The Phenomenon of 'Silver Backing' in Free-range Hens

Brown-feathered hens in Australia have been observed to conduct pecking behaviour that removes the coloured part of the feather, leaving behind its white base, giving rise to a 'silver-back' appearance. Mingan Choct (University of New England) and Michael Sommerlad (Poultry Works Consultancy) explore possible causes of this phenomenon in the latest issue of 'eChook'.The free-range sector of the poultry industry is expanding rapidly in Australia, now representing approximately 40 per cent of laying hens and 15 per cent of broilers. It is often perceived by the public that free-range birds enjoy better welfare status, and this view is heavily promoted by animal liberation organisations and the supermarkets.

The rapid expansion of the free range sector has introduced a number of issues for the commercial production sector. Firstly, free-range production has not been widely practised in Australia for many years, and many of the skills required to maintain viable production levels have been lost, with very few poultry professionals possessing the necessary knowledge and experience to assist this sector. The industry will have to re-adjust itself, and embrace the old husbandry skills that have been lost some 50 years ago. Along the way, there will be productivity losses through efficiency drops, biosecurity issues and environmental problems.

*

"The challenges of educating the public, the politicians and the interest groups would be immense for the poultry industry if it were to meet some of the demands of a society where there is a complete disconnect between agriculture and food production."

Secondly, the birds used in the free-range system today have been specifically bred for indoor production systems, which often leads to less-than-optimum performance when they are placed in a free-range system.

Professor Geoff Hinch at the University of New England used Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology to reveal that only about 15 per cent of hens go outside every day and 10.6 per cent of the hen population never go outside onto the range. Interestingly, 89.4 per cent of the hens used the outdoor range on at least one day over a 51-day experimental period. The distance that birds travel on the range also varies tremendously.

Thirdly, the public wants safe, cheap, fresh food produced sustainably and ethically. It is not hard to see the inherent contradictions in this thinking. The challenges of educating the public, the politicians and the interest groups would be immense for the poultry industry if it were to meet some of the demands of a society where there is a complete disconnect between agriculture and food production.

In this article, the authors touch upon one challenging area, i.e. welfare management. Indeed, welfare management is probably the most demanding issue because cannibalism is highly prevalent in free-range flocks and, in extreme cases, almost the entire flock can be affected (Sherwin et al. 2010). In this article, the authors look at the phenomenon of 'silver backing' rather than cannibalism as such.

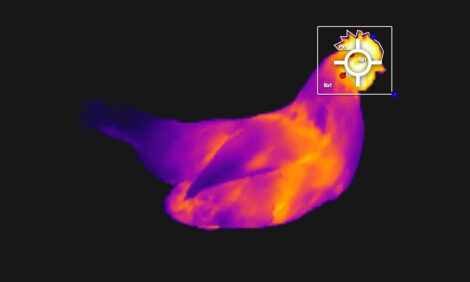

Silver backing is where free range birds look white along their backs and down towards their tails. The change in feather colours can start anytime from early lay to mid lay and become progressively severe (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2 (right): The same flock at 40 weeks of age

*

"The silver colouring results from the small, soft feathers from the backs of the birds having the brown tip."

This occurs even in the best free-range farms. The silver colouring results from the small, soft feathers from the backs of the birds having the brown 'tip' (see Figure 3) removed by a specific pecking action, leaving only the white base of the feather remaining (see Figure 4).

It is not like the classic aggressive vent pecking seen in the past in birds which were not beak-trimmed.

Silver backing occurs when birds develop behaviours that target the small feathers without inflecting any soft-tissue injuries. The same sort of behaviour is exhibited during dust bathing, where flock mates take small soft feathers from around the thighs. However, these feathers appear to be more easily removed from the skin, so rather than leave the white base behind, the whole feather is removed.

Figure 4 (right): The same feather with the brown tip removed by pecking, leaving just the white base.

The causes for this phenomenon are not known, and there are a range of theories on the various factors that lead to feather pecking behaviour (Rodenburg et al. 2013). It is thought that despite a relatively large range space available, some birds may get bored and constantly search for some activity to do in an environment where light intensity is high.

It is also possible that the birds may be deficient in dietary energy and nutrients, such as some of the essential amino acids and key minerals. This could well occur because, firstly, some birds spend a considerable length of time outdoors, searching for insects or seeds. The consequence of this could be the increased expenditure of dietary energy on physical activity and the lack of consumption of the balanced feed provided inside the shed or at the feed cart.

Secondly, when the season is good and the range is lush, some birds consume a large amount of long grass (see Figure 5). Unlike ruminants, the chicken does not have the necessary enzymes and microflora to digest the lignocellulose compounds that make up the bulk of grass dry matter. Instead, the grass is often coiled up in the gizzard, remaining un-ground (see Figure 6).

Figure 6 (right): Droppings of a hen that consumed a lot of grass.

There are a number of possible consequences of this:

- it might act as a negative feedback mechanism, reducing the intake of properly balanced feed

- it leads to gizzard impaction, causing decreased feed intake, and in extreme cases death from starvation, and

- this decreased feed intake may lead to the birds seeking more nutrient dense sources of specific nutrients, such as feathers or flesh. It is not known whether birds in distress are more prone to pecking at fellow birds or other objects.

One factor that appears to be constant with the phenomenon of silver backing is that the behaviour may be directly linked to the additional pressures placed on the birds by the onset of egg production, as silver backing is not normally observed in growing pullets. This observation would suggest that nutritional factors are at least a significant contributing factor to the condition.

In conclusion, with poultry products having become the staple protein sources for Australians, the sustainable supply of these products cannot simply rely on a traditional model of poultry production, i.e., a few chooks running free in the paddock to supply the family with some eggs and the occasional roast chicken.

The looming inability to provide adequate poultry products to meet the nation’s growing needs will directly affect its food security.

Poultry production of the future will require a massive amount of evidence-based research on husbandry, genetics, nutrition, welfare and environmental management.

Only through this work will we meet the challenge of establishing a poultry industry that produces quality protein in an affordable, ethical and sustainable manner.

References

Sherwin, C.M., Richards, G.J and Nicol, C.J. 2010. A comparison of the welfare of layer hens in four housing systems in the UK. British Poultry Science, 51(4): 488-499.

Rodenburg, T.B., Van Krimpen, M.M., De Jong, I.C., De Haas, E.N., Kops, M.S., Riedstra, B.J., Nordquist, R.E., Wagenaar, J.P., Bestman, M. and NICOL, C.J. 2013. The prevention and control of feather pecking in laying hens: identifying the underlying principles. World’s Poultry Science Journal, 69:361-374.

December 2013