More than half of US broilers raised without antibiotics in 2018

Up from 3 percent in 2014, the trend is set to stabilise.Broilers raised without antibiotics accounted for 51 percent of total US production in 2018 - an 11-point jump from the previous year and, more significantly, up from 3 percent in 2014.

“Over the past 5 years, this market has changed tremendously,” Greg Rennier, PhD, president of Rennier Associates Inc, Columbia, Missouri, a firm that tracks poultry-health trends, told Poultry Health Today.

He doesn’t expect that number to go much higher, though. “My guess is it could reach 60 percent over the next year or two and then stabilise,” the veteran trendwatcher predicted.

“There’s always going to be a part of the market that will use ionophores,” he added, referring to a class of animal-only antibiotics commonly used to prevent coccidiosis, a major intestinal disease of poultry. “Others will need to use an antibiotic to keep necrotic enteritis (NE) in check. Those two diseases aren’t going away.”

In fact, in his interviews, US poultry companies listed NE as the number one disease concern in broilers in 2018, followed by coccidiosis. “Those two have been the top two disease concerns over the past 5 years - basically, since the trend started toward raising poultry without antibiotics,” Rennier said.

Filling the void

What are poultry companies using to fill the void?

So far, no antibiotic alternatives have provided consistent control of NE. However, there are several dependable options for managing coccidiosis, which in turn helps to prevent or reduce the impact of NE.

Rennier said the most widely used feed medications in No Antibiotics Ever (NAE) production systems are non-ionophore anticoccidials (NIAs), which include nicarbazin, which is typically used in the winter months only, and zoalene, a feed medication that was reintroduced in 2014 after being out of production for 9 years.

“Nicarbazin use has stayed at about the same level for the last 5 or 6 years, where zoalene has really taken off and become the US poultry industry’s leading feed medication,” Rennier said.

What’s unique about both NIAs is they “don’t kill 100 percent of the bug,” which he said is a good thing. “In the past, some of the NIAs would totally decimate the coccidia population and left only super-resistant bugs behind. From what I’ve learned in my interviews, zoalene and nicarbazin don’t work that way; they walk that balance well between protection but not overprotection.”

Vaccine trends

Coccidiosis vaccines have also become standbys in NAE production schemes. In 2018, they were used in 36 percent of flocks, down from 41 percent the previous year but still holding strong. “And I think that’s about where they’re going to stay - about slightly more than one-third or more of the broilers getting the vaccine,” Rennier said.

“Vaccines can be effective, but they take a lot more management. Poultry companies realise vaccines need to be part of the rotation and may help extend the effectiveness of the feed products.”

In recent years, he added, vaccines have also been used as part of so-called bioshuttle programmes, where an in-feed anticoccidial is used after the live vaccine’s oocysts have completed two cycles.

While more and more birds are being raised without antibiotics, industry statistics show that 7-day mortality rates have surged to about 1.5 percent or higher, regardless of whether birds are raised NAE or with antibiotics in their feed. That’s twice as high as it was a few years earlier - a trend veterinarians attribute to the decline in antibiotic use in the hatchery. Rennier said only 16 percent of birds receive an antibiotic in the hatchery, down from about 90 percent in 2013.

“It’s just a different environment when you remove the crutches or helpers that have been used in the past. It’s going to take the market a while to adjust to that,” he said.

