Shielding Layers from Infectious Bronchitis

UK producers tap the power of existing vaccines to guard layer flocks against costly variants of infectious bronchitis (IB), according to Joseph Feeks in the Journal of Poultry Respiratory Protection from Merck Animal Health, US.Between the spread of the QX variant of infectious bronchitis (IB) and the constant threat of other strains, one might expect the UK layer industry to be reeling from false layer syndrome, poor egg quality and other costly side effects linked to this evolving disease.

As it turns out, however, leading producers there are not only coping with emerging IB variants, they’re actually seeing gains in production — even in free-range birds that now dominate the national flock.

PRP’s managing editor, Joseph Feeks, visited the UK headquarters of Hy-Line, the world's leading supplier of layer breeders and day-old laying stock, and Country Fresh Pullets, the UK's top layer-pullet rearer, to see how they were faring in the face of dynamic IB variants.

Experience at Hy–Line UK

With up to 50,000 grandparent (GP) layer breeders and 142,500 parents on Hy-Line’s floors at any one time, UK breeder farms manager, Richard Beevis, cannot afford any hiccups in production. Keeping birds healthy and growing at a desired rate and uniformity are essential to the success of his operation.

There is also plenty of peer pressure – literally. Internal peer reports at Hy-Line compare his production efficiency against other company farms in France, Brazil and North America. “That keeps us motivated,” says Mr Beevis, who is based at the company’s facility in Studley, Warwickshire.

For Mr Beevis, the critical milestones in his operation are seven–day mortality, as well as the bodyweight and uniformity at six and 12 weeks.

“We’re typically targeting at least 80 per cent uniformity,” he says. “We also try to get the bodyweight up at 12 weeks – about 100 grams higher than target – because they naturally go through a five per cent to 12 per cent weight loss when we move them from small colonies of 1,500 to 2,000 to colonies with 5,500.”

While Mr Beevis and his veterinary consultant, Paul McMullin, MRCVS, need to keep their eyes on several intestinal and respiratory diseases in the GPs and parents, IB commands the most attention.

“There’s no question, we’re more conscious of IB than any other disease,” Mr Beevis adds. “If left uncontrolled, IB could have a devastating impact on our operation. Fortunately, we’ve managed to stay a few steps ahead of the disease.”

* "We’re more conscious of IB than any other disease" |

Not just respiratory disease

When asked about the prevalence of IB, Mr McMullin initially describes the disease as the “chicken version of the common cold because, in essence, it will always be there in one form or another. There’s also a wide variety of strains, some more aggressive than others.”

But his common–cold analogy quickly ends there. “The trouble there is, comparing IB to a cold implies that IB is an upper respiratory problem, which it can be, but IB is able to infect a broad range of tissues," says Mr McMullin, who has worked with the disease for 25 years in Brazil, Europe and Africa.

"In fact, the area where we can most readily demonstrate the presence of IB viruses for long periods after challenge is actually in the digestive tract, particularly those that are clustered in what is called the caecal tonsil. Kidneys can also be affected, as well as, of course, the reproductive tract. Calling the disease infectious bronchitis really is not giving it credit for everything that it can do.”

Uniform eggs essential

Not surprisingly, the biggest concern at an operation like Hy-Line – or at least where the effect of IB is most visible – is its potential impact on egg production. “If we were running tight on eggs and suddenly had a large farm with a five per cent or eight per cent drop in production from IB – eggs that we were counting on to set for our customers – that would be a big problem for us,” Mr Beevis says.

Furthermore, the eggs that are produced by infected birds are usually poor quality, with thin shells. “We’re very strict in our criteria for selecting hatching eggs – an absolute minimum of 53 grams – so we can’t afford to have something like IB compromise our standards or chick quality,” Mr Beevis says.

“With bronchitis,” he adds, “it’s not just the period of time that layer operations might see any production drop. It’s prior to the drop and post the drop as well. The egg drop might last only a couple of weeks, but IB could actually affect about eight weeks of physical production – two or three weeks before the drop and another two or three weeks after the drop.”

| * "The egg drop might last only a couple of weeks but IB could actually affect about eight weeks of physical production." |

|

Richard Beevis

|

Fortunately, Mr Beevis says, they have yet to have a positive diagnosis for IB on any of their farms but that does not mean it has not knocked on his door. According to Mr McMullin, Hy-Line’s strategic approach to IB vaccination is designed to protect against a broad range of variants including the costly QX variant, which can attack the kidneys and central nervous systems of birds.

