge is probably the single most important aspect. This can be achieved by reducing the weight of challenge on the birds by preventing environmental build up of coccidial oocysts.

This is done by:

-

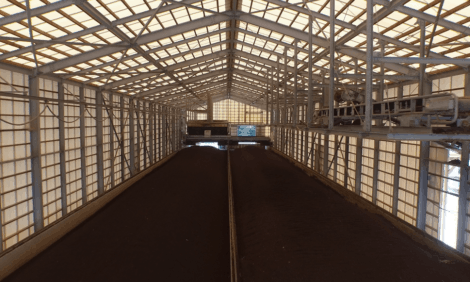

Effective terminal cleansing and disinfection combined with a specific oocidal disinfectant. There is, in fact, only one disinfection product which has proved effectively to eliminate oocysts (OO-Cide, DAHS International) by penetrating the very tough outer walls of organisms which otherwise prove stubbornly resistant to cleaning and disinfection. OO-Cide can be used as a primary control method in units.

-

Maintenance of good working litter.

-

Inclusion in the feed of anticoccidials (especially ionophores) and digestive enhancers, which will also suppress bacterial overgrowth in the intestines.

Gut activity can also be upset by sudden changes in diet specification and feed presentation, and these should be avoided.

Immunosuppressive viruses may adversely affect the performance of the gut defences which normally prevent damage by coccidia, clostridia and other bacteria. Effective virucidal cleansing and disinfection will help to reduce the influence of such viruses. Both at terminal disinfection, and in daily biosecurity regimes, products which offer broad spectrum efficacy and safety in use are to be preferred. For example, Virkon 'S', DAHS, is a broad spectrum virucidal disinfectant which also has proven efficacy against bacteria and fungi, but which, at the correct dilution, is also safe to use in water lines and even as an addition to the drinking water.

Conclusions

Necrotic enteritis can cause significant mortality in broilers in their rapid growth phase. This can lead to loss of birds, deterioration in litter quality and an adverse effect on broiler performance.

The condition occurs when clostridia gain the upper hand and equilibrium of the gut environment is upset. Inclusion of ionophore anticoccidials and effective digestive enhancers will help to ensure gut stability, whilst attention to site cleaning and disinfection, and general biosecurity, will contribute to a reduction in significant bacterial, parasitic and viral challenge.

Further Reading

See Our Quick Poultry Disease Guide on Necrotic Enteritis

Source: DuPont Animal Health Solutions - Taken From Site November 2005