Understanding the Hatching Egg

For many years, the hatcher was considered to be merely a ‘finishing’ machine.However, research undertaken by Petersime has shown that the hatcher can enhance and optimise what has already been achieved in the setter, resulting in gains in uniformity, quality, hatchability and post-hatch performance. This requires good programme management, writes Roger Banwell, Hatchery Development Manager at Petersime.

Below we provide two key elements that will help you get the most out of your hatchers.

1. Adapt your incubation programme according to the timing of transfer

Ideally, egg transfer from setter to hatcher is organised at day 18. However, for a series of practical reasons, in most hatcheries the time of transfer will vary between day 15 at the very earliest until day 19 at the very latest.

If you applied the same incubation programmes when transferring at, for instance, day 17 and 12 hours than you would apply when transferring at day 18 and 12 hours, you risk sub-optimal results. Why? In the graph below, you can see how the temperature of an egg evolves in the different phases of the hatch process: vascular activity (blood flowing to the outer membrane) (1), turning into position (2), internal pipping (3) and external pipping (4).

The simplified graph below shows key changes in the required environmental conditions.

From the graph, it is clear that transferring at day 17 and 12 hours will require very different conditions in the hatcher than those needed when transferring at day 18 and 12 hours.

2. Load only eggs from the same flock and age, with the same storage time and coming from a balanced setter

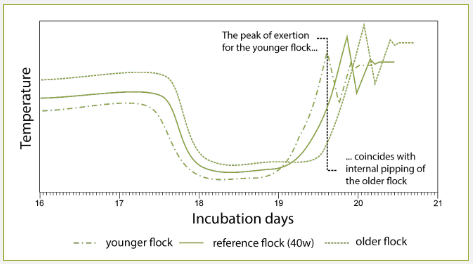

For different types of flock, ages and storage time, the overall profile as shown above will shift, and the intermediate durations and peaks will differ. If different flocks are combined, achieving optimal conditions becomes difficult if not impossible.

In the graph, the high heat production of the peak exertion period from the young flock with short storage times coincides with the internal pipping stage of the older flock that has been stored longer.

As a consequence, loading a uniform source into the hatcher is also essential in order to benefit from thermal and/or CO2 stimulation.

References:

- Vince M.A., Effects of external stimulation on the onset of lung ventilation and the time of hatching in the fowl, duck and goose. British Poultry Science, 1973, 14:4, 389-401.

- Tong A., McGonnell IM., Romanini C.E., Berckmans D., Bergoug H., Roulston N., Garain P., Demmers T., Effect of high CO2 during the final 3 days of incubation on the timing of hatching in chick embryos. CIGR - International conference of agricultural engineering, Valencia, Spain, July 8-12, 2012.