Broader protection

Hy-Line’s success managing IB is a good example of the phenomenon known as Protectotype, he says. “Neither the Ma5 nor the 4/91 on their own provide good immunity for the QX strain but in practice, when they’re used sequentially or sometimes in combination, they have been shown to provide quite good protection,” Mr McMullin adds.

The programme starts on day 1, when chicks are vaccinated at the hatchery with Nobilis IB Ma5 and then at day 14 with Nobilis IB 4/91, both live vaccines. “Up to a couple of years ago, it was quite common to vaccinate broilers at day–old and not so common to vaccinate layers at day–old,” Mr McMullin says. “That has changed, because clearly it's important with this particular QX strain, which is prone to cause damage to the oviduct if it occurs in early life.”

The Ma5 vaccine is used again at 5.5 weeks and 4/91 is repeated at 10 weeks. Birds are vaccinated at transfer – usually at 16 weeks – with Nobilis RT+IB Multi+ND+G (for GPs and breeders) or Nobilis RT+IB Multi+ND+EDS (for parents and pullets), inactivated vaccines that contain two IB serovars, plus avian pneumovirus, Newcastle disease and egg-drop syndrome viruses. At 18 weeks, they resume priming birds with live vaccines every six to eight weeks and into lay.

“Technically, the local immunity achieved by the live vaccines we use in rearing will last up until 20 to 23 weeks of age,” Mr McMullin says. “The problem, though, is that by 20 to 23 weeks, flocks are coming into lay. That is a period of high physiological stress, so it's a very bad time for birds and they’re very susceptible to new infections.

"For that period of increased risk, after giving the inactivated usually on transfer, we generally recommend re-vaccinating with a live vaccine after about seven days – after the flock has settled into the new accommodation, which also has its stresses," the veterinarian adds. "If we can avoid it, we don’t vaccinate for the following 10 weeks or until they are over peak production.”

On-site support

Reflecting on their ability to fight off IB in the face of QX and other variant strains, Mr Beevis says, “The vaccines are doing their job, no doubt about it. We see mild – very mild – IB challenges in most flocks most years. But at the moment, it’s short-lived. IB comes and goes. The QX variant is becoming more prevalent in the UK, yet we haven’t changed our vaccination programme for 12 months. I think that says something about the vaccine products we’re using and when we’re using them.”

Mr Beevis also credits Jonathan Perkins, a sales manager at MSD Animal Health, for the success of their IB management programme. “Jonathan has worked closely with us, providing training and auditing, which have been very useful,” Mr Beevis says. “He’s conducted excellent workshops here for the people that actually handle our inactivated vaccine for us, as well as for the farm managers.

"These workshops keep everybody fresh," Mr Beevis continues. "If people understand why they’re doing something, they’ll do a better job. If they understand the consequences on a rearing farm as to why they need to administer an IB spray vaccination correctly, and if they understand the consequences of what happens if they don’t perhaps toe the line, then they’ll focus more.”

Experience at Country Fresh Pullets

While consistency and uniformity might be the hallmarks of a layer–breeder producer, diversity and customisation are the bywords at an operation like Country Fresh Pullets, Shropshire – the largest pullet rearer in the UK.

“We are totally customer–driven,” says Richard Parsons, production manager. “We don’t advertise breeds. Whatever the customer wants, we will rear. We’ve got the space. Last year, we reared in excess of seven million.”

Country Fresh currently rears layers from Hy-Line, Lohmann, Goldline, Hendrix Genetics and at least five other breeding companies. “We also do some Columbia Blacktails. And we also do a few what we call specials – exotic things that lay blue eggs and brown eggs.”

Country Fresh has 34 contract and 15 company–owned farms ranging in capacity from 6,000 to 200,000 birds. Farms take delivery of day–old chicks and then rear them to week 16. During that time, birds are typically primed and boosted with vaccines 16 or 17 times, against a wide assortment of poultry diseases.

