Rennier: NAE programs represented 40% of US broiler feeds in 2017

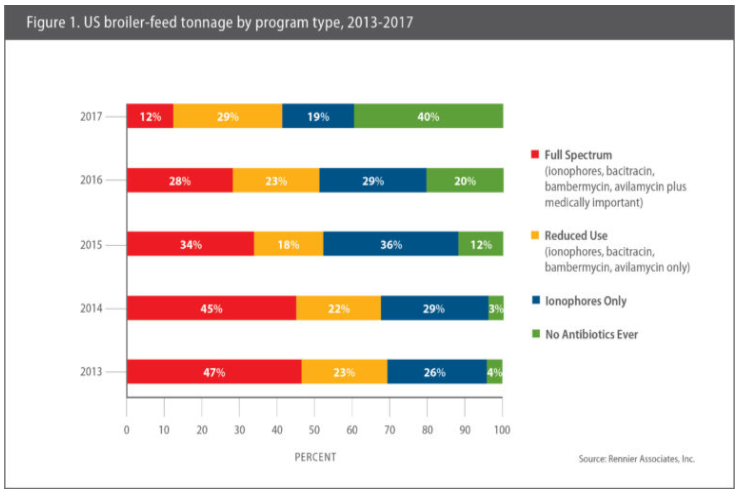

Chickens raised without antibiotics of any type consumed 40% of the broiler feed produced in the US in 2017, according to Greg Rennier, PhD, president of Rennier Associates Inc. Columbia, Mo., a firm that tracks poultry-health trends.That was double the feed tonnage for No Antibiotics Ever (NAE) programs produced in 2016 and a 10-fold increase from 4% 5 years earlier.

At the other extreme, feeds produced for what Rennier calls Full Spectrum programs — that is, production systems that keep the door open to using any FDA-approved antibiotics for poultry, as needed — dropped to 12%. That’s less than half the Full Spectrum tonnage produced in 2016 and a little more than 25% of what the US broiler industry produced in 2013. (Figure 1.)

‘Huge hit’

‘Huge hit’

“Full Spectrum programs took a huge hit in 2017 — and that’s a big part of the story,” Rennier told Poultry Health Today in an exclusive interview. “It’s not just about the NAE feed doubling in one year; it’s watching Full Spectrum fall from 28% to 12%. That’s a big drop.”

The decline in Full Spectrum programs was driven largely by the FDA Industry Guidance 213, which removed performance claims from antibiotics such as virginiamycin, which FDA considers medically important to humans.

Therapeutic usage of another medically important antibiotic, tylosin, which belongs to the macrolide family used in human medicine, was discontinued after its primary sponsor voluntarily withdrew poultry claims from its in-feed formulation, Rennier said.

Middle ground

In between, there are signs the US broiler industry may be finding middle ground. For example, feed that was for what Rennier calls Reduced Use programs — those that produced only with antibiotics not considered medically important (ionophores, bacitracin, bambermycin and avilamycin) — accounted for 29% of the broiler feed, up from 18% 2 years earlier.

At the same time, Rennier noted, feed produced under World Health Organization (WHO) antibiotic guidelines — specifically, those containing ionophores and no other antibiotics — accounted for 19% of the broiler-feed tonnage, a little more than half the level used in 2015. This decline reflects the surge in NAE feeds, he said.

“For many integrators, switching to NAE meant dropping the ionophores and switching to the synthetics (non-ionophore anticoccidials) for coccidiosis,” Rennier said. “So, we saw a decline in our Ionophores Only category. Ionophores are still being used, but more so by either companies on Reduced Use programs with other non-medically important antibiotics and those on Full Spectrum programs.”

Two types of NIAs

While it is not broken down this way in his report, Rennier puts the non-ionophore anticoccidials, or NIAs, into two categories — the “annuals,” which are those used seasonally every year without noticeable resistance buildup, and other, less stable medications that can be “used once and then you stay away from them for 5 years.”

“There are more ‘annual’ products available now,” he said, so resistance buildup is less of a concern than it was years ago when some non-ionophore anticoccidials burned out quickly after continuous use.

Despite the decline in usage of ionophores, Rennier thinks the trend is probably short lived.

“At some point the ionophores will come back because there’s not a lot of tools left in the toolbox,” he added. “It’s just that now, it seems NIAs are what some poultry companies are testing to see how successful they can be with a NAE program.”

“I think ionophores will always be part of the mix [for coccidiosis management]” Rennier said. “But right now, people are trying to play with these NAE programs. Some integrators have successfully run the non-ionophore anticoccidials for years, so dropping them was the easiest way to get there.”

Will NAE plateau?

Rennier noted that while NAE was clearly the fastest growing feed category over the past five years, he thinks that segment of the market will plateau over the next year or two — probably somewhere between 45% and 60%. He cited two reasons.

First, in 2016, Rennier said there are big spike in NAE feed production in the last quarter of the year, a trend that continued in 2017. “We did not see the same pattern at the end of the 2017, which suggests more stability — a leveling out of the NAE trend,” he said.

He also pointed to a report by Sanderson Farms, the US poultry’s industry’s third largest producer, in January 2018 showing that that while 40.5% of the broilers were on NAE programs, only 6.4% of the poultry meat was marketed as NAE.1 While breast meat and whole chickens marketed as NAE command steep premiums — legs, wings and other parts are not sold with the NAE label.

The weekly USDA National Retail Report of chicken prices reflects that trend. For the week ending April 20, 2018, boneless, skinless chicken breast from what USDA calls “specialty birds” — those raised on an all-vegetable diet and without antibiotics — averaged $4.82 a pound, nearly than twice the $2.47 a pound charged for the same cut (regular pack) from conventionally raised broilers. NAE whole fryers sold for $1.82 a pound compared to $1.01 for bagged fryers from other birds.2

Interestingly, however, consumer prices level out for chicken parts. During the same period, for example, whole wings and leg quarters (tray packs) for NAE birds were comparably priced — averaging $2.41 and $0.81 a pound compared to $2.35 and $0.86, respectively, for conventionally raised birds.3

“I think some producers are looking at that and concluding there’s no reason to go to the expense of raising birds without antibiotics and then selling them as conventional,” Rennier said.

The other big shift in feed additives can be seen in alternative products — prebiotics, probiotics, oils and botanicals, for example —used to help manage disease.

According to Rennier, 2017 was a watershed year for these products, outselling medicated feed additives. Poultry companies are also using multiple additives in the same ration, not just one or two as they might with traditional feed medications.

“I would say the market for direct-fed microbials has and probably will continue to surpass that of antibiotics for the foreseeable future,” he added.

References:

1. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-sanderson-farms-chicken-antibiotics/u-s-faces-oversupply-of-antibiotic-free-chicken-sanderson-farms-idUSKBN1F6021

2. https://www.ams.usda.gov/mnreports/pywretailchicken.pdf

3. Ibid.