Coccidiosis Specialist Offers Tips for Sustainable Rotation Programs

US - A combination of good management coupled with the adoption of innovative programs should make it possible to achieve long-term, sustainable coccidiosis control, according to Dr David Chapman in 'Poultry Health Today' from Zoetis.As long as chickens are raised on litter, coccidiosis will remain a threat to the poultry industry, according to H. David Chapman, PhD, a coccidiosis specialist at the University of Arkansas.

"Currently, the only tools we have to control this disease are anticoccidial drugs and a few vaccines," he says in an exclusive article written for Poultry Health Today. "However, a combination of good management coupled with the adoption of [innovative] programs ... should make it possible to achieve long-term, sustainable coccidiosis control."

Coccidiosis is an intestinal infection of chickens caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Eimeria. The disease has caused catastrophic losses worldwide and in the US alone, costs poultry producers an estimated $600 million annually, Dr Chapman explained.

Astute poultry growers will recognize coccidiosis when the birds appear depressed, have ruffled feathers and stop eating and drinking. Poor weight gain and feed conversion occur. In some cases and depending on the Eimeria species involved, mortality may be significantly elevated.

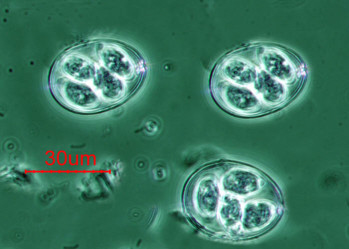

Eradication of coccidia has proved impossible and the transmission stage of the parasite – known as oocysts – can be found in the litter of most commercial broiler houses (Figure 1).

Coccidia have also proved to be supremely adaptable; when the same in-feed anticoccidial drug is continuously used, the result has been the development of Eimeria strains that are no longer responsive to the medication.1

Fortunately, good control of coccidiosis is possible thanks to the availability of many effective drugs and the introduction of coccidiosis vaccines. In addition, innovative programs have been introduced that can overcome the problem of reduced Eimeria sensitivity to in-feed anticoccidials.

Ionophores versus synthetics

Anticoccidial drugs fall into two broad categories: the ionophores and the synthetic drugs (popularly known as chemicals). Ionophores are produced by fermentation, whereas chemicals are produced by chemical synthesis. Examples of ionophores include lasalocid, monensin, narasin and salinomycin. Examples of chemicals include amprolium, decoquinate, nicarbazin and robenidine.

It has been shown that these drugs inhibit parasite development, but in most cases they are no longer completely effective due to the acquisition of drug resistance. However, a sufficient number of parasites often escape drug action and stimulate an immune response in the bird.2 This development of immunity has important practical consequences since it may allow the drug to be withdrawn from the feed well before the birds are sent to market, resulting in a much reduced risk of drug residues in poultry meat and a considerable reduction in medication costs.

Shuttle and rotation programmes

In general, ionophores have a similar mechanism of action against the parasite, whereas chemicals have different modes of action; therefore, a strain that develops resistance to an ionophore may be controlled by a chemical, and vice versa. The poultry industry has taken advantage of this with the introduction of shuttle and rotation programs that have helped slow the development of resistance.

A shuttle program involves utilizing a different drug in different feeds provided to the growing chick. For example, one frequently employed shuttle program involves the use of nicarbazin in the starter feed and an ionophore in the grower diet. A rotation program involves using different drugs in successive flocks.

The underlying assumption behind these programs is that if the parasites develop resistance to one component, they will be eliminated by the other. The majority of poultry producers today use one or both types of program and this has helped achieve sustainable control of coccidiosis.

Coccidiosis vaccines

Live vaccines, such as Inovocox®, Immucox®, Coccivac®-B and others have long been available for the control of coccidiosis in chickens. Coccidiosis vaccines usually contain small numbers of a mixture of important Eimeria species such as E. acervulina, E. maxima and E. tenella that parasitize the duodenum, mid-intestine and ceca of the digestive tract, respectively.

Traditional vaccines are not attenuated and comprise small numbers of oocysts from potentially pathogenic strains of Eimeria. More recently, vaccines comprising attenuated strains have been introduced that have a poor ability to multiply in the bird and are therefore inherently less pathogenic. Nevertheless, they retain immunogenicity. With appropriate management, both types of vaccine can be used to successfully immunize birds against the parasites that cause coccidiosis.

Vaccination used to be restricted to egg-laying stock, but its use in broilers has been facilitated by the introduction of improved application such as edible gels in chick trays, spray cabinets and inoculation of the developing embryo with live oocysts (in ovo administration).3

Restoring drug efficacy

One of the most significant contributions to improved control of coccidiosis has been the finding that the problem of drug resistance can be ameliorated and the efficacy of an ionophore restored when it is administered after the use of a vaccine comprised of Eimeria strains that are still sensitive to ionophores.4 This was first demonstrated for monensin and subsequently for salinomycin.

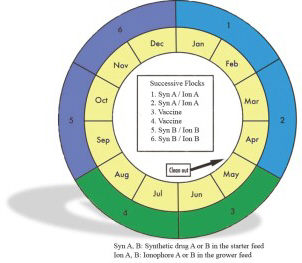

An example of an annual rotation program that incorporates in-feed anticoccidials and a vaccine for six successive flocks is illustrated in Figure 2.

The first two flocks are reared using a shuttle program involving a synthetic drug in the starter, followed by an ionophore in the grower. This is followed by two flocks that are vaccinated, then two flocks that receive a shuttle program involving a different synthetic drug in the starter and a different class of ionophore in the grower feed.

Ideally, a clean-out should follow the first two flocks to help reduce the numbers of any drug-resistant parasites that may be present. The drug-sensitive vaccine strains will repopulate the poultry house when the vaccine is employed, which helps improve the efficacy of in-feed anticoccidials in subsequent flocks.

Many variations of this basic concept are possible and indeed used by the poultry industry. In the US, vaccination is often carried out in the summer months following a clean-out in spring and various drug programs are used during the rest of the year when the challenge from Eimeria parasites is often the greatest.

As long as chickens are raised on litter, coccidiosis will remain a threat to the poultry industry. Currently, the only tools we have to control this disease are anticoccidial drugs and a few vaccines. However, a combination of good management coupled with the adoption of the programs described above should make it possible to achieve long-term, sustainable coccidiosis control.

Dr. Chapman is a parasitologist specializing in the study of coccidiosis. He joined the Center of Excellence for Poultry Science at the University of Arkansas in 1990, where he initiated a coccidiosis-control research program. Chapman has published numerous papers on coccidiosis and is widely recognized as an authority in his field.