Viral Respiratory Diseases: Are They Ever Under Control?

In conjunction with the annual UK Branch meeting of the World's Poultry Science Association, The Gordon Memorial Lecture was presented last month by Professor Richard (Dick) Jones of the University of Liverpool. Jackie Linden, editor of ThePoultrySite, summarises the highlights of Professor Jones's lecture.

Southport, 31 March 2009

Viral respiratory diseases are an important cause of losses to the poultry industry," Professor Jones stated at the opening of his presentation for the Gordon Memorial Lecture, "because they cause reductions in growth rate and egg production, as well as increases in mortality and the represent additional costs of vaccinations and medications."

The group of diseases includes avian influenza and Newcastle disease but Professor Jones focussed on three diseases that he has most closely studied: infectious laryngotracheitis (ILT), avian metapneumovirus infections (aMPV) and infectious bronchitis (IBV).

Professor Jones went on to define the word 'control', for the purposes of his presentation, as 'restraining or reducing the prevalence of the individual diseases'.

Infectious Laryngotracheitis Virus (ILTV)

ILTV was first described as long ago as 1925. It produces only respiratory symptoms but with a range of virulence from per-acute to subclinical. It is a herpes virus of a single serotype. The host is the chicken – it is not found in turkeys – and it is usually found in older birds. The spread of the disease is slower than for other viruses. No wild bird reservoirs of the virus are known. The virus has become endemic in some parts of the world, e.g. US, Australia and possibly, the UK.

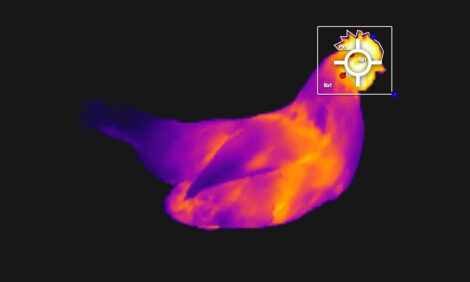

Diagnosis is confirmed at post-mortem with asphyxiation by caseous plugs, blood expectoration and tracheal intranuclear inclusions, as well as the detection of the virus.

Control is by live vaccination. Professor Jones explained that control is hampered by the reversion to virulence of the virus vaccines, reactivation of latent vaccine virus and the danger of mixing naïve birds with those that have recovered from the infection.

To date, single vaccinal types have been largely effective but Professor Jones raised the question of the importance of novel genotypes. "How important are they, where do they come from – given that there is no known wild bird reservoir – and will they evade the protection afforded by current vaccines?", he asked.

Avian Metapneumovirus (aMPV)

Compared to ILTV, aMPV is a recent discovery, first seen in South Africa in 1979, and the following year in Europe and the Middle East (as so-called Swollen Head Syndrome'), said Professor Jones. Two types were initially identified: A and B, until a third type (C) was detected in the US in 1996. So far, the virus has not yet been found in Australia or Canada. Its origin and method of spread are not yet understood.

aMP is mainly a disease of turkeys, where it most often causes a drop in egg production, or runny eyes and nose. Occasionally, swollen head is seen. Good control can be achieved by attenuated live vaccines, which contain sub-types A or B, given early in life as a spray. The sub-types A and B offer good cross-protection.

It has been confirmed, however, that reversion occurs in turkeys, making the need for a stable vaccine especially important. Professor Jones said that a reverse genetics system is showing positive results. New evidence from Italy suggests that the previously effective older vaccines offer less protection against newer isolates.

Infectious Bronchitis Virus (IBV)

IBV is the most important viral disease of poultry, explained Professor Jones, in those countries unaffected by avian influenza and the most virulent form of Newcastle disease. Losses in the UK alone amount to £24 million.

First reported in 1931, IBV is a type III coronavirus. The virus causes a number of disease syndromes, primarily respiratory symptoms in all ages and types of poultry. It may affect reproduction in laying hens, causing reduced egg production and quality problems – as well as nephritis in young birds and possibly also enteric and fertility problems. The virus is found in the trachea, gut and oviduct.

There are many different genotypes of IBV, and new ones are constantly emerging. The Massachusetts type is the one universally used in vaccines. Professor Jones went on to explain the origins of the IBV variants, which form as the result of changes in the spike gene following RNA mutations and/or recombinations.

It is the formation of new variants that makes the control of IBV most challenging: thankfully, they appear rarely but this seems to be becoming more frequent, said Professor Jones. Not all new variants require a new vaccine, he stressed.

Turning to his surveillance data of the variants in Europe over the last five years, Professor Jones showed that the 793B and Massachusetts types have been the most prevalent. Italy 02 seems to be falling and it is well controlled with existing vaccines. However,the QX type is causing concern. It was first detected in China in 1998 and in Europe in 2003. Its prevalence is increasing, causing nephritis and 'false layers'. Vaccines against QX are in development although so far, good control has been achieved using existing vaccines, alone or in combination.

Professor Jones commented that the spread of IBV is similar to that of highly pathogenic avian influenza although without the apparent involvement of wild birds.

Professor Jones said that IBV is controlled well with homologous vaccines. However, new variants continue to challenge vaccine strategies, and continuous surveillance is essential. The use of vaccine combinations are effective in many cases, and there are questions over the cost-effectiveness and acceptability of new molecular vaccines.

Conclusions

Professor Jones returned to this original question as he summed up his presentation, saying that none of these three diseases – ILT, aMPV or IBV – is satisfactorily controlled. Despite the widespread use of vaccines, there is still much field virus. Improved vaccines are required that are effective, and produce neither reversion nor latency.

One of the biggest challenges is the evolution of these viruses through mutation, recombination, and changes in tropism or species. The issue is further complicated by wild bird reservoirs and global movements. IBV is a special problem, Professor Jones said, because the new variants always seem to be one step ahead.

Professor Jones is a member of the Department of Veterinary Pathology at the University of Liverpool. He has dedicated much of his career to poultry veterinary medicine, and his principle interests include avian reoviruses and the three respiratory viruses covered in his presentation. Professor Jones was awarded a personal chair at Liverpool University in 2004.

Dr Robert Fraser Gordon set up the UK's Animal Health Trust, a research station dedicated to the study of poultry diseases, in 1948. He achieved both national and international recognition for his contributions to our knowledge of poultry health.

To commemorate his life and work, the Robert Fraser Gordon Memorial Trust was established in 1982, the year after his death. Among its functions is the selection of one person each year who has made a distinguished contribution to a branch of poultry science. One of the trustees is Professor Peter Biggs, who presented the medal to Professor Jones following his lecture.

April 2009