Recognising and Preventing Naval Yolk Sac Mortality

By Hybro B.V., Boxmeer, The Netherlands - In every flock, we usually find increased mortality around 3-4 days of age - and if we examine possible causes, we often find a significant number of birds have died of navel-yolk sac infection or 'omphalitis', often associated with e-coli infections or other bacterial contamination.

Causes are widely recognised as poor hatchery hygiene, poor hatching egg quality, poor nest sanitation or condensation on the eggs. The inclusion of floor eggs or washed eggs in the setter can also contribute to this problem.

Common causes of first week mortality

In the case of poor egg hygiene or shell quality, the bacterial load on the eggs is increased, therefore

placing greater pressure on the natural defence mechanisms of the egg and the chick. If bacteria get

the upper hand, the chick will die from the resulting infection.

However, we also see naval-yolk sac mortality where there is very good egg quality and proper hygiene

procedures in place. This is because bacterial pressure is by no means the only determining factor:

the chick's ability to utilise its natural defence mechanisms is also critical.

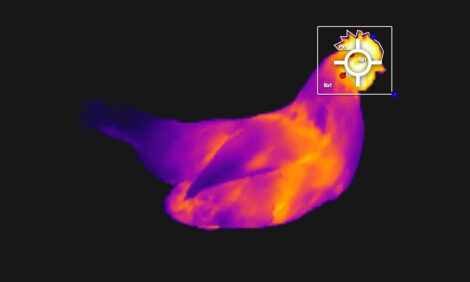

Naval closure reduces mortality

If the navel is still open when the chick is hatching, or when tissue is stuck in the navel after closing, it is very easy for bacteria to enter the body cavity, so infecting both the navel and the yolk sac. And while there are several aspects involved in the closure of the navel, the most important factor is believed to be temperature during incubation.

High temperature navel deformity

When temperature during the last half of incubation is too high, the chick will be unable to convert yolk

efficiently for its development, which results in the chick having a small body with a relatively large -

and therefore difficult to absorb - yolk. Because development is impaired due to high temperature, the

chances of the chick hatching with the navel not yet properly closed are greatly increased.

As a result, the navel will show a black button (dried blood and tissue) and there will be blood in and on

the shells in the hatcher trays. With these obvious signs of open, bleeding navels during the hatch, the

potential for infection is high.

Low temperature navel deformity

Equally, when temperature at the end of incubation and at the point of hatch is too low, the uptake of

yolk and closure of the navel will not be completed before the chick pips and hatches.

This low temperature may be directly due to incorrect machine temperature set points. But it can also

be due to erroneous humidity or ventilation control. Humidity control must take into account the natural

humidity created by the chicks, as approximately 3 grammes of water evaporates in the first 15

minutes after hatching. Equally in ventilation, we must warm incoming air sufficiently to ensure that the

chicks do not become too cold.

If temperature at point of hatch is too low, this will also result in poor navels and blood in and on shells.

Overcoming navel-yolk sac mortality

As a general rule, when we see black navel buttons, it is likely that late-stage incubation temperature

was too high - and with string navels, that temperature at point of hatch was too low.

Whenever we face structural problems with navel-yolk sac mortality in the field, we should first

examine the quality of hatching eggs, to ensure that bacterial contamination is reduced as far as

possible. But it is also important to understand that, even when optimum egg quality is present,

navel-yolk sac deformity due to overly high or low temperatures in the incubator will result in infection -

and often mortality - if we don't optimise the incubation process.

Source: Hybro B.V. - January 2006