* "We have to provide a bird that’s been given the maximum IB protection available" |

‘Massive concern’

“Obviously, vaccination is critical to our own production, but it’s even more critical to the end-user, our customer,” Mr Parsons says. “We want repeat customers. So it’s important that our product leaves us with the highest level of protection possible.”

Mr Parsons lists Marek’s and Gumboro as the most feared diseases in their rearing operations but his radar is firmly fixed on IB and its changing variants.

“We don’t tend to see too many IBs in a rearing environment. It’s not something that would affect us here today,” he says. “But obviously, for our customers, it’s critical that the birds are protected because there’s a lot of bronchitis out there. If our birds get an early infection with an IB QX, for instance, then the repercussions to the lay of our customer could be severe. So basically, if IB is a concern for them, it’s a massive concern for us. We have to provide a bird that’s been given the maximum IB protection available.”

For that reason, Mr Parsons continues, they were advised last year to introduce Nobilis IB Ma5 at day–old, which is administered in the hatchery, and then follow up with Nobilis IB 4/91 at 14 days, both live vaccines.

“Our vets, as well as the veterinary surgeons of our customers, tell us that’s the best cross-protection available against QX, which can be devastating in the laying environment,” Mr Parsons reports. “And theoretically, they also cross-protect against IB 755 (Italian 02) and other variants. The tricky thing is, the variants change all the time. You never know what to expect. We do serology at 12 or 13 weeks to make sure the priming vaccines are doing their job. But in general, the vast number of IBs that we’re seeing are related to 793B (of the same Protectotype as 4/91) or QX."

No standard programme

| * "Birds like routine; they love routine. But when you put birds into a free–range situation, routine is blown out of the water." |

|

Richard Parsons

|

The Ma5 vaccine is administered again at day 35, this time as Nobilis Ma5+ Clone ND, which includes protection against Newcastle disease, followed by another IB primer vaccine at day 84 to protect against the IB H120 and IB D274 variants. At transfer, birds are vaccinated with the inactivated combination vaccine Nobilis RT+IB Multi+ND+EDS “for extra IB barriers.”

“We’ve got something like 67 vaccination programmes currently in our database that we use all the time,” Mr Parsons says. “There’s no such thing as a standard programme but broad IB protection is something our customers need to have.”

When Mr Parsons joined Country Fresh 21 years ago, the company predominately used one breed of bird. "They pretty much received all of the same vaccines and that was it,” he recalls. “Now, we have about 10 different breeds out there, all of which will be transferred to different types of farms, in different environments with different lighting and so on. We have to segregate houses by breeds, lighting and vaccination programmes.”

More than anything, Mr Parsons says, the industry’s switch to free-range production – now practised by about 70 per cent of his customers – has increased flock exposure to diseases.

‘Blown out of the water’

“When birds were in cages, they were in a controlled environment and probably subjected to less stress,” he says. “Birds like routine; they love routine. But when you put birds into a free–range situation, routine is blown out of the water. Birds are being let outside so they’re exposed to more disease – not just the IBs but farm–specific problems. If people are raising pigs and sheep in the range area, for example, erysipelas and E. coli can be a concern. The demand for more complex vaccination programmes is being driven by free–range.”

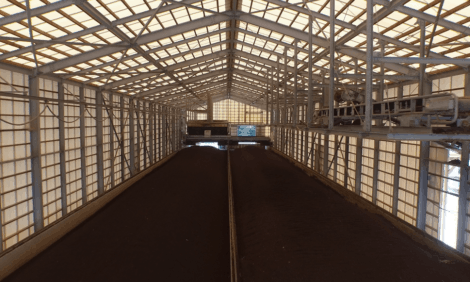

To minimise stress on its birds, Country Fresh works under two auditing bodies – Freedom Food, the farm assurance and labelling initiative monitored by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA), and the British Lion Code of Practice administered by the British Egg Industry Council. Many of their farms now have slatted–perch flooring areas, which helps maximise production per square metre while allowing birds to be more mobile and develop better leg strength, Mr Parsons says.

“That's a huge advantage for the free-range layer,” he adds. “The stronger the bird is, the better it will withstand the rigors of IB and other disease challenges.”

Further Reading

| |

- | Find out more information on infectious bronchitis by clicking here. |

March 2012