Beyond NAE

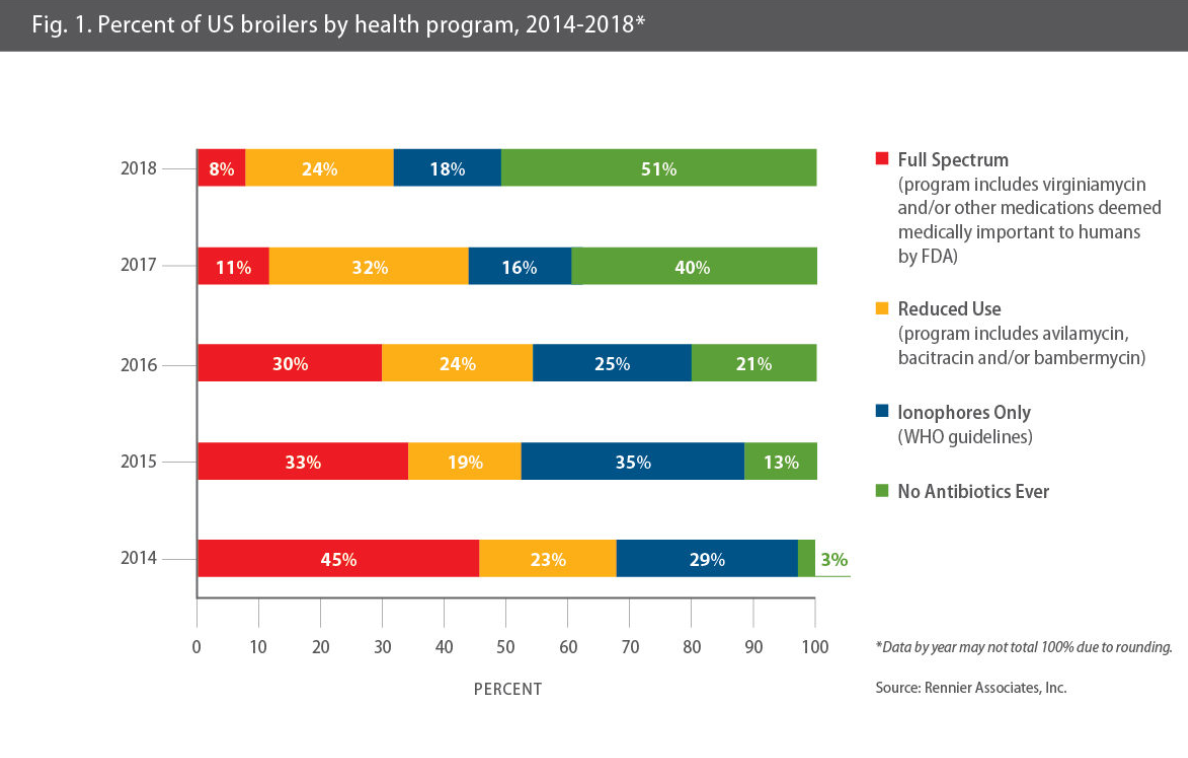

Despite all the attention given to NAE production, Rennier said, it’s important to remember that half of the broilers produced in the US still get some type of antibiotic to prevent, control or treat disease. He breaks these flocks into three categories - Full Spectrum, Reduced Use and Ionophores Only.

Flocks in the Full Spectrum category are those raised with any feed antibiotics approved by the FDA, including responsible use of those classified as medically important to humans. According to Rennier, only 8 percent of broilers were raised in Full Spectrum programmes, down from 11 percent in 2017 and a fall from 45 percent in 2014 (Fig. 1).

“And my guess is that it’s going to go even lower - perhaps to only 4 percent to 5 percent of flocks - because a major US integrator recently announced that they were eliminating human-grade antibiotics,” he said. “Most of that is virginiamycin (used for preventing NE).”

Animal-specific antibiotics

The next tier is Reduced Use, which means using feed antibiotics not deemed medically important to humans. For US poultry companies, that translates to production schemes that include bacitracin, bambermycin, which may be used without a veterinary feed directive, and/or avilamycin. This group accounted for 24 percent of US broilers during 2018, down from 32 percent in 2017 but up from a 5-year low of 19 percent in 2015 (Fig. 1).

Rennier attributed these fluctuations to “people playing with programmes between 2014 and 2017 - seeing what they could do with and without.” While he expects this category to dip a few more points in 2019, he also thinks it will stabilise. “The industry’s experimentation phase is coming to an end. People are getting more comfortable with their choices and patterns,” he added.

The fourth category of antibiotic usage is Ionophores Only. As its name implies, this refers to broiler chickens that received one type of antibiotic - ionophores - which may be used under World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines. Rennier said this group accounted for 18 percent of US broiler production during 2018 (Fig. 1), which he said was down from 5-year high of 36 percent in 2015.

Ionophores are unique in that they’re classified as antibiotics in the US but not in Europe and most other poultry markets. “You don’t see the US market making much of a push to reclassify ionophores outside of the antibiotic category, like WHO does,” Rennier said. “So, without someone leading that fight, ionophores are still going to be looked at as an antibiotic in the US - and I think the general downward trend [in usage] is going to continue.”

DFM market exploding

Rennier also looked at eubiotics – direct-fed microbials (DFMs), botanicals, organic acids and yeast, to name a few. “This market has exploded in recent years,” he said.

Usage trends in 2018 are proprietary, so he could not share details with Poultry Health Today. “What I can say, in general terms, is that eubiotics are now in twice the amount of feed that antibiotics are - up from basically nothing a few years ago,” Rennier continued.

“I’ve seen as many as four of these antibiotic alternatives in a single feed ration” he added.

Why NAE in the first place?

The changes in poultry antibiotic usage over the past 5 years have been nothing short of remarkable, but what specifically is driving the trend? Are consumers that concerned about antibiotic usage that they’re willing to pay, according to USDA’s May 3, 2019, report, $3.93 per pound for “specialty” skinless/boneless chicken breast (which includes birds raised without antibiotics) instead of $2.26 (value pack) for the same cut from conventionally raised broilers?1 Or are other forces at work?

Rennier thinks most US poultry companies simply don’t want to discuss antibiotics with their customers.

“If a big customer asks about antibiotics, the integrator prefers to say, ‘We don’t use any,’ ending that difficult conversation. But if they say, ‘Yeah, we’re using some here and there,’ it becomes a long, drawn-out discussion. For them, the simple answer is ‘no’.”

Nevertheless, it’s important to note that the premium price for NAE chicken has softened as more of NAE product has come on to the market. While boneless chicken breasts from conventionally raised birds has remained relatively flat over the past year ($2.26 vs. $2.24 the same week last year), the current $3.93 price for the same cut from NAE birds is down 16.7 percent from last year’s average price of $4.72, according to USDA’s May 3 report.