Study Examines How to Integrate Poultry with Pasture Species and Agroforestry Production

Researchers at the USDA-ARS at the University of Arkansas report on their investigation into alternative feeding systems, parasite control and pasture enrichment for free-range poultry combined with pasture, cattle and agro-forestry systems.With the right tools for alternative feeding systems and pasture enrichment, farmers can successfully incorporate poultry into free-range, multi-species pasture or agroforestry production, based on the results of a USDA-ARS Arkansas study.

The Southern Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education (SSARE)-funded project (LS10-226), 'Integrating Free Range Poultry with Ruminant and Agroforestry Production in a Systems Approach', looked at the various ways pasture can be used as a resource in ecological poultry production.

“In ecological poultry production, using a pasture resource effectively can be key to sustainability. You can use the pasture to its full benefits, but the challenge for farmers is to know how to do it,” said Dr Anne Fanatico, an assistant professor at Appalachian State University in North Carolina.

Dr Fanatico conducted the research when she was a research associate with the USDA-ARS Poultry Production and Products Safety Research Unit at the Center of Excellence for Poultry Science at the University of Arkansas.

She and her colleagues looked at alternative feeding systems, parasite control and pasture enrichment.

Dr Fanatico said: “When integrating poultry with other animal species on pasture or agroforestry systems, high-quality forage can be an important source of nutrients for poultry, but the birds also need a concentrated source of feed, particularly energy feed because they do not ferment fibre like ruminant animals do.”

The researchers studied two feeding systems: free-choice feed and choice feeding as an alternative to fully formulated diets that can make use of the pasture resource.

In free-choice feeding, also known as “cafeteria-feeding”, feedstuffs are offered separately to birds, such as grains, protein concentrates, vitamins and mineral sources, so they can self-select a diet suited to their changing needs.

“Feed is a high cost, particularly for organic and small-scale producers,” said Dr Fanatico. “Free-choice feeding may offer cost savings, including the use of on-farm ingredients, reduction in feed transportation, and milling costs.”

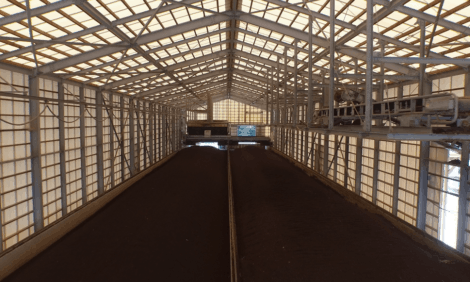

Photo credit: Arkansas State University

In the study, chickens were randomly assigned one of two treatments: fully formulated or free-choice diet. Researchers found that crude protein was lower in the free-choice diet (13.2 per cent) than the fully formulated feed (20.75 per cent) and breast yields were high in birds fed the fully formulated diet. However, the free-choice diet was less expensive and final live weights did not differ between the two treatments.

In choice feeding, the birds typically choose between two feeds: a protein concentrate and a grain.

Dr Fanatico explained: “Choice feeding may allow birds raised in relatively open housing with largely uncontrolled environmental conditions to more precisely meet their nutritional requirements by self-selection compared to a fully-formulated diet.

“Choice feeding may also allow producers to use feed grains produced on their own farms in order to reduce transportation and milling costs.”/p>

In the choice feeding studies, researchers found that birds on a fully formulated diet gained more weight than those on a choice feeding diet. However, feed efficiency in the choice feeding diet was greater and was less expensive.

Researchers also studied various forage needs for poultry, such as chicory, soybeans and sericea lespedeza. Forages low in fibre are best for poultry, said Dr Fanatico.

In addition to feeding and forage, Dr Fanatico and her colleagues looked at the enrichment of outdoor areas in pasture and agroforestry systems to encourage birds to more actively obtain nutrients, spread manure and reduce heavy use around the poultry house.

She said: “Pasture is an important resource for poultry. What good is it if they don’t use it. So we wanted to look at various ways of drawing them out into the yard by simulating agroforestry structures.”

Researchers incorporated enrichment elements such as roosts, screened shelters, branches and other elements to provide shade and protection. They found that birds introduced to pasture with those constructed enrichments foraged more, used the pasture more fully and moved further away from poultry houses.

Lastly, researchers studied the prevalence of parasites in both livestock and poultry when integrating free-range poultry with small ruminants, cattle and swine. They found that sericea lespedeza, which is found to be effective in small ruminant parasite control, had little impact on broiler parasites. Also, when evaluating Campylobacter and Salmonella parasites in poultry in integrated cattle and swine systems, findings were mixed.

Dr Fanatico explained: “These findings indicate that system-level research is needed to evaluate the safety of food products in integrated livestock production. But there are many ways farmers can integrate free-range poultry into grazing livestock operations on small farms that will aid in parasite control.”

Overall, the SSARE-funded study showed benefits of using the pasture resource and farm-raised feeds for free-range poultry production and integration with grazing animals. Increasing diversity on the farm is a key principle of sustainable agriculture, allowing for beneficial interactions, better resource use efficiency and microhabitat differentiation, better nutrient cycling with animals and enabling energy flow.

Dr Fanatico co-led the project with Annie Donoghue, research leader at USDA-ARS. Collaborators in the study included Jon Moyle, now a University of Maryland Extension specialist; Joan Burke, USDA-ARS Booneville; Clay Colbert of Little Portion Farms; Jennifer Edwards of Dancing Springs Farm; LSU professor Jim Miller; Will Lathrop with the Kerr Center for Sustainable Agriculture; and NCAT’s Margo Hale.

This article was published by the Southern Region of the Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) programme. Funded by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), Southern SARE operates under cooperative agreements with the University of Georgia, Fort Valley State University, and the Kerr Center for Sustainable Agriculture to offer competitive grants to advance sustainable agriculture in America's Southern region.

March